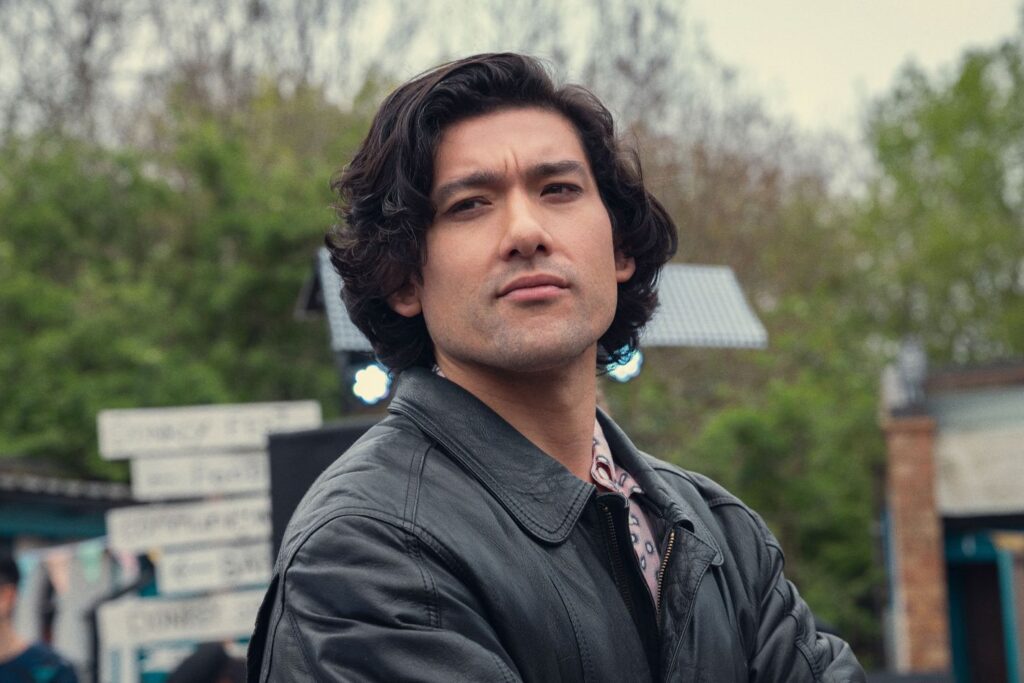

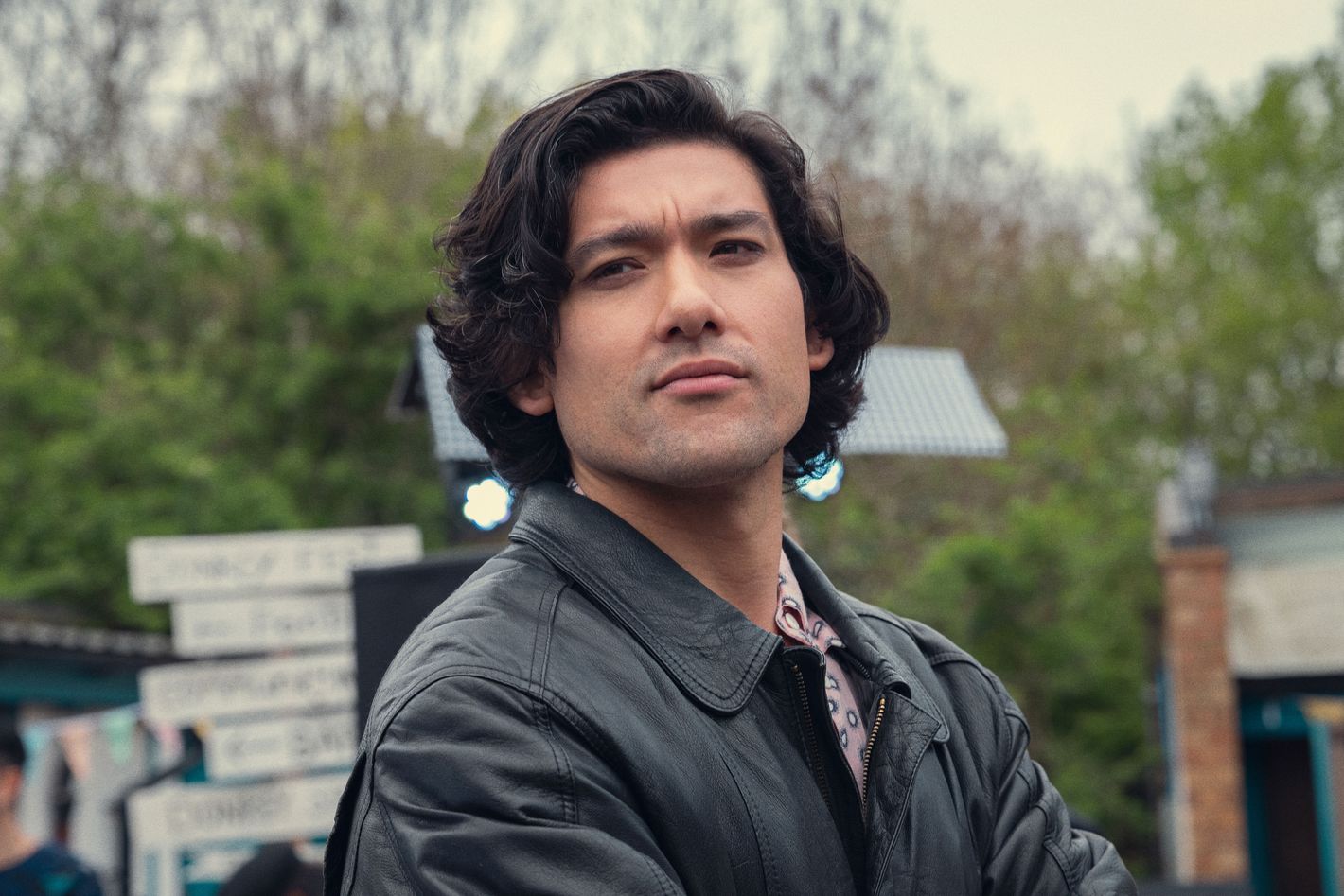

In my recap for the previous episode, I expressed a wish that we’d get deeper into Felix’s reasons for not being able to say he loves Jess. In every other respect, Felix is communicative; he hasn’t shied away from telling Jess honest truths or from making his affection known. He’s kind toward her, attuned to her moods and needs, and happy not only to appease but to appreciate her eccentricities. There’s a touch of Nice Guy Syndrome to him, as we’ve discussed; all of this together points to a guy who should be very used to telling someone he loves them. What could possibly be going on?

The answer, as it so often does, has to do with parents. Coming back from a day spent with his family in the suburbs, Felix agrees to tell Jess why the visit has put him in a bad mood, but he warns that once he tells her, there’s no unsaying it. In other words, once this other side of him has been revealed — the part of him that he buries, so that the surface can remain undisturbed — the fantasy is, for all intents and purposes, ruptured. As long as he is a nice guy with no history, Jess can interpret him however she likes; he can be, like Wendy, an abstraction, a person who only exists in service of her emotional needs. That may well suit some of Jess’s moods, and it’s the kind of infatuation that can sometimes characterize the rebound. Having been wounded by Zev’s cruelty, it would be an anesthetic to be loved by someone who exists only to love her. Being a ghost with no baggage would suit some of Felix’s own moods, too: it would give him the opportunity to detach from the prickly, insistent influence of the past.

That’s the risk involved in being vulnerably in love: We excavate our buried parts and hope our lovers will want to forge ahead. That’s the stage at which Felix has always gotten stumped; for a long time, as Auggie told us, he hasn’t been able to dispel the fantasy. That kind of trouble, we learn in “Terms of Resentment,” is inherited: His parents are beholden to fantasies, too. Only they are unable to let go of what their life used to be before they lost a large enough portion of their fortune that Felix’s father, Simon, has to borrow £1,000 from his son.

We’d already gotten a hint that something had gone down in Felix’s family when, fighting with Jonno in his Notting Hill townhouse, we learned that Felix had to leave boarding school because his father had run out of money. As “Terms of Resentment” opens, Jess asks to tag along with Felix for the visit to his family, hoping she can get a glimpse of their gorgeous old house, the kind of grand estate she went to England to see. Felix tells her it’s not a good day for her to meet the parents; he has “stuff to sort out,” and besides, meeting a boyfriend’s family is more a “be invited” than “invite yourself” kind of thing. It’s evident from this interaction that at least part of the reason why Felix doesn’t want Jessica to come is that there’s no way his parents still live in that house.

On the way to the suburbs, Felix trades his nice BMW for a shittier car and makes £1,000 for the difference. Once he’s there, he waits 40 minutes for his mother, Aiko, to pick him up from the station. She would stand to make a little money if only she were to sell her car, a Rolls-Royce, but it soon becomes obvious that Aiko doesn’t want to let go of anything that reminds her of the life she used to have. In the car, Felix shows Aiko a picture of Jessica and Astrid, for whose health she worries. Aiko is funny in an erratic, sad way — she drives the Rolls crazily, smokes constantly out the window, and insists that Felix’s father, Simon, will be able to “get them out of this,” referring to their lost fortune. Felix tells her that they might be able to enjoy their new lives if they accept that it’s too late to make all of that money back: It’s been 14 years since they’ve lived in their old house.

But Aiko is convinced that Simon will eventually buy it back. She stops by the house on their way in from the station. Jess is right: The place looks like it could be Pemberley. Aiko tells Felix that she checks on it every day, and that whoever owns it now usually leaves the doors unlocked. She encourages Felix to go inside while she smokes a joint. He hesitates at first but decides to go in. The house is empty — whoever bought it doesn’t seem to live there, either — and as Felix walks through the rooms, he remembers scenes from his childhood, following the presence of his kid-self around.

Both of his parents were artists; his mother was a painter, and his father — though we never learn what he did for a job or how he was able to amass a fortune coming from a Hungarian immigrant family whose patriarch delivered milk to make ends meet — was a piano player. They were often either absent or inscrutable. They kept a distance from each other as much as they did the children: His dad complains of Aiko “running away with Leland Fellows,” and his mother, stewing in the bath, tells him she’s off to her own world, since Simon is locked away in his. Felix remembers being reprimanded for not doing well in school; his sister’s affection for him; and being left alone with a fever and a nanny who makes him tell her that he loves her, because she’s the one who feeds, clothes, and cares for him. His young self seems bewildered at his own life. The house is like an amusement park, a place full of wonder, but there’s no love to guide him through it.

At least, no kind of love that can instruct and protect; in adulthood, Aiko still refers to Felix as her “favorite playmate.” Over a roast at the much smaller house where they now live — Aiko calls it a “bungalow” — Simon continues to insist they will soon “get out of this.” Aiko says she’d rather die than live in that house, and Felix’s sister, Alaia, ten years older than him, is in arrested development. She kept the butterfly clips that adorned her hair in the ’90s through her 40s, though she’s planning to move out into her friend’s “boiler room” as soon as she finds a job. The Remens’ dynamic is as eccentric as the Salmons’, though their woundedness seems to be less the product of extenuating circumstances than an unwillingness to see things for what they are. Only Felix can manage it: They’re not rich anymore and likely won’t be again. His acceptance of that fact alienates him from the rest of the family, which also drives him crazy.

After dinner, outside, Felix gives his dad the £1,000 he was able to make from selling his car. Simon tells him he plans to use half of it to pay the bills and half of it to start a “payment plan” to buy back the old house, which only shows how delusional he is. Simon tells Felix that in a dream, he remembered something his father used to say to him: “Don’t be a slave to fortune.” That means that each person gets an allotted amount of luck, and once it runs out, there’s no use “hunting for it.” He’s resigned himself to the idea that at one point or another, children are bound to take over for their parents. “We spent what we had on you,” he shrugs. “Now it’s your turn.”

This defeated attitude aggravates Felix so much that, when he leaves the house, he takes his money back with him. When he gets home to Jess — who spent her day watching BBC documentaries and dealing with what her grandmother calls “honeymoon cystitis,” a symptom of “overusing the hardware,” meaning her vagina hurts — at first, he won’t tell her what happened over his visit that made him so sad. Ultimately, though, as she insists — in her very Jess, though caring, way — he opens up. He tells her about his parents’ absence and that the nanny they put in charge of him, whom we saw demanding his love in his memory, molested him. It’s implied that Felix’s paralysis when it comes to saying “I love you” comes from this abuse: She used to make him say it. Felix tells Jess about Aiko’s constant suicidal threats, Alaia’s arrested development, and his father’s maddening self-denial. He tells Jess that as a kid, he was never tucked in.

So, she tucks him in, like a burrito. She sings him the Bob Dylan song her father used to sing for her, and her affection in this moment is so pure, so selfless, that it breaks down one of his staunch barriers. With a tear streaming down his face, he tells her that he loves her. It’s one of those rom-com moments, like when you realize about Allie in The Notebook, in which no matter how much you’ve been resisting the sappiness — no matter how cynically you may regard romance — you just can’t help it. I was moved to tears.

I tend to resent what I perceive as contemporary TV’s over-reliance on flashbacks. As a side effect of the trauma-plot tyranny, it feels like TV is always explaining away its characters, directing our understanding of them to be based on what happened to them before the story started, versus on how they might deal with the events that unfurl as we follow along. Remember that episode of Girls when Jessa and Hannah visit Jessa’s dad in upstate New York? That worked to familiarize us with how Jessa’s family dysfunction affected her in the present, rather than give us a flashback of her childhood to paint a picture of what happened in the past.

“Terms of Resentment” is a version of that episode fitted to Netflix’s more didactic, exposition-heavy style. In Too Much, Dunham has used flashbacks with abandon; they work because they don’t dictate behavior as much as they deepen it. We need to know what went on with Zev in order to care about Jess overcoming it; but because the story is between Jess and Felix, and because Dunham has only ten episodes to work with, she needs to both show us what happened and how it’s affecting the decisions Jess makes with regard to Felix. The same goes for Felix’s family and their fall from grace. The flashback is almost a necessity of the form, rather than a way to substitute character development for character backstory. Applied like this, it’s more novelistic than cinematic; when the telling is good, I don’t mind it overshowing.

We finally get to the bottom of what holds Felix back from being vulnerable in love.