Not all years have an obvious emerging theme in comedy specials, but many greats of 2025 happen to come from established comedians in middle age. Perhaps not coincidentally, several of the best specials are also about people realizing they’re going to die. Mike Birbiglia’s The Good Life, Marc Maron’s Panicked, Cameron Esposito’s Four Pills, and Bill Burr’s Drop Dead Years are all hours of comedy about reckoning with mortality, and each in their own way is a lovely, absurd, painful depiction of someone staring into an abyss and choosing to laugh.

That’s not the case for all the year’s specials — Steph Tolev’s Filth Queen is a rapturous ode to other elements of human debasement, namely sex and poop — yet it does give the year a somewhat unusual feeling of gravity. But don’t worry! Amid all the looming consciousness that our time on earth is precious, there are also specials unerringly devoted to utter stupidity, and even the comedians fixated on mortality are delivering life-affirming material, too. Here are the best specials of 2025 so far.

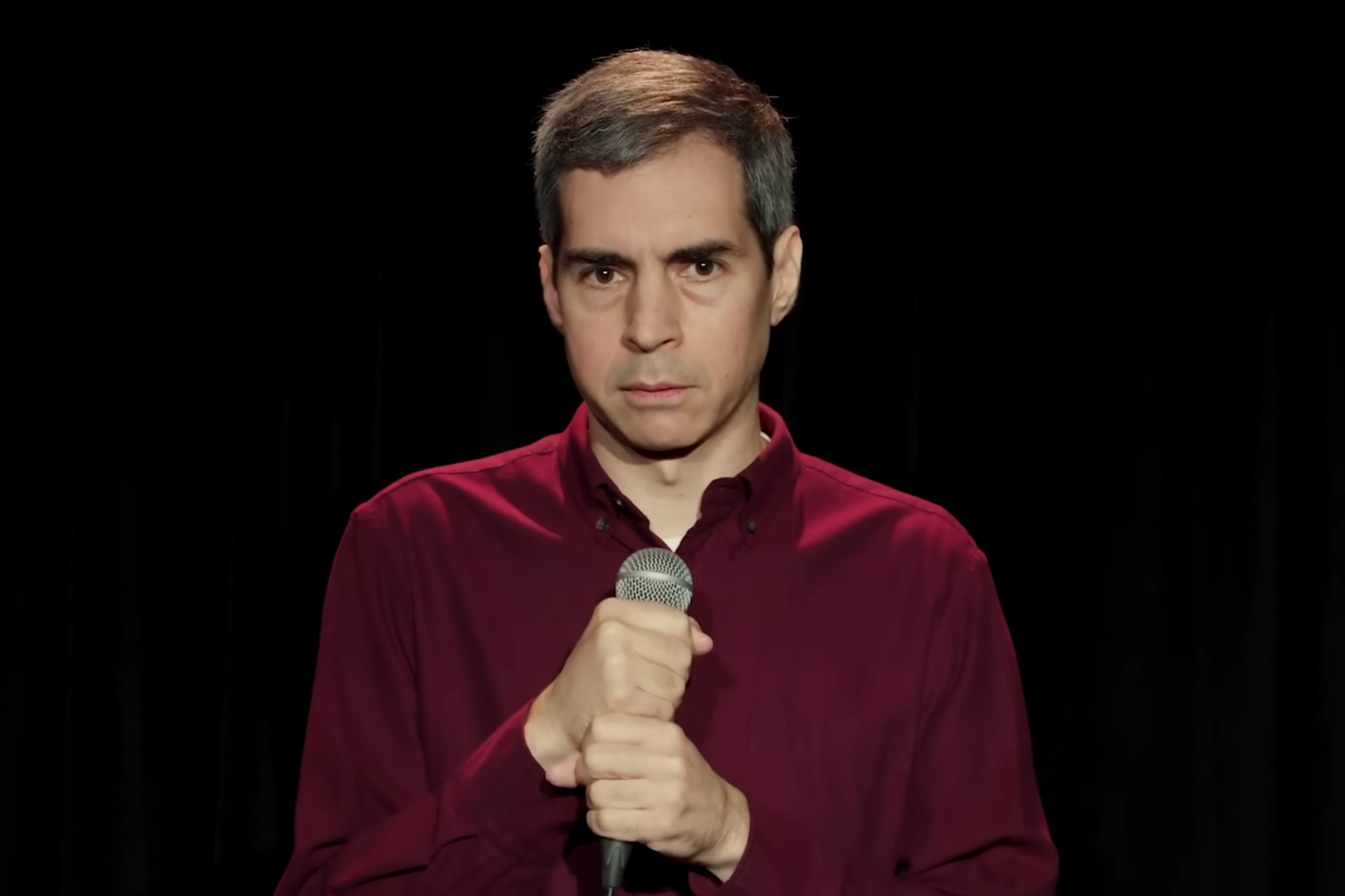

Marc Maron, Panicked (HBO, HBO Max)

It’s not exactly Maron’s fault that he has become such a great comedian for this moment in history. At another time, a perpetually anxious comedian who can’t keep from ranting about his paranoid worries about the end of the world probably would not feel like such a helpful guide to life. Without being too focused on anti-Trump material or easy political frustrations, though, Maron’s new special speaks to a national mood better than anyone else so far this year. His closing joke, which includes a Taylor Swift song that feels pleasantly incongruous with the rest of Maron’s persona, builds to a surprisingly hopeful ending while being a joke about Maron’s acceptance of death. Even in a special with an actual Taylor Swift song, however, the obvious best cameos in Maron’s comedy are his cats. Nothing adds depth to an irascible curmudgeon quite like an irrational love of pets that do not love you back.

➼ Read Kathryn VanArendonk’s full review of Panicked and watch Jesse David Fox’s Good One interview with Maron.

Steph Tolev, Filth Queen (Netflix)

Filth Queen does exactly what it says on the tin: It is proudly and thoroughly gross. Tolev catalogues the many horrible qualities of the human body with the care and consideration of an obsessive collector. Each fart is treasured for its own unique qualities, each shit placed on a comedic pedestal to admire and enjoy. Tolev is messing around with a particularly subversive form of gender play, of course — she loves to toggle in and out of a cutesy-girl “oop!” before diving back down deep into her voice’s lower registers, becoming a squelchy muck monster that lurks in men’s nightmares, clogging their toilets before immediately stripping naked and straddling them. The entire hour is a fascinating, glorious middle finger to various forms of bodily shame, and with Tolev stomping around the stage in huge black combat boots and a pleather jumpsuit, female too-muchness gets a new standard-bearer.

Atsuko Okatsuka, Father (Hulu)

The simple, remarkably capacious premise of Okatsuka’s new special is that, actually, she’s the father. It takes some introductory unpacking to get that idea, which gives Okatsuka room to pull in anecdotes from her marriage, her childhood, and how she thinks about her own job as a comedian, but once she lands on that one big idea, it’s quickly obvious how powerful it is as a framing device. It allows her to talk about all the topics comedians love to rely on as relatable material for audiences, things like parenthood and gender roles in a marriage and the relationship you have with your parents. But Okatsuka’s conceit immediately offers a way to access all those things without feeling trite or obvious because they’re all instantly presented with enough self-reflection and distance that the anecdotes can be funny while connecting to the deeper laugh of realizing this is who she is, this is how she thinks. “I’m baby” is not enough of a thesis to feel satisfying. “I’m baby, which makes me father, which makes us all think about the expectations of fathers and mothers, and also isn’t it beautiful to be baby, and that’s why I’m never having a baby” — that’s a special worth watching.

➼ Watch Jesse David Fox’s Good One interview with Okatsuka.

Mike Birbiglia, The Good Life (Netflix)

Given Birbiglia’s track record, it’s not exactly a surprise to turn on a new hour and discover a painstakingly crafted meditation on the meaning of life. That is his bag, after all. But it’s still a magic trick every time it happens, and by embracing a more casual mundanity in a lot of its storytelling, The Good Life sneaks its way into the top tier of Birbiglia’s work. It is not pegged to any one enormous event or life-changing discovery — it’s dad comedy with comfortable strolls through trampoline-warehouse birthday parties and puberty and how to have fights with your wife. But after a few specials that explicitly reached for transcendence, The Good Life succeeds precisely because it’s happy to bury its intensity a little, to forgo some of the big formal playfulness and relax into being a guy on a stage talking about his life. It’s still Birbiglia; this thing’s got plenty of structure. It has been deliberately made a little softer around the edges, though. His stories have more sway and squish to them. It’s a good fit for where he is now. Comfortable. Happy. Trying very hard to be good with being comfortable and happy.

Brent Weinbach, Popular Culture (YouTube)

For every new cohort of clubby punch-line comedians and truth-telling trauma explorers, somewhere a weirdo rises. In this case, it’s Weinbach doing a bizarre smattering of impressions with no coherent design except that they’re all odd mash-ups and off-center angles, regularly designed as setups with little payoff, strung together by Weinbach’s near-affectless deadpan delivery. Experiencing Popular Culture is like sitting down with an anachronistic piece of comedic technology — Weinbach is basically a broken radio perpetually dialing in and out of random transmissions from the recent cultural past. Sometimes, the radio gets stuck on one channel too long, as in a section when Weinbach cannot stop singing Michael Jackson songs with lyrics adjusted to reflect Jackson’s alleged crimes. Even then, though, the total experience is so disorienting that its mere existence is half the pleasure. Sure, why not an impression of a guy who responds to requests from a waiter with only weird facial expressions? Or an extended performance of someone seriously pitching new, clear nonbinary pronouns, and the suggested word is heirm? Weinbach’s not going for breadth; this is an exercise in getting away with as much as possible while explaining absolutely nothing.

Cameron Esposito, Four Pills (Dropout)

Calling Four Pills a pandemic special is unfair — Esposito’s new hour is about marriage, divorce, despair, egg retrievals, mental health, and what it’s like to discover things about yourself after the age of 40. It’s especially an hour about Esposito’s bipolar diagnosis, and she performs that discovery by playing with how the audience encounters what will later become clear are manic episodes. At first, it’s a fantastic opening joke about the time Esposito had surgery on her butthole and then she resets into what feels like it’ll be a straightforward “what I’ve been up to” kind of hour. Gradually, though, as she builds her way toward a dangerously manic period, the special swerves into brief blips from another version of Esposito’s set, one in which there’s no audience present to make clear that this is all meant to be a joke. Or is it? And when isn’t it, and why? The comparison to pandemic specials is useful, though. In the best cases, post COVID-specials have often been spiraling acts of existential reassessment, daring and intense and probing. Like that genre, Four Pills is an exploration of what happens when you cannot do stand-up, which makes its existence feel all the more precious.

Bill Burr, Drop Dead Years (Hulu)

Is there anything better — sharper, more ticklish, more thrilling — than Burr doing comedy about how he’s slowly realizing that he and everyone else will eventually die? This sounds facetious but is not at all. After Burr’s years of perfecting a comedic persona that buries an almost tender love of humanity under a miles-thick crust of outrage, he has spent the past decade on a slow arc toward baffled enlightenment, and it has been one of the most fascinating journeys to follow in comedy. Burr is still Burr. He cannot help but start Drop Dead Years with a volley of third-rail vocab (trans people! Feminists! Ugh!) just so everyone knows he’s Still Got It. After that throat clearing, though, Drop Dead Years is so poignant and considered on topics like parenthood, mortality, and meaning that it would take surprisingly little work to repackage the whole thing as a one man show at a black-box theater. Ahem, not that Burr ever would. He’s a hard-joke comic, and don’t put him into that artsy nonsense.

➼ Read Jesse David Fox’s interview with Burr.

Rosebud Baker, The Mother Lode (Netflix)

There’s a version of Rosebud Baker’s special The Mother Lode that leans much further into its premise and takes more victory laps about the cuteness of its central idea. That version would’ve been a worse special! Baker’s approach to the slowly developing genre of a maternity and early-motherhood comedy special is that some of it was filmed during her pregnancy and some was filmed several months after she gave birth; the special freely cuts back and forth between the two performances. A soppier edit could’ve made the whole thing more obvious and more pleased with itself by pausing between the cuts, emphasizing the pregnancy more, using music or camera-angle cues to really make hay out of the idea. Instead, The Mother Lode offers the relatively radical argument that it’s just Baker, the same person, before and after. Sometimes, she talks about her hopes that her daughter is “a huge cunt,” and sometimes, it’s about the obnoxious pressure to breastfeed, but her perspective has not done a 180-degree turn. Of course, there has been some transformation, but it’s subtler and harder to characterize than you may assume. Baker remains the anchor, and amid the examples of maternity specials about physical devastation and total personality shifts, it’s an astonishing relief.

Roy Wood Jr., Lonely Flowers (Hulu)

Although Roy Wood Jr. builds and shapes his main idea throughout this hour, the standout is the closer, a truly fantastic story about taking a girlfriend and her son to see a children’s-theater bubble show. That joke is the culmination of everything Wood wants the special to say — it is an experience of awe and astonishment, but all that is prelude to Wood’s epiphany about emotional intimacy in a romantic relationship, his desire for an intensely meaningful connection with someone, a relationship that goes beyond convenience, pleasure, and comfort. The entire hour plays with variations on interpersonal connection, sometimes in brief interactions between strangers, sometimes about parenting and childhood, and sometimes seen through Wood’s experience of fame, but the bubble-man story is Wood at his most personal and captivating.

Established comics contemplating their own mortality and a rapturous ode to other elements of human debasement.