The most shocking aspect of Lena Dunham’s Netflix series, Too Much, is that it looks, well, like a Netflix series. You know the aesthetic, even if you can’t quite name it: brightly lit interiors, dialogue filmed in rapid-cut close-ups, color grading that emphasizes jewel tones and makes your eyes slide off the screen like water on a Teflon pan. These are, perhaps, the specs that Netflix asks from its creators for ease of international distribution, but it’s jarring to see someone with a style as distinctive as Dunham’s force herself into an Emily in Paris–shaped box. On Girls, Dunham and her collaborators depicted the characters’ 20s in what felt like one eternal Brooklyn summer. In Too Much, Megan Stalter’s Jessica Salmon describes her fantasies of life across the pond within other artists’ quotation marks: A little like a period drama, a little like a kooky BBC Three sitcom, a lot like Bridget Jones’s Diary. But later in the series, when Jessica experiences heartbreak or flashes back to difficult memories of her previous life in New York, Dunham reverts to a style of direction that’s all her: a long held shot to punctuate a scene with an ellipsis, moments accompanied by softer lighting and harsher truths. After which, Too Much will revert back to cheerier Netflix mode. Is this a Lena Dunham show smuggled inside a Netflix show, or a Netflix show consuming a Dunham one from the outside in?

That tension may have been baked into the pitch for Too Much from the start, which Dunham has described as both semi-autobiographical and an attempt to re-create the rom-com fantasies of Richard Curtis for the 2020s. After years of intense scrutiny in America about everything she depicted and/or said about Girls or anything else, Dunham found creative solace in Britain, where she directed the pilot episode of Industry and a miraculous adaptation of the medieval YA novel Catherine Called Birdy. She was also set up on a blind date with her now-partner, Luis Felber, a British musician with whom she co-created Too Much. The series takes her journey as the jumping-off point for its central plot: A gregarious girl who is a misfit in America finds herself in an unlikely courtship with a cooler dyspeptic Brit. Jessica is a New Yorker reeling from a breakup with a snooty boyfriend and moves to London for a marketing job, where she meets a reserved musician named Felix Remen (played by The White Lotus season two’s Will Sharpe, a prolific writer and director better known across the pond for movies like the one where Benedict Cumberbatch painted a lot of cats). In the mode of expat escapism, Jessica, who is fond of doing dorky fake Londontown accents, stumbles through various cultural misunderstandings. These are generally easy targets, like an episode that takes place at a snobby house party in Notting Hill and loses steam almost as quickly as it starts. Jessica gets dragged along to an insufferably posh wedding. She meets Rita Ora, who to her credit does a remarkably game parody of herself.

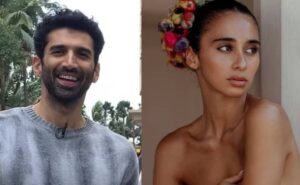

All of this is the stuff of classic romantic fantasy in the vein of Curtis, Darren Starr, and even Jane Austen — at one point, Jessica imagines Felix dressed up as Mr. Darcy — but the whipped-cream portions of Too Much are never as compelling as the glass-shard self-laceration at which Dunham excels. When that mode does make scattershot appearances in the series, it overwhelms it. Jessica’s ex-boyfriend, played by an impeccably scruffy and insufferable Michael Zegen, is a self-important Brooklyn music writer named Zev who has abandoned her for an influencer played by Emily Ratajkowski, also impeccable at being insufferable but in a more serene way. You may already be jumping toward a Deuxmoi-adjacent sub-Reddit to discuss the characters’ obvious similarities to Dunham’s own music-producer ex and his new partner, and Dunham has preemptively insisted Zev is an amalgam of exes. Yet these characters are much more compelling than anyone else on the show.

When Jessica flashes back to memories of her life in New York in episode five, Too Much takes on an energy it lacked in its depiction of London. It’s partially due to Dunham’s abiding artistic interest in putting her hand on the hot pan of controversy about her own self — I can’t believe she included an arc about Jessica’s inability to care for a dog, which is only destined to revive discussions about the saga of Dunham’s dog, Lamby — but more pressingly, she writes about New York and New Yorkers with a biting clarity while depicting London through rose-colored glasses. Though Zev is a total asshole, I wished Too Much would spend more time with him, a textured and real person (he had a Weezer-themed bar mitzvah, delightfully brutal), than with Felix, a dreary and conveniently troubled enigma. The show provides him with a backstory, informed by elements of Felber’s and Sharpe’s own pasts, but it never has the same grip as Jessica’s. He’s a person onto whom her character projects her fantasies, which, as for so many expats, are more about how he represents an absence of the stuff she left behind.

Too Much pushes the notion that both Jessica and Felix must overcome their past traumas for their budding relationship to work, but the spark between Stalter and Sharpe is never so strong as to make all that processing seem worth it. Here, a stickiness in performance also gums up the writing. Stalter is a gifted comedian, and her “I’m doing the joke, but half-heartedly so I know I’m in on it” approach to line delivery can work well in the right circumstances (her viral “Hi gay!” TikTok, for instance). At a safe satirical reserve, Stalter is great and comfortable in Too Much’s broadest comedy (ironically, where the show’s writing is weakest), like when Jessica gets involved in shenanigans at her marketing job. Those scenes on-set with Ora or Andrew Scott, who plays a grumbly director-for-hire, do stand out, even if it’s impossible to believe anyone involved in Too Much has much real experience in being an office drone. But when Stalter has to carry dramatic weight in a scene, she’s tentative, still protecting herself from full vulnerability with a slightly flippant posture.

It’s understandable. Dunham has talked about not wanting to play the lead of Too Much because of the scrutiny she experienced playing Hannah on Girls, and you can imagine how she, as a director, would want to extend some protection around her star. But the fact is that Dunham is an incredible and sensitive dramatic actor, and the scenes where Dunham does appear in Too Much, playing Jessica’s sister and bickering with her gay ex-husband, played by Andrew Rannells, are the liveliest in the show. Dunham’s performance in that crucial scene late in Girls when she and Adam tearfully reunite over soup is up there with the best TV acting of the prestige era, which sets a very high bar for anyone stepping into a similar avatar of Dunham onscreen. Stalter doesn’t achieve that level of depth, nor could many other actors.

Stalter’s reserve as a performer does match a certain reserve in the show’s own aims. In the second episode, Jessica delivers a monologue about how she can’t stand people calling her a “mess,” lashing out at a cavalier footballer who assumes he can get away with insulting her during a group date with her co-workers. It’s a scene that, like many in Too Much, invites a comparison to Girls. The speech is something you could imagine Hannah saying to Adam, another case of her being right in her gender politics but completely wrong when applying them to that specific moment. Here, however, Jessica is overdramatic and killing the vibe but she is, largely and simply, correct in what she’s saying about being called a mess. In keeping with that Netflix smoothness, the show lacks texture — in design, intention, and performance. Too Much is much too neat.

Related

Lena Dunham’s first Netflix series can’t reconcile her autobiography with expat escapism.