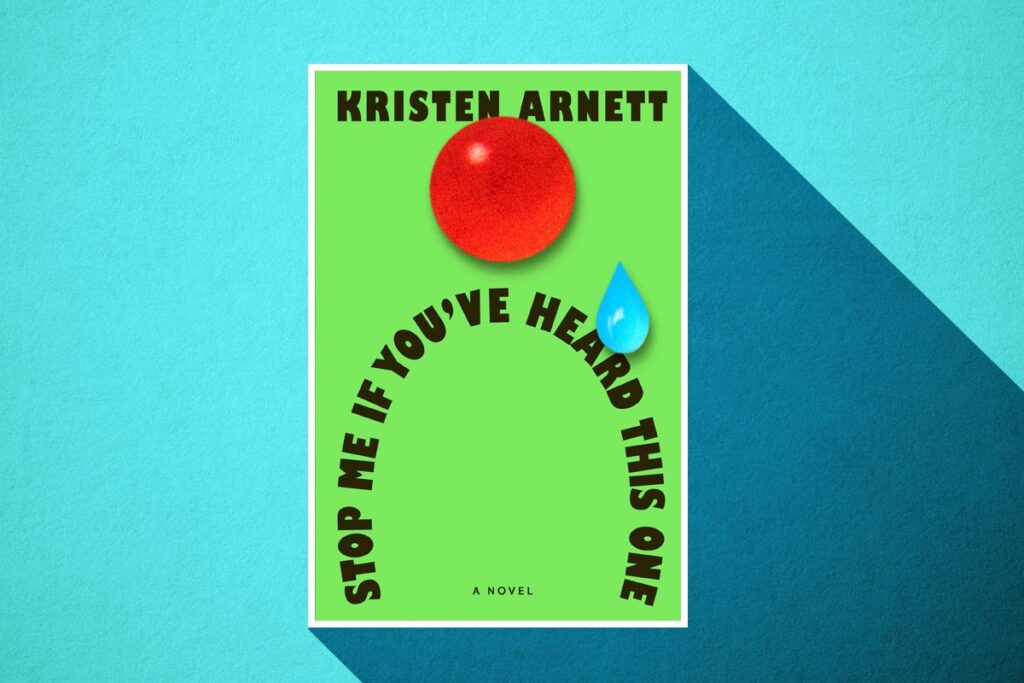

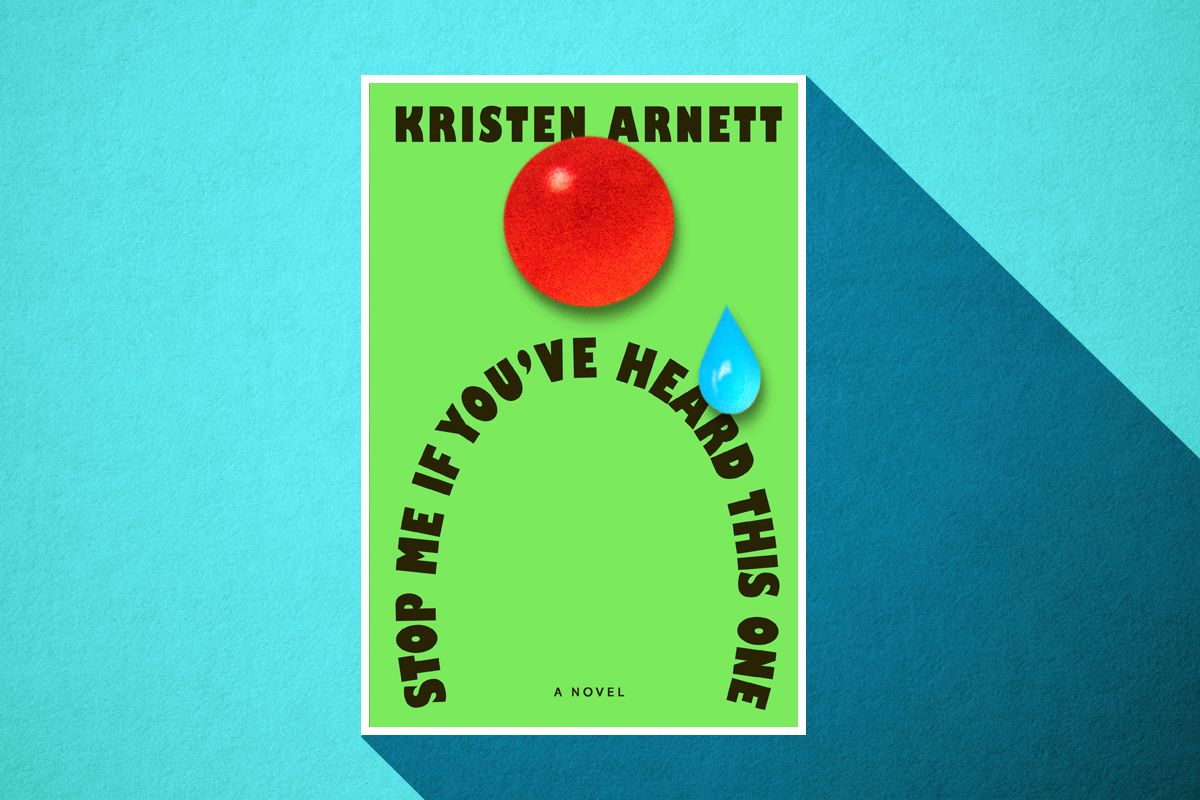

Kristen Arnett writes a hell of an opening scene. Her debut novel, 2019’s Mostly Dead Things, began with a studious description of a taxidermist skinning a white-tailed deer; in her newest, Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One, the curtain rises on a lesbian clown, hired to entertain a children’s party in suburban Orlando, slipping off into the bathroom for a sweaty assignation with the mother of the birthday boy. The scene is unaccountably hot — not because one of its participants resembles “a deranged Shirley Temple who just got back from Burning Man,” necessarily, but somehow not despite that fact either. It’s a heady rush of vivid detail (“a swath of black hairs lining the top of her right ankle, a sprawl of red dots climbing the inside of her bare thigh from a shaving rash”) and nervy humor. “Could you use the clown voice?” the mother asks. “I mean, I’m paying for the experience, you know?”

“I bet Bunko’s got something just for you,” her paramour replies.

A cowboy with a deathly fear of horses, Bunko is the creation of a professional clown named Cherry Hendricks. Notwithstanding these moments of suavity, Cherry is an enormous mess — which makes her a classic Arnett character. This author’s specialty is queer women in Florida who are Going Through Some Stuff: They drink too much, speak injudiciously, and have weird relationships with their families. Within this broad rubric — and against a familiar backdrop of Publix supermarkets, suburban sprawl, and 7-Eleven parking lots — Arnett finds the ingredients for a fascinating range of stories, in which scenes of gonzo humor bring levity to portraits of prickly, frequently self-sabotaging characters. “Normalized” is an overcooked word, but Arnett’s is a blossoming oeuvre that normalizes a rich vision of a specific — and, for some of us, quite relatable — lifestyle: that of the gay dirtbag. Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One is about a frustrated clown trying to get happy; it’s also a timely, tender exploration of the subterranean joys and growing challenges of queer life in the South today.

Arnett’s most recent novel, 2021’s With Teeth, revolved around a work-from-home mom who — grappling with a difficult child and a failing marriage — becomes more and more emotionally unregulated as the book goes on, undone by the widening gap between her life and what she thought it would become. In tone and structure, Stop Me is closer to Mostly Dead Things, whose protagonist, Jessa, deals with the fallout of a series of traumas: Her taxidermist father died by suicide, and the love of her life (who happened to be married to her brother) ran away. Written in a wry, lively first person, each book involves characters pursuing passions that are decidedly not for everyone. One great pleasure of both is Arnett’s respect for craft, meticulously described: the price Cherry pays for quality greasepaint; the taxidermist’s delicate maneuvers to “debone small game without ruining the pelts.” Both Jessa and Cherry may be cauldrons of insecurity, but in their work they feel in control. As Cherry reminds us, clowning is her art, not just a hobby or a way to pay the bills.

Not that it pays the bills anyways. Stop Me’s plot, such as it is, has Cherry attempting in fits and starts to get her life together. On the home front, she’s grieving a brother who died in a drowning accident, and trying to maintain a relationship with a mother who doesn’t approve of her lifestyle (the clowning lifestyle, that is — Mom’s also gay). Her job at an aquarium-supply store has her living paycheck to paycheck. She’s pursuing an older woman who works as a professional magician, though Cherry’s not sure if what she wants out of the relationship is a mentor or a sexual partner. She ultimately splits the difference: “Mentoring with benefits,” she calls it.

Cherry is an old-fashioned smart aleck, something of an overexplainer, and a deeply earnest narrator who peppers the story with corny paeans to the creative life, saying things like “In order to perfect my art, I must let it swallow me whole.” Her constant invocations of the “dreams” she’s chasing can lapse into wearying self-help pablum. But she uses that pablum to nourish herself, amid rising feelings of directionlessness. And, anyway, silver linings in Arnett’s fiction inevitably come trailing clouds. In the opening scene, Cherry is chased out of the bathroom window by the husband of the woman she’s been fucking: “It’s always the jokes that go off the rails that work best, I think, as my own shoe flies from the window and whacks me hard in the neck. The beauty of it stuns me for a moment.”

An undertow of sadness churns beneath the slapstick, a combination that inescapably brings to mind Karen Russell, whose 2011 Swamplandia! is a modern Florida classic. That novel also centered on the daughter of a family at loose ends following the loss of one of its members; it, too, featured a scrappy entertainment enterprise (in this case, an alligator-wrestling attraction) struggling to survive against gazillion-dollar corporate competitors. In Arnett’s prose and in Russell’s, whimsical surfaces and playful language conceal a darker heart — perhaps an inevitable narrative approach in a state whose plasticky theme parks project only the illusion of control over the natural world, a state where no gated community will ever be secure enough to prevent the occasional Pomeranian from becoming alligator food.

Loss is all around in Stop Me, and not just in Cherry’s family. Central Florida — a place where Arnett’s writerly claim is now as firm as Flannery O’Connor’s was to rural Georgia — is increasingly unlivable: expensive housing, low-paying jobs, unchecked gentrification. Even as she moves through it in the present, Cherry’s world takes on an almost nostalgic cast. There’s a texture to the places Arnett describes, a grain, like seeing photographs shot on real film. This Florida is a place so ramshackle, so contingent, that — no matter how well loved — it can never survive. Cherry and her friends hang out at a mid-century home turned makeshift punk space they call the Pussy Palace, for its pink coloring and many queer patrons. “It’s just ours,” Cherry explains. “We DIY our own places here because if we don’t, we wouldn’t have any.” One day she comes by and finds it boarded up.

Punk spaces aren’t the only things on uneasy ground. Arnett does as fine a job as I’ve encountered capturing the tidal nature of the emotions one experiences as a queer person these days, how the anxieties surge and recede, floating always beneath the surface but rarely at the dead center of our lives. A bravura scene at a children’s fair, for example, devolves into brief, bloody chaos following the arrival of “men in black tactical gear” protesting a drag story hour. Cherry rues the random nature of these instances of trauma, which explode only to be forgotten five minutes later, subsumed beneath the next crisis. “It’s like whiplash. That’s the only way I can describe it,” she muses. “Over and over again, violence, and then we’re expected to immediately return to normalcy.”

But then, of course, life goes on. Cherry doesn’t have a choice — the rent is due. Arnett threads the uneasiness of queer life today into a broader tapestry of social precarity; this is a book about being queer, and pursuing creative practice, in a society increasingly organized around the suppression of both. She even revives the old debate over “selling out,” a notion historicized nowadays as a boutique Gen-X concern, when Cherry has to decide whether to accept an offer for a cushy theme-park gig. If this all makes Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One sound like a downer, it’s not really. Recall that our protagonist is a gay clown with a thing for MILFs.

The clown herself represents a refreshing counterpoint to the archetypal comic figure of the age: the right-wing stand-up; the self-styled subversive whose most passionate commitments are to social hierarchy (provided he’s somewhere near the top). Stand-up is “all focused on the self,” Cherry notes. “It’s the I, not the you.” Her clowning is a communal act, relying on interplay between performer and audience and oriented toward mutual pleasure. Cherry makes a connection between clowning and queerness at the beginning of this book that’s a little overstated, and that, characteristically, she probably didn’t need to spell out quite so explicitly. (Both inspire irrational hatred in others, etc.) But the general point stands as a principle governing this novel: Both queerness and art require a kind of boldness, a willingness to disrupt the mechanical operation of the world to make a space for yourself in it. With wonder otherwise in short supply, Cherry knows, you’ve got to manufacture your own — and this itself is a matter of craft, requiring care and devotion. You won’t find it at Disney World.

Kristen Arnett’s specialty is queer women in Florida who are Going Through Some Stuff.