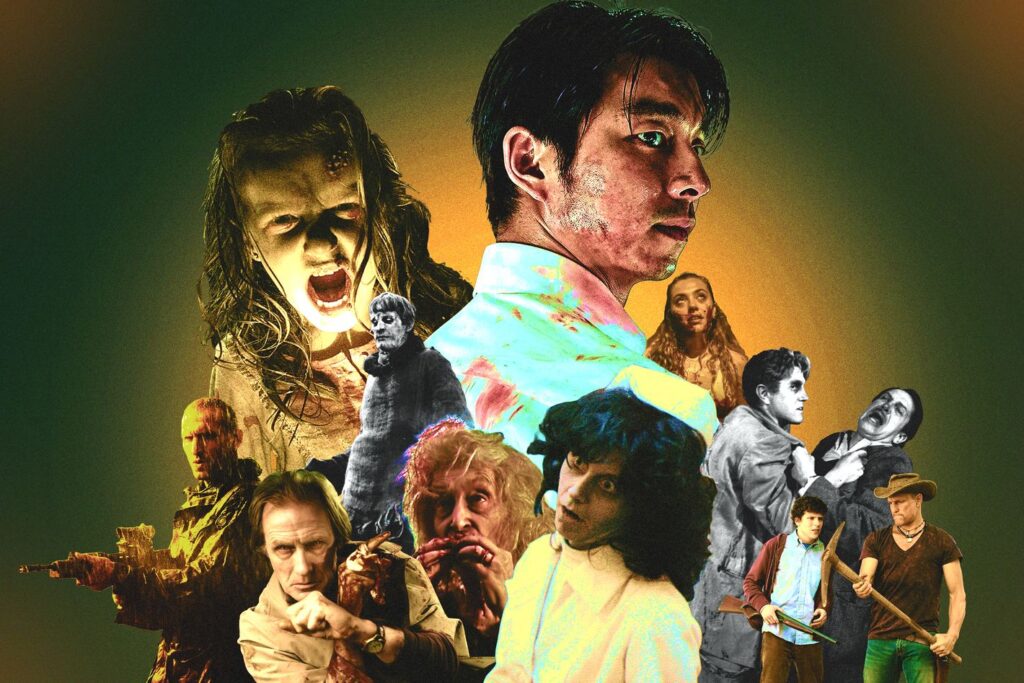

This summer, director Danny Boyle returns to the zombie series that helped reinvigorate the genre. But unlike 2002’s 28 Days Later, the appropriately named 28 Years Later isn’t emerging in a barren field. The last few decades have seen a mass proliferation of the undead on film, from blockbuster adventures and comedies, to award-winning TV series, to thoughtful independent ventures, to international sensations that lit up the film-festival circuit. The zombie is one of the most oversaturated horror symbols of our time, but our appetite for it is seemingly endless. We heartily consume zombie media like the flesh-eating ghouls onscreen.

But zombies aren’t exactly a new product, either. They emerged onscreen during horror’s first cinematic boom period in the early 1930s and have stuck around in some form ever since. There may have been dry periods and eras when it seemed like a cure had been found and the undead had been put to rest. But as these 28 standout examples of the genre show us, the art of the zombie is borderline unkillable. We can bury it as deeply as we want to, but the genre always manages to rise from the grave.

White Zombie (1932)

Often considered to be the first feature-length zombie film, White Zombie hails from a different era — one when Bela Lugosi, then the most famous horror star on the planet after his role as Dracula the year prior, appeared in at least a handful of fright flicks each year. In White Zombie, he plays “Murder” Legendre, a voodoo master who can turn people into zombies and force them to work in his Haitian sugar mill. If there’s one thing that separates early zombie films from more modern tropes, it’s that the early ones typically relied on voodoo or mind control to explain their walking undead. White Zombie isn’t the best of the early genre (and it’s only the third-best Lugosi film of that year), but the themes it established carried it through the next three decades.

I Walked With a Zombie (1943)

The Russian American film producer Val Lewton came to RKO Pictures with the mission of pumping out as many horror films as possible, as cheaply as possible. By the time he left the company only a few years later, he’d amassed one of the finest horror lineups of any studio in history. Among them was I Walked With a Zombie, an atmospheric film that once again takes us to a sugar plantation and the whispers of the undead that surround it. Director Jacques Tourneur brings his trademark mood to the proceedings, but what stands out most are the themes of racism and colonialism and how they tie into our vision of folklore and traditions that we don’t necessarily understand. When George Romero got his hands on the genre years later, zombies would function as clear metaphorical subjects for society’s ills. But I Walked With a Zombie proves that they made for apt symbols from the beginning.

Creature With the Atom Brain (1955)

In the 1950s, the effects of nuclear radiation made for prime science-fiction — and you didn’t have to be a 15-story dinosaur in Tokyo to take part in them. Creature With the Atom Brain sees a gangster force a German scientist to reanimate the dead with atomic radiation in order to pull off crimes (recalling both Frankenstein and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, films that fit neatly alongside the zombie genre). Creature is a pretty no-frills-attached look at zombies, and much of it is a hoot as we watch these corpses rampage around.

The Last Man on Earth (1964)

Based on the novel I Am Legend by Richard Matheson, The Last Man on Earth is among the first “zombie” films (though they’re given many of the classic traits of vampires here) to harness the postapocalyptic setting that would eventually become the genre standard. The film eventually pulls off a twist that scientist/zombie hunter Morgan (played by Vincent Price with gusto) might actually be hunting people who are still technically “living,” but its most effective bits center on Price’s desperate search for humanity in a seemingly dead world. The eerily empty locations, the degradation of a mind left to wander, the longing and loneliness — The Last Man on Earth is a test run for countless stories to come.

The Plague of the Zombies (1966)

The Plague of the Zombies isn’t the first zombie film in color, but it’s among the first to really tap into the cinematic potential of a decaying corpse, especially when you can lavish so many beautiful grays and greens on it. The cause of the zombies is once again voodoo rituals and, though it’s a Hammer Film production (the British studio had become famous for doing a little more bloodletting than its American rivals), flesh-eating isn’t in the zombie repertoire. However, director John Gilling does the finest job yet in portraying zombies as a horde that can surround you no matter how slow they’re shuffling. Combine that with a dreamlike atmosphere and you have a film that’s both of its time and a little ahead of it.

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

The father of the modern zombie film, Night of the Living Dead feels like the genre’s eureka moment, when the pieces that will cause its 20th-century golden age to finally come together. Director George Romero has a relentlessness that previous filmmakers lacked, not only giving us sights of the menacing zombies, but what happens when they finally start to munch on you (the meat was donated by a local butcher). It’s got one of the most memorable endings in all of horror: Ben, the sole survivor of the zombie attack on a farmhouse, is absentmindedly shot by a member of the ragtag militia that has formed to deal with the undead. The fact that Ben was a Black man and the surviving protagonist in a genre that leaned remarkably white in a decade defined by racial tension, is also very much of note. Though it would kick off cinema’s most unkillable zombie film series, Night’s effect remains singular. They’re coming to get you, indeed.

Tombs of the Blind Dead (1972)

Night of the Living Dead was part of a worldwide horror renaissance of sorts. A Spanish-Portuguese effort in that cohort, Tombs of the Blind Dead, has the soul of a dark fantasy and the heart of an exploitation film. Parts of it are downright beautiful (its director, Amando de Ossorio, is one of the best horror filmmakers to ever come out of Spain) as an army of resurrected Knights Templar travels around on horseback like blood-drinking Ring Wraiths. Like Night of the Living Dead, its gory finale is an unforgiving one, and it would spawn three very loose sequels. Akin to the wider horror movement at the time, Tombs wasn’t interested in happy endings.

Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things (1972)

Bob Clark would eventually be known for the hypersuccessful sex comedy Porky’s, the holiday staple A Christmas Story, and the influential slasher Black Christmas. But before that run of hits, he was just a director trying to make a name for himself and, as was the common method, he used a low-budget horror film to do it. Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things wears every bit of its minuscule budget on its sleeves, and though it isn’t the first zombie comedy, it’s the first one that managed to retain its charm. Despite its slow beginning, the dedication of the young cast (playing a theater troupe, which no doubt allowed them to poke fun at all of the things that they were going through in real life), and Clark’s eccentric style carried Dead Things into the realm of the cult classic.

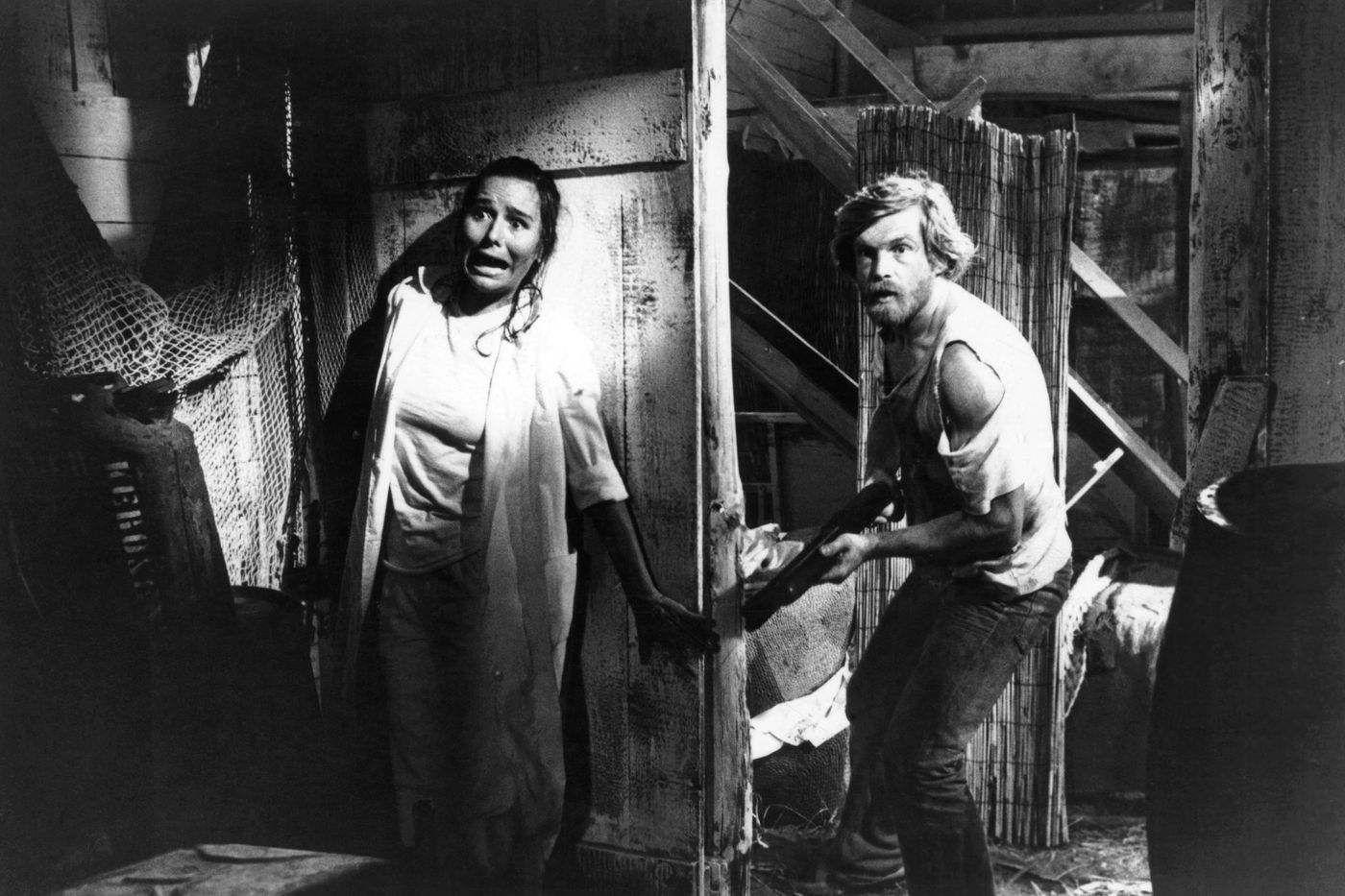

Let Sleeping Corpses Lie (1974)

By the mid-’70s, Night of the Living Dead had become not just a hit but a blueprint, and the zombie films to come had to adjust to its now-trendy brutality. Let Sleeping Corpses Lie, a.k.a. The Living Dead of Manchester Morgue, is among the best of the era, combining bloody kills with a fog-thick atmosphere. Its director, Jorge Grau, was underappreciated in his time, but he makes the most of his shocker about zombies stalking a farming community after they’ve been resurrected by ultrasonic radiation. Though films like Night of the Living Dead (and Romero’s The Crazies, released a year before Sleeping Corpses) had begun to tie zombies to the downfall of mankind, Corpses feels like a fully realized version of the theme. The terror comes to quite literally infect every scene, and the credits don’t provide an ending, but a relief.

Rabid (1977)

Released almost a decade into his feature-film career, Rabid feels like David Cronenberg finally cornering some of the genres that he’d been experimenting with for a while. Most notably, his penchant for body horror, which takes the form of a stinger/sex organ that appears in the armpit of the lead character Rose, turning everyone it touches into a murderous maniac. Like many young horror directors, Cronenberg works with a low budget here, but he has enough brazenness and big ideas that this wonderfully nasty film manages to crawl under your skin and stay there. He’d play around with a lot of the same themes in later years, tinkering with the stories like a chef with a beloved recipe, but Rabid ensured that, even amid a wave of new blood, Cronenberg was special.

Dawn of the Dead (1978)

Both a zombie epic and a treatise on how American consumerism dooms us into a dead-eyed existence, Dawn of the Dead is often considered to be George Romero’s finest hour. Though it’s huge in scale — it’s a film about the end of the world, and even a climactic escape by helicopter feels bittersweet — the malaise and claustrophobia of the shopping mall that the four leading characters are trapped in create something surprisingly personal. When Peter has to shoot his zombified friend Roger in the head after an agonizingly tense sequence, you understand that the zombie film, despite its hordes of groaning extras, can be a nice character piece, too. The script is very important, even if most of the dialogue is someone grumbling for human skin to tear into.

Zombi 2 (1979)

George Romero might be the most famous name linked to the zombie genre, but not too far behind is Italy’s “Godfather of Gore,” Lucio Fulci. Where Romero’s tastes leaned literary, with a big emphasis on prescient themes, Fulci’s was hallucinatory, as if you were watching his films through a high fever with a cold cloth on your forehead. Zombi 2 (Named that because a reedited version of Dawn of the Dead had been released in Italy as “Zombi” and the producer wanted to cash in), might be the apex of the genre as a vehicle for gory set pieces, from the woman who gets a big shard of wood impaled in her eye to the many, many satisfied zombies chewing on a shocked victim’s flesh. Combine that with a scene where a zombie tries to bite a shark and you realize why this film has spent most of its existence banned in the U.K.

Re-Animator (1985)

Based on the H.P. Lovecraft story “Herbert West — Reanimator” and directed by low-budget king Stuart Gordon, Re-Animator is filled to the brim with blood and copious, well-timed bits of dark humor. Much of it comes from the character of West himself, played by Jeffrey Combs in a role that would turn him into a horror fan favorite, but the whole film relishes just how macabre it can get. (Before the zombie-thwacking climax, a disembodied head being held by its decapitated body attempts to perform oral sex on a woman, so that’s what you’re getting into with Re-Animator.) Gordon never quite got the acclaim of men like Romero or Cronenberg, but he had a sense of daring that was bigger than any budget.

Return of the Living Dead (1985)

Most zombie comedies remain content with just riffing on the genre rather than adding anything substantially new to it. But Return of the Living Dead, in which a bunch of punks have to survive an onslaught of zombies created by toxic gas, pushed many tropes into fame. Not only did it popularize the joke that zombies were after “brains” (the film is full of nibbled skulls), but the zombies are also able to break into a jog when they want to, ridding them of the Frankenstein’s-monster-esque gait that most films saddled them with. As such, Return of the Living Dead plays more like a rejuvenating experience than a parody, and it’s a flurry that many sequels and successors would try to imitate.

Pet Sematary (1989)

“Sometimes dead is better” is advice that could apply to the entire zombie genre, but it takes on some poignancy here as a grieving father tries to bring back his late son with terrifying results. This adaptation of the Stephen King novel leans it out a bit, focusing on the moments that bear the most emotional weight without sacrificing the atmosphere. The outcome isn’t as fondly remembered as other King adaptations like Carrie or The Shining, but using the familiar zombie structure to comment on the universal fear and melancholy over death makes Pet Sematary a thoughtful, lurid affair.

Braindead (1992)

Though the horror boom of the ’70s and ’80s had mostly died out as the ’90s rolled in, you wouldn’t know that from Peter Jackson’s Braindead. His Lord of the Rings films have their fair share of scary sequences, but Braindead reveals another side to the New Zealand director, one that wallows in juvenile humor and over-the-top blood and guts. There was a gory arms race among directors in the new millennium, and one can find Braindead’s grubby fingerprints all over it. If anything, Braindead feels a bit like the end of a zombie era. There would be no way to outdo scenes like the main character using a flipped lawnmower to mangle an entire room of zombies when it came to pure carnage. From here, the genre would need a fresh restart.

28 Days Later (2002)

Danny Boyle’s unflinching zombie thriller is a mix of things — a rebirth of the zombie genre a decade after Braindead, a greatest-hits collection (it’s full of nods to Romero films like Day of the Dead), and an escape from aspects that might seem cartoonish (it tries to stay away from the term “zombie,” a tactic used later by The Walking Dead). The zombies move fast here, so some of the traditional zombie moments, like the inevitable part where everyone is blockaded in a house for a while, don’t really work in 28 Days. Instead, the film makes zombies feel dangerous again, perhaps for the first time since the late ’70s, and 28 Days can be pointed to as the reason why the next two decades were so full of the undead.

Shaun of the Dead (2004)

The magic of Shaun of the Dead relies on its sheer amiability. The story of some friends and family trying to survive a zombie apocalypse is funny, but it also has a lot of heart. That separates it from other zombie comedies that exist on tired satire alone. Even without the jokes, it would work. The buddy main characters, played by Simon Pegg and Nick Frost, are sympathetic underdogs and it ratchets up the tension whenever they are in distress. (Edgar Wright might have been mostly known for comedy then, but he understands his way around an action scene.) In the end, maybe its most profound effect was introducing the wider world to Wright and Pegg, guys who had cut their teeth on British TV and were now about to be launched into the mainstream.

Slither (2006)

This summer, we get to see what director James Gunn has done with Superman, the most famous superhero of all time. Twenty years ago, though, he was a debut director trying his hand at a film about a town being infected by alien parasites. It’s clear that Gunn has been influenced by ’80s films like Return of the Living Dead and Night of the Creeps, as he’s dead set on reviving their blend of gruesome horror and witty dialogue. But Gunn’s secret weapon, one that he’d maintain as his budgets expanded into the nine digits in the Guardian of the Galaxy films, are moments of oddball pathos. Characters might be beyond redemption, but none exist without a heart.

REC (2007)

One of the most popular (and infamous) horror trends of the aughts was the rise of the found-footage movie and, like the effects of a zombie bite, no genre was immune. Thankfully, we got some examples of the blend done well, like REC, which continued the legacy of underappreciated Spanish zombie flicks with a film about a reporter and some firefighters that get trapped in an apartment complex during zombie quarantine. REC is nerve-wracking; it makes full use of the fact that there’s no way out of the cramped corridors and sweaty rooms, thus reducing “fight or flight” to just “fight.” And while it starts to get a little liberally cinematic with its camera work toward the end, for the most part, it maintains its gut-covered cinema-verité stylings.

Pontypool (2008)

In the post–28 Days Later climate, the zombie genre quickly became crowded with forgettable sagas of people running away from made-up extras in alleyways. Pontypool, which doesn’t hide its low budget (most of it is set in a radio station with a few characters), relies mostly on pure cleverness. Its method of zombification isn’t through bites, plague, or voodoo, but rather language, and the verbose set of survivors has to play cat and mouse with their own words if they want to escape with their flesh intact. Tense, with little bits of troubling violence littered throughout, Pontypool isn’t quite a “thinking man’s zombie film,” but it is a film for people who want a zombie film that gives you something to think about.

Dead Snow (2009)

The subgenre of “Nazi zombie” movies is far from empty; even before Dead Snow, we’d gotten flicks like the underrated Shock Waves and the very-much-not-underrated Zombie Lake. Dead Snow, though, bearing a poster that’s as good as the actual film, prides itself on its constant assault of goofy violence. There’s little plot to speak of — characters exist solely to be creatively killed and there are multiple ingenious uses of someone’s intestines. But films like this, ones not destined to make a splash at the general box office, were part of the last hurrah of horror on home video. There, all niches could be represented, even if your particular taste lay in seeing someone attaching a machine gun to a snowmobile.

Zombieland (2009)

Zombieland can’t escape the fact that it’s a product of the late aughts. It’s got a cute Bill Murray–playing-himself cameo and its tagline was “NUT UP OR SHUT UP.” But at only 88 minutes and with an amazingly fun core cast, Zombieland manages to outdo overstuffed zombie outings from around the same time (see: World War Z and the enthusiastically preposterous Resident Evil series). It’s also got heart, making it an outlier to the wider trend of zombie-apocalypse films that focused on just how much humanity the world has lost. Add the stellar practical-effects work — the movie certainly doesn’t skimp on just how much fun it is to see a zombie get dismantled, and you can envision waves of filmmakers taking notes for their own later zombie efforts — and Zombieland manages to be more than a relic.

The Wailing (2016)

At 156 minutes, The Wailing seems to commit the cardinal sin of the zombie film: It’s just too damn long. There are only so many times that we can watch the same folks flee from the undead before we begin to wish they’d just let themselves get bitten and be done with it. But The Wailing, about a mysterious illness/series of possessions in a small Korean town, manages to beat back against the tide of its own running time with its inexorable atmosphere and a story that shifts between cultural fears, familial drama, supernatural delirium, and moments of jarring gruesomeness. The Wailing also absconds from the typical zombie-film operating pattern of allowing survivors to feel more self-assured as they figure things out. The Wailing feels almost clumsily human, a wide-eyed, panicking look at a world gone mad.

Train to Busan (2016)

Released the same year as The Wailing, Train to Busan was proof that South Korea had cornered the market for a while on effective zombie flicks. It couldn’t be more different from Wailing, too — Busan is a cycle of roller-coaster thrill rides, constant movement, and chaotic assaults. But within its well-choreographed sequences of nonstop fighting and fleeing, Busan pulls on our heartstrings with expert efficiency. There’s a reason why it turned the well-bicep’d actor Ma Dong-seok into an international star. He’s the ultimate wife guy here, a mix of everyman gruffness and pro-wrestler technique. No one has ever looked cooler beating a zombie to re-death.

One Cut of the Dead (2017)

It’s hard to describe One Cut of the Dead. The Japanese film contains not only a film within the film, but the behind-the-scenes process of the making of that film which is itself another film within the film. To explain any more than that would be depriving newcomers of perhaps the most refreshing reinvention of the zombie film since the early 2000s. One Cut of the Dead isn’t just a marvel of filmmaking, though it is that. (The first “film within a film” is a 37-minute “single take” sequence that manages to feel completely warranted.) It’s a tribute to low-budget, DIY filmmaking. And what better genre to place it in than zombies, a subject that has seen all manner of cheap triumph, blockbuster exhaustion, and everything in between.

The Sadness (2021)

The Sadness is definitely not everyone’s cup of tea. Once the film begins its snowballing display of depravity, it doesn’t let up until the credits, and what the two 20-something leads experience on their path of trying to reconnect is both violent and grimly perverse. There are few other horror films that commit so heavily to the lurid potential of their storylines, and when that story involves a sudden pandemic that essentially forces each victim to enact their worst urges on the world, you probably know whether this movie is for you or not. But for devotees of uncompromising horror, The Sadness is a gift. You’ll never look at an umbrella the same way again.

MadS (2024)

What does the zombie genre have to offer in 2025? Of course, there are megafranchises like The Walking Dead and The Last of Us, and blockbusters like 28 Years Later, but what new things are being presented? For that, you need to dig a little deeper. MadS (now on Shudder) is a French film that has you wondering if you’re really watching the end of the world or a group of teenagers’ really bad psychedelic trip. In both cases, it’s a great time. The actors commit fully to every deranged tic they’re saddled with, so even long scenes of them wandering through the street, looking for people to terrorize, are gripping. If you measure a zombie film’s worth on just how many dozens of people they can get to snarl in a field somewhere, MadS won’t impress. But it’s what the zombie genre needs right now, unless it wants to be put back into the earth again.

Related

- 8 Great Zombie Comedies (That Aren’t The Dead Don’t Die)

- Which Emo Zombie Movie Is Right for You?

- The Completist’s Guide to Streaming Alex Garland Movies

The zombie is one of the most oversaturated horror symbols of our time, but our appetite for it is seemingly endless.