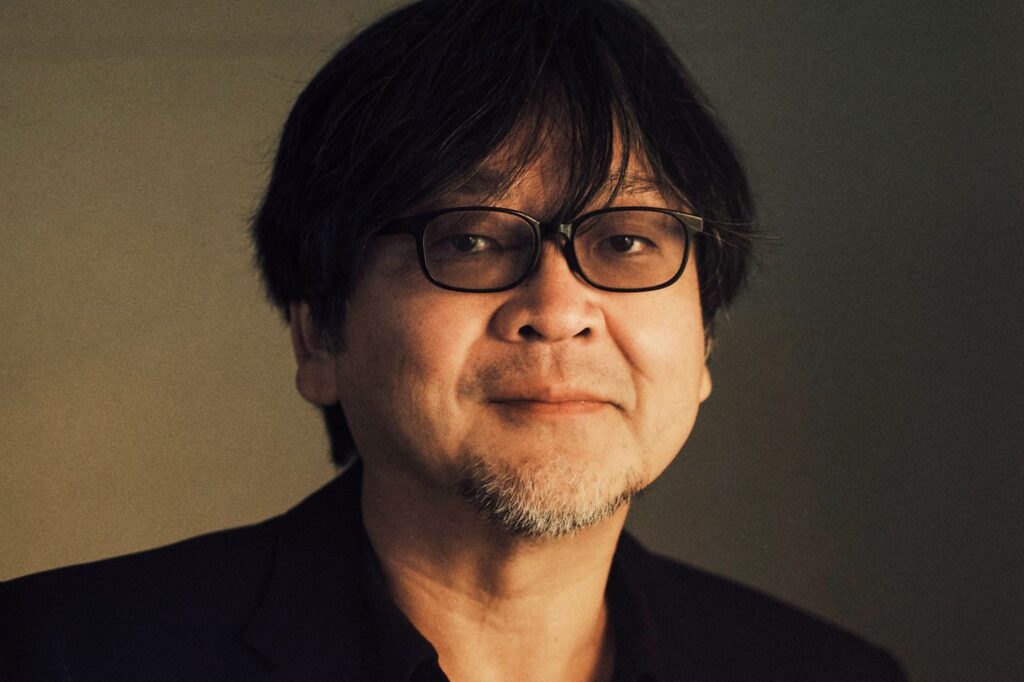

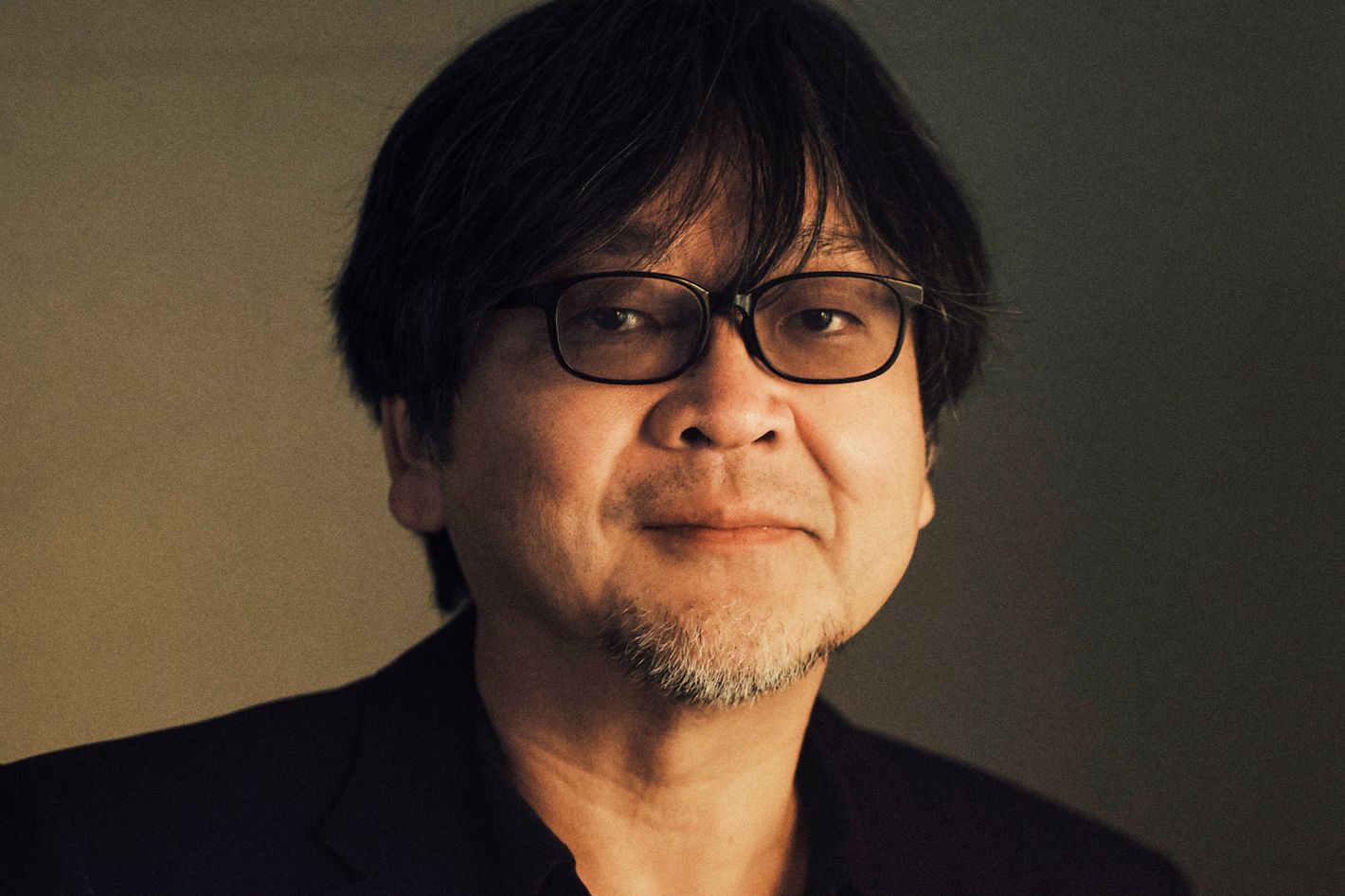

Mamoru Hosoda is troubled by a world where children die. The director and father of two made that concern a driving principle of his new film, Scarlet, a fantastical animated adaptation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet that opens at New York Film Festival next week. In Hosoda’s gender-swapped retelling, a medieval princess watches as her father is publicly executed and usurped, and she swears revenge. The director gives her a conscience and companion in Hijiri, a nurse from present-day Japan who attempts to show her that she deserves a life of peace. Nonetheless, her bloodlust propels her through a liminal purgatory called Otherworld, a desert plane of reality ravaged by war, rife with innocent victims, and haunted by rootless spirits like her.

Like his Japanese filmmaking peer Hayao Miyazaki, Hosoda has found international acclaim by making movies about young heroes, often girls, on the path to adulthood. After signing on as director of Studio Ghibli’s Howl’s Moving Castle and being replaced by Miyazaki himself, Hosoda’s directing career blossomed. His films that followed, including character-driven fantasies like The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, techno-fables like Belle, and slice-of-life family dramas like Wolf Children and the Oscar-nominated Mirai, earned him and his production house, Studio Chizu, the respect of animators and audiences around the world. Scarlet feels like his biggest movie yet, a ruminative war picture that stages medieval battles and pitches its characters through the mortal coil and back.

In the horrific backdrop of Otherworld, Hosoda and Studio Chizu find beauty. Its textures feel tactile and studied, the action of the film is animated crisply and deliberately, and the overall effect of watching the film is uncanny verisimilitude. Otherworld, a home to undead hordes and a lightning-hurling dragon, evokes the colors and landscapes of the real world. The setting underscores Hosoda’s big idea for the film: to represent and abstract human struggles so that audiences can better understand them. “How did people live in tough times in history, and how do we compare it to what’s happening today?” he wonders in a conversation held through a translator. Scarlet was his oblique attempt to answer those questions. “That’s why I’ve looked to classic literature and history, to use it as a lens to view our current state of the world.”

Anime is more popular than ever in the United States. Your profile as a filmmaker has grown, too, with Mirai nominated for an Oscar and your last film, Belle, earning several other awards nominations in the U.S. Did you have about western or American audiences in mind while making Scarlet?

Certainly. I think I first became aware of international audiences 19 years ago, when my film The Girl Who Leapt Through Time was invited to the Busan International Film Festival, to my surprise. That’s when I realized, Wow, there’s a huge audience for anime and my movies outside of Japan. I wouldn’t say it drives my decisions, but it certainly is in my head.

How do your fans in the States respond to your movies differently than those in Japan do?

I don’t know if I really have a full perspective of that, but if I had to put it into words: In Japan, my films are viewed more as an entertainment spectacle. The movie is an experience, a journey for the moviegoers. In international markets, I think I’m funneled into more of this artistic or art-house category, judging from the fact that I’m invited to film festivals like Cannes for Belle and Venice Film Festival for Scarlet. So there might be a slight difference in the perception of my films.

You’ve described Scarlet as inspired by post-COVID geopolitics. That comes through in the fighting and distrust that the protagonists see everywhere in Otherworld. One of the refugee children they meet says she wants “a world where children don’t die.” Were you reacting to specific real-life conflicts?

I know there’s a lot going on right now. This would make for a very direct response if I said one single event, but I don’t really think there is any single event. It’s just this sort of general climate and mood. Right now, conflict is happening more than in most modern eras that we’ve experienced. I don’t want to pick any specific event because this isn’t supposed to be a documentary. It’s supposed to be a kind of throughline about this general animosity, toward a cycle of revenge. It’s a more universal message. How do you escape this vicious cycle? Is it forgiveness? The purpose of the movie is to lead audiences in that direction.

You’re a father, and many of your films follow families and parenthood. Your twist on Hamlet is that the king actually tells his daughter to “forgive” rather than seek revenge. Do you see yourself or your kids in characters like Scarlet, Hijiri, or her father?

I’m the kind of director who looks at experiences close to me. That informs a lot of my creative thinking. I know some directors and filmmakers who can completely shut that out, but in my case, there is a certain cause and effect. I have a son and a daughter. My younger one’s my daughter, and she was the subject of Mirai, for which I thought about what kind of world she’s going to live in. The same was true of Scarlet. She’s 9 right now, but how will the world evolve? How will she be able to navigate it, and how will her generation live? I don’t want her to feel like she’s defeated by this world. It is our responsibility and my desire for these children to live fulfilling lives.

The movie deals with a lot of heavy themes: life, death, the intersection between the two. There’s a lot of fighting. Despite all of that, there are moments of enjoyment like the dance sequence. That is perhaps Scarlet’s hope and her vision of the future. She is chasing revenge, and she values her life less and less, but if you peel all of that back, perhaps her true desire was a world without vengeance.

On Mirai, you actually brought your own kids into Studio Chizu so that the animators could use their movements as references in their animation. So much of Scarlet looks hyperdetailed, often photorealistic, a blend of hand-drawn and CGI. What real-world references did you look at to create the world of the film?

The entire world is searching for this new animated look. If you were to rewind the clock, you would be limited to certain styles of 2-D hand-drawn animation or 3-D texture. But I think right now we’re all searching for a new form of expression. Part of the reason for that, perhaps, is this coming of artificial intelligence. I think AI can do a great job of copying certain styles. But with the struggle that animators and directors go through, perhaps we all have to ask the question, What is that effort for now? So I think a lot of us are trying to pursue some new visual language that both hasn’t been done before but also can’t be copied by AI.

In our case, we observe our surroundings, whether it’s movements or visuals. In Scarlet, there’s only one scene, I want to say, for which we used motion-capture: the dancing sequence. Everything else was hand-animated CG. The animators had to observe their surroundings, observe people move, and then subtract and abstract the key movements that onscreen deliver some kind of purpose or nuance. That’s what makes animation so attractive.

Let’s stay on AI for a moment. How do you feel about the growing prevalence of generative AI right now? Do you see possibilities in the technology?

We make animation from — I don’t know if I want to say thin air, but basically ideas translated through people. They manifest as visual expressions that move, that can deliver and carry some kind of message or feeling to audiences. And AI is greatly bridging that gap of going from idea to visual in ways that we’ve never seen any tool do in the past. I had the chance to chat at the Toronto International Film Festival with Domee Shi, who directed Turning Red at Pixar. When we were talking, she said, “If AI is happening, and it’s something that we can’t avoid, how do we face it? And how do we find a way to coexist with it yet still express our individuality?”

In our chat, we thought that perhaps a lot of people are feeling the same way. Writers, lawyers, translators, interpreters, anyone whose intellectual, critical-thinking job can be bridged or at least greatly closed by AI — animators are no different. We’re going to come to a crossroads of: How do we find a way to coexist with this tool that can do so much in ways that we didn’t even expect? I don’t really have an answer, but I think the first task is to understand where we place the individuality of creators.

Your last film to compete for an Oscar was Mirai. It’s still not common for anime films to win that award. For Japanese animation, only Hayao Miyazaki has won — twice. Do you care about your films winning one?

Obviously there is a desire to win something like that. But that’s not why we make movies. First and foremost, the goal should always be to make a good film. Creators will always want to reach through the screen and shake their audience’s hand and relate through film. Perhaps going for and winning an Oscar is one way to do that with more people, but that’s never the goal. There is also something attractive in exploring the unknown. Perhaps that challenge might yield something great, or it might yield catastrophic failure. You never know.

I actually wanted to ask you about Miyazaki and what you thought of him. You were quoted by the Agence France-Presse as saying the following at Cannes in 2021:

“I will not name him, but there is a great master of animation who always takes a young woman as his heroine. And to be frank, I think he does it because he does not have confidence in himself as a man. This veneration of young women really disturbs me and I do not want to be a part of it.”

I wanted to ask: What did you mean by this? Several news organizations reported you were talking about Miyazaki. Do you stand by the quote? How do you feel about it now?

To be frank, I don’t really recall saying something like that or to that effect. But the way you described it, it would be hard to think of anyone besides that person, in terms of whom it’s referring to. But I don’t know if it was a misunderstanding or a misquote or a mistranslation or if I did say it and just don’t recall. But yeah, I’m not sure what to say.

I don’t think that sounds like me, in the sense that I don’t try to put down or have an ego contest with other creators. I think that kind of negativity I try to avoid. So perhaps the author of the article maybe used me as a mouthpiece and interpreted something I said in a different way and rewrote it. I don’t know. I don’t really see myself in direct competition with Miyazaki either. I see us more as coexisting in a sense of trying to do our own thing and express our own ideas and visuals through the medium of animation. I don’t know if that’s the answer you’re looking for.

I’m not looking for any specific answer. I just wanted to give you the opportunity to revisit and follow up on the quote, because it had been out there.

With regards to Miyazaki, there’s certainly a lot of praise and a lot of it is deserved. But there’s some that goes so extreme, that he’s a god, he’s amazing, he transcends all this. And perhaps I think that level of comparison and using that type of language to compare and then criticize other directors is, for me, a little questionable. I think there are a lot of projects that deserve a lot of respect, and some opinions on him and what he’s done just seem so extreme to me. And I think an extreme way of thinking like that is in some ways boring, because there are so many more amazing talents and directors and creators out there. In my case, I believe that diversity is what creates a lot of value in our industry and gives audiences different experiences and flavors of life.

More From the New York Film Festival

The Scarlet director on respecting his predecessors while finding new talent to champion too.