In her February Grammy acceptance speech, Chappell Roan called on record labels to “offer a livable wage and health care, especially to developing artists.” About a month later, former New York Dolls front man David Johansen died at 75, just weeks after launching a GoFundMe to cover the bills from his cancer treatment. As gig workers in the truest sense, musicians and many others in the industry run into the same roadblocks to decent treatment and insurance as the average American, but their profession amplifies the problems to unbearable volumes.

“Around 50 to 55 percent of the general population has health insurance through their employer. In music, it’s about 19 to 20 percent,” says Theresa Wolters, vice-president of health and human services at MusiCares, the Recording Academy’s charitable arm. While acts on the three major labels are eligible to get SAG-AFTRA coverage, the only options for most artists are expensive plans from the Affordable Care Act marketplace, usually with high deductibles and little preventative coverage. “They have health insurance — they just can’t use it because they can’t afford the deductible or the out-of-pocket costs,” Wolters says.

Unlike the salary at a standard job, musicians’ income varies widely from month to month, making it a challenge to keep up with premiums or even make enough to stay insured. “Royalty compensation was an issue even before streaming, and most musicians aren’t getting paid out of an advance,” Kevin Erickson, director of the Future of Music Coalition, says. “Some lower-income musicians fall into that hole where they’re not making enough for a subsidized ACA plan but aren’t eligible for Medicaid in their state. There’s a lot of acute financial anxiety.”

The physical and mental tolls of increased touring often lead many musicians to ignore or delay treatments they need, which can then snowball into massive medical bills or worse. “If you get a serious injury or disease, even with the best insurance, a musician is in deep trouble,” says Aric Steinberg, executive director of Sweet Relief Musicians Fund. “The majority of them can blow through their savings in a month or two. If you get cancer, you might get chemo covered, but your recovery is not. And with all the gigs you miss, no one’s reimbursing you.”

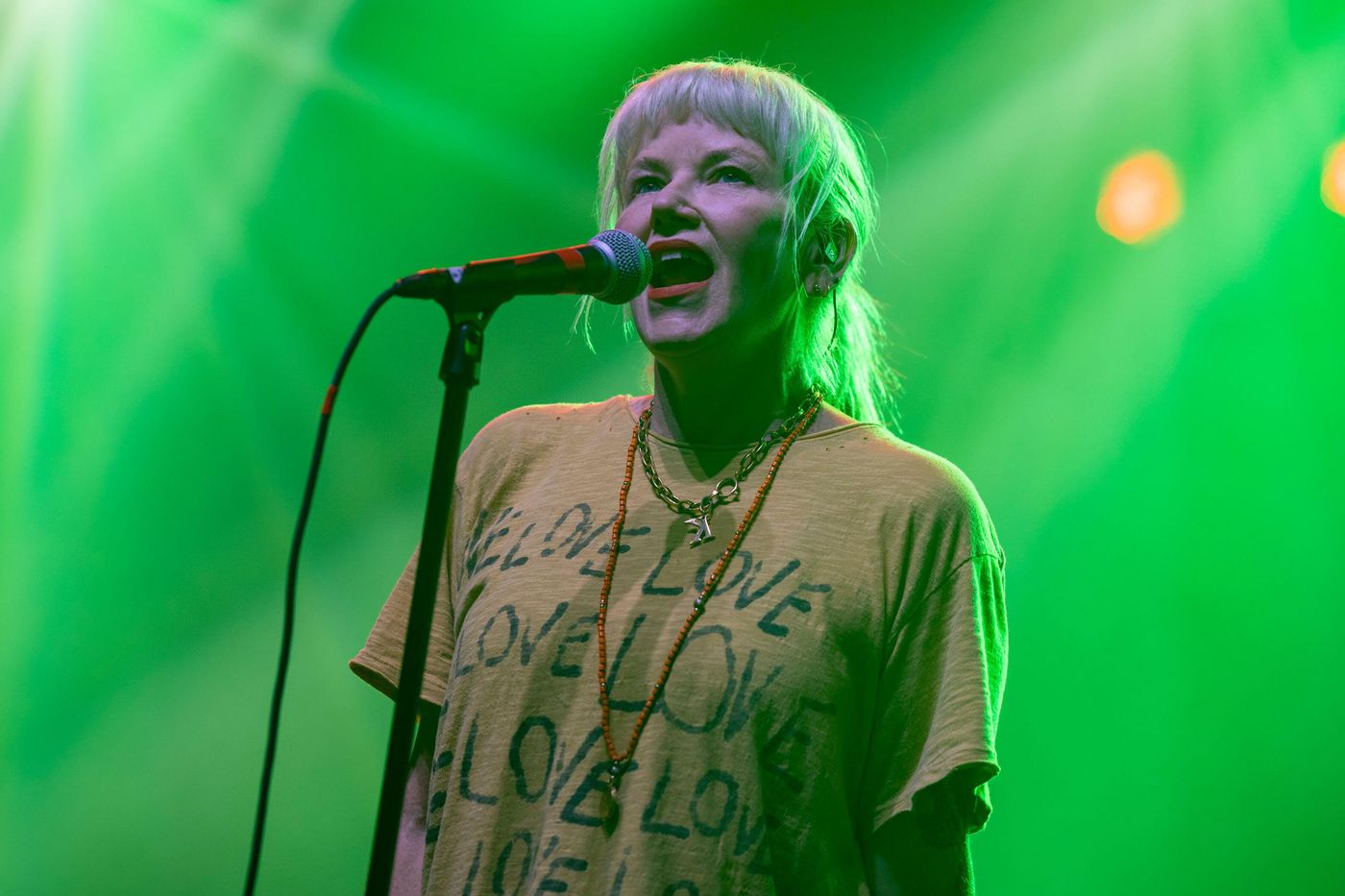

The past five years — with the pandemic, inflation, and now the Trump administration’s goal of kicking millions off Medicaid — have only made things worse, according to Michelle Lewis, who co-founded the advocacy nonprofit Songwriters of North America, or SONA, with Letters to Cleo’s Kay Hanley. “We used to hear every few months about a songwriter who couldn’t afford surgery or had to quit the business. Since COVID, it’s happened regularly,” she says. “Songwriters are still getting the smallest slice of the streaming pie, so many don’t have health care. Our foundation has grants for mental-health support and other medical costs — it’s not insurance, but it’s something.”

To truly understand how abysmal the American medical system is for musicians, we spoke to seven artists grappling with both managing and affording their health care. Here are their stories in their own words, from harrowing to hopeful.

“If I make a penny less than the threshold, I get kicked off insurance.”

From 1994 to 2004, I got a lot of radio play and my songs would get on a TV show or movie, so I was able to get SAG benefits. I had two kids, one of whom had a very terrifying health scare in infancy that required intubation and two weeks in the NICU. The bill was insane, but because I had health insurance, I didn’t have to pay out of pocket for it. But in 2005, I lost my health care because I didn’t make enough money to meet SAG’s earnings requirement. I’m constantly at the mercy of the union: If I’m able to get my voice on a show, I can rack up enough contracts to hit my earnings. But if someone else sings something I wrote, it doesn’t count toward my earnings, and if I make a penny less than the threshold, I get kicked off insurance. When that happened, every single person in our family had a preexisting condition. My daughter, who was in grade school then, has epilepsy, and my son had life-threatening RSV as an infant. I had to go on COBRA, which, for a family of four, is now a whopping $2,700 a month.

I’ve also struggled with alcoholism and addiction, and it was in 2010 when those chickens came home to roost. I found myself hospitalized and seeking treatment on a bunch of different occasions and had no way to pay. It was a scary time, having to be a cash patient and trying to battle a deadly problem with substance abuse. I needed inpatient treatment to not die of withdrawal, and insurance would only cover outpatient. Overall, I was in two rehabs, two detoxes, and three hospitalizations. My parents paid for my first rehab, which is crazy because I’m not from a wealthy family. MusiCares helped pay for a couple months of sober living after that, but it was a finite resource.

I think I had my SAG benefits for two of the bills, but the rest of them I ignored and hoped they would go away. I lost my benefits again because I wasn’t able to work for a year and a half — I tried, but I was just not in any shape to face the creativity, so I wasn’t really earning money. My marriage ended and Michelle Lewis, my writing partner for over two decades, said she wasn’t going to work with me again until I was sober for two years. It just so happened that the show we were working on, Doc McStuffins, went back into production when I’d been clean long enough, so that worked out beautifully. I’m used to stretching a dollar, and when I did make some pretty good money in the late ’90s, I squirreled it away. I’m not rich, but I was able to make sure the kids weren’t homeless and my daughter could get her epilepsy medication, which is very expensive. That’s why we’ve had to go back on COBRA three out of the last 12 years — you can’t ration epilepsy medication for a child or say, “We can’t afford it this month.”

“It taints your perception of humanity.”

My experience is that, whether you have insurance or not, the care is just shit. It’s overworked doctors who have no time for you, health-care workers who are beaten and broken, and an undertone of nastiness where you don’t even feel safe in the environment. I’ve had situations happen where I’m like, Was I just sexually assaulted? In like 2013, I fucked myself up on a video shoot and had abnormal bruising in my groin area. I thought it was a hernia, and I went to this doctor who was like, “That’s not a hernia. If it was a hernia, it would feel like this,” and they shoved two fingers into my groin as hard as they could. There’s nothing like realizing they’re just treating me like a fucking piece of meat. You have no recourse for it, you’re at their mercy, and you pay what they tell you to fucking pay.

Gender transition was the first time I had to consistently see health-care providers and get prescriptions filled. Even with health insurance, 90 percent of the time I feel like I’m just pissing money away each month. Recently, I got a plan that at least covers therapy for $40 a session, but as far as hormone replacement, I get fucking nothing; it’s all “elective.” In Chicago, there’s an awesome place called Howard Brown Health that provides excellent transgender care with discounted rates, but without that, it’s about $250 for an estrogen prescription alone and thousands a year for all the care.

In order to get on HRT in Florida, I was required to do six months of psychotherapy before I could go to an endocrinologist. They just want to hear you talk about wearing your mom’s dress or something sexual before they’ll say, “Approved.” Then the endocrinologist is still like, “Are you sure you really want to do this?” It wasn’t until I went to subsequent therapists that I was like, Wait a second, that was fucked.

In 2018 or ’19, I had facial-feminization surgery in Spain. It was cheaper, and they were the only doctors who insisted on an in-person consultation. Getting to experience the care over there was like night and day. But even though it was a positive experience, there were complications. I’m still not sure what caused it, but I couldn’t raise my right arm, my guitar-strumming arm, above my shoulder for a year. I didn’t have the option of taking time off to fully recover. I’m a working-class musician, so I had to get back out on the road a couple months later.

If our system weren’t so broken, I wouldn’t have as many apprehensions about undergoing sexual-reassignment surgery. I’ve had friends who’ve had these gender-affirming surgeries, and there’s always some side effect or result they weren’t anticipating. It’s such a major surgery that I just don’t feel safe for those reasons, and it doesn’t have to do with anything like, Do I want that? It’s a genuine fear.

When it comes to trans care, those communities are really at risk. My therapist recently said, “Stock up at least six months of hormones with the way things are right now.” Beyond knowing where drag performances are illegal and they might come for me as a transgender artist, it takes a lot of foreplanning to make sure you don’t run out of hormones on tour. There have been situations where I’ve been nervous; I had a layover once in Dubai, flying with syringes and estrogen, and it’s like, Am I going to get in trouble with this?

Dealing with it all burns you out, and it’s a completely different headspace from the creative side. It’s cumulative negative energy that ends up in your subconscious and comes out in your work. The silver lining is you get some good songs out of it. But it taints your perception of humanity, because you go to these people for care, and they’re just cruel. You realize the whole system is broken, religion is broken, government is fucking broken — you’re on your own.

“I finally had to give in and do a GoFundMe.”

My dad died from cancer, and all four of my grandparents and seven of my eight great-grandparents had cancer, so I knew I was going to get it at some point; I just didn’t think it’d be in my early 30s. I was on the road opening for the Killers doing a two-night stand in Reno. The first night went great, and then the second day, I couldn’t stop throwing up and had lots of abdominal pain. I went through with the show, got really dizzy and disoriented after, then went to the hospital, where I found out my appendix had perforated. They didn’t have an operating table large enough for me, so they weren’t able to take it out.

They did a CT scan and found something abnormal in my colon, but the image came out blurry because they didn’t have a machine big enough for me. They put me on fluids and antibiotics for five days and sent me home to Dallas. That was the first time I realized that the medical field isn’t accommodating to people my size. When I needed a PET scan, there were only three machines in the country that could fit me; I had to drive two hours each way to Shreveport for it.

Weeks later, as I was stepping out the door to fly to L.A. to do my Jimmy Kimmel taping, my doctor called: I had colon cancer. I told my fiancée and mom but pretty much kept it a secret from everyone else. I was locked in for the performance; I knew that a lot of things were about to change, so it felt like, I better do this right, because it might be the last thing that I do publicly for a while. Less than a month later, doctors removed a third of my colon, 52 lymph nodes, two sections of small intestine, and my appendix, because it all looked cancerous. Because of my family history, a doctor had told me to get a colonoscopy when I was 30, but insurance wouldn’t cover it and I didn’t have the money. I’d love to advocate for early colon-cancer screening here: I probably could have found that mass when it was just a polyp and never had to deal with all this at 33.

I had surgery in December 2023, then I had to heal up before starting chemo in February. I was on a cocktail of drugs that basically gave me heavy-metal poisoning. It sucked, but I put all my energy, when I felt good, into writing songs. After chemo, they did more tests that showed a ton of nodules in both my lungs. It had likely metastasized to stage IV cancer. To confirm it, they did lung surgery that took me out of commission for ten weeks. I sold my tour van and cut corners everywhere I could, but I finally had to give in and do a GoFundMe to keep the lights on. I hated asking for a handout, but it got to a point where there was really no other option. How much support I got was overwhelming, and it came with a good amount of guilt. But multiple people told me that it felt good for them to be able to help, and that helped me get over my pride.

A few weeks later, the doctor called and said, “It’s not cancer.” I was so high on pain pills that the news seemed too good to be true, so I called him back to get confirmation. It’s anxiety-inducing to know I could be told I need another biopsy or exploratory surgery, but I’m back on the road. Being on tour is an ass-whip when you don’t have any health issues, so it’s more difficult than before. But thanks to being on top of physical therapy, my breath work is better than it was before, so I’m happy with where I’m at as a performer. I’m just trying to roll with the punches, do what the doctors tell me to do, and be as healthy as I can be.

“I wasn’t creative and had no income for a long time.”

In June of last year, I decided to get one of those rental bikes we have in Philly. I was a few blocks from home when a car swerved into the bike lane, which is unprotected, and I fell at high speed over the handlebars. The woman drove off. I got up and was cut all over but thought I was fine. Then, when I tried to pick up the bike, my left arm couldn’t do anything. My bandmate Audrey took me to urgent care and they were like, “You need to see a surgeon immediately.” It was a shattered lateral condyle of the left humerus, as well as some muscle sprains around the elbow — one of the worst fractures they’d ever seen. But then they said it could be four months until I got the operation, so when I met with the orthopedic surgeons, I thought, Maybe my guitar credentials will help me get in faster. I’m not one to show off or brag about my perceived accomplishments, but it worked.

At the outset, they said it’d be three to four months after the surgery before I could pick up a guitar. When I had the accident, my band was less than two weeks from a festival, so that had to be canceled immediately. After the surgery, we were playing it by ear, because they told me I’d probably be in considerable pain for a long time. I wasn’t allowed to do any kind of strenuous activity for a couple months. Even if I wasn’t playing guitar, I might not be up for singing, because that expends energy.

Two months after the accident, we played a tour we had scheduled with Mary Timony, and my partner, Dylan Baldi of Cloud Nothings, filled in on guitar. I could do just enough on the guitar to teach him the songs, which got me back to playing earlier than they thought possible. I’m still in PT; I’m down to one appointment a week now, because otherwise I’ll run out of insurance-covered sessions. The co-pay is $95 per session, the highest the staff there has seen. I get acupuncture and massages, which have made a huge difference, but those aren’t covered. It’s still 20 hours a week of elbow drama.

My out-of-pocket max for surgery was supposed to be $700, but because of the way the bill was itemized — anesthesia, doctor’s fees, “hospital services,” etc. — I ended up paying $2,271.84 in installments after I negotiated discounts. I’d never done that before, but now I know that the second you call, they’ll offer to take a bill down 10 percent. But still, it was around $45,000 in medical expenses last year.

I wasn’t creative and had no income for a long time. I’m back to doing some writing and recording now, but it’s going way slower than it used to. The tendon pain is all gone, but the grip strength on my fretting hand is atrocious, and a lot of the nerve sensation hasn’t come back. But based on what the initial break looked like, they did not expect me to make any kind of recovery. I feel like that’s strictly because I’m able to take the time off to do what I need to do, which most people can’t. And that makes me furious.

“Does my country want me to die?”

I got invited for my first show in New York, and I remember walking down the street on the Lower East Side. My legs just stopped working. I fell down on the ground, and people were just walking by me. It was like pins and needles. Then, slowly, the feeling started to come back, and I just walked on. I thought that was really strange, but I didn’t think, I have diabetes and I’m about to die. I had two weeks of spells like that and lost about 20 pounds before I went back to Memphis and my job. I ended up in the emergency room, where they gave me insulin and said, “Your blood sugar is over 1,000 and a normal person’s is 80 to 110.” I was diagnosed with Type 1.5 diabetes, and that’s insulin-dependent, meaning you’ll die if you don’t take it.

I didn’t have any insurance when I was first diagnosed. I was working three to five jobs on top of playing music and saving up for my first record, then I got a $30,000 bill for the emergency room. I called the doctor’s office and said, “I’m so sick I can’t even get out of bed. Now you want me to pay you, and I don’t have it.” The lady I spoke to was very gracious. She asked what I could pay, I said $10 a month, and she let me do that. I gave them that $10 for five or six years.

Eventually, it wasn’t even a question that I could live without insurance, which cost $1,000 a month pre-ACA. After my body shut down, I slowly got to where I could sit up, and then I could hold my instrument in bed, then I started playing it, and I did some gigs, getting about $300 to $400 on a Saturday night between my fee and the tip jar. Then more gigs started to come, I raised $15,000 from Kickstarter, and luckily I got to meet Dan Auerbach, who produced my album Pushin’ Against a Stone. I signed with Concord, which helped pay off that emergency-room debt, and finally had a real plan for taking care of myself.

The hardest thing for me, as an artist on the road 150 days a year, is being able to get the medicine stock I need for the time I’m going to be gone. I cannot go anywhere in this world without several vials of insulin stored in my suitcases and my gear, because if I’m anywhere at any time and I don’t have it, then I’m gonna die. Every time I leave the house, I have to have backup pumps, sensors, needles, insulin, and candy or juice — like half a suitcase full of medical supplies. It’s about $1,200 out of pocket per month, plus the doctor co-pays, but I’m not crawling onstage weak and sick anymore. I feel grateful that people with pre-existing conditions can get insurance now. A person should never be in a nation as wealthy as ours and feel like, Does my country want me to die?

“I had a heart attack because I didn’t want to lose my job.”

In my 20s, I started getting pain in my heart, and I eventually found out I had lupus and other cascading autoimmune disease. At 31, after suffering from a different kind of pain that felt like acid being poured into my chest, I got the wonderful news that I have Prinzmetal angina, a very rare heart condition. Insurance companies basically say, “Don’t get it. We’re not covering it.”

My cardiologist really wants me to be able to follow my dreams, and he had a mastermind plan for how I could tour in a very particular way. I was able to pull it off for a few tours, but then I felt pressure not to be annoying around my former label. They’d marketed my disease really hard as part of the package — like, “Wow, a disabled pop star!” — but when it came to dealing with the actual disabled part, they were impatient. Once, I got super-dizzy when they wouldn’t let me wear an oxygen machine onstage in Denver because it wasn’t “a look.” Flights aren’t good for heart disease, but another time, we flew to Paris, and they made me carry a bunch of gear when I should’ve been resting in a wheelchair. They were footing the bill, so I did it. Two weeks later, I had a heart attack, all because I was ignoring my body because I didn’t want to lose my job.

Now, my medication costs are at least $1,500 a month, and my post-Paris ICU bill was $150,000. Most of my income now comes from OnlyFans; a lot of indie-music girls are on there under fake names. I hate it, but I don’t really know how else to make money when I’m in bed most of the time. There’s no shame in sex work, but for me, it’s a desperation thing. I might have fun doing it if it wasn’t paying for my $389 nitroglycerin bottle at CVS. I’d take anything else — working at a fast-food restaurant or grocery store — but I’d have to call out sick all the time.

I did GoFundMes, but I’m out of that game. Because I don’t look sick all the time, people thought it was all a scam. That’s when Sweet Relief came in, and they pay the doctors directly, but sometimes the fund won’t get any donations for a month. Now I have fantasies of moving to a farm and saying good-bye to the entertainment industry forever. There’s no place for people with chronic illnesses and disabilities there. It just gets worse and worse.

“The financial stuff weighs on me just as much as the physical.”

I’d just come home from touring in Europe to celebrate the 20th anniversary of my first album. I was feeling good in my mid-50s; I ran five miles a few times a week, ate well, didn’t smoke, no drugs. I had ten months of touring scheduled, then one night, while out with some friends, I felt extreme burning pain in my hips, legs, and lower back. I tried to fake it through our dinner but ended up on the restaurant floor, couldn’t get up, and needed an ambulance. After two different hospitals, several MRIs, and a lot of late nights, they found I’d had a very rare spinal stroke.

I was in the hospital for three months, not able to pick up a guitar for weeks. Insurance covered some things, but once you’re discharged, you’re on your own. They stopped paying for PT and didn’t cover the wheelchair that NYU Langone said I needed and had fitted me for. I was instead sent home with a $200 wheelchair, which I still use. I had nowhere to live — my apartment was a walk-up, so I had to stay in hotels with handicap bathrooms that were expensive. I needed help getting around and into the bathroom, but they don’t cover home care or my medical supplies.

When the doctors said there was no hope for recovery, we looked into alternative treatments. I ended up going to Buenos Aires for six months of stem-cell therapy, plus five days of PT a week. It cost $10,000 plus expenses, but I came home able to use my legs, straighten my body, and move with a walker. It’s been tough, but the good side is that the music community — the artists, the fans, the organizations like Sweet Relief — has been so generous. I didn’t want to hold out the cup, but when someone’s in need, they rally.

I try to be grateful for the things that I have. I don’t like being Mr. Sad and Depressed, but it’s hard. I did two dates overseas to see what it would be like — handicap rooms were twice the price, plus paying for the nurse, so it ate up so much of what would have been my income. We’re still fighting with the insurance company over the wheelchair and hired a medical advocate to contest it. The financial stuff weighs on me just as much as the physical — the anxiety you’re constantly fighting off to stay positive and healthy and healing. It’s a battle.

It’s been two years now — I’m able to get up with braces and a walker, but I have no feeling in my legs from my upper thighs down. I believe in fighting through this and finding ways to keep working on my music. I’m currently creating a one-man show about my life, something where I can perform and not have to travel. I’m doing everything I can to defy the odds to get up there with my band and sing and dance again. It’s the unknown, but I still believe I’m going to get better.

“You realize the whole system is broken.”