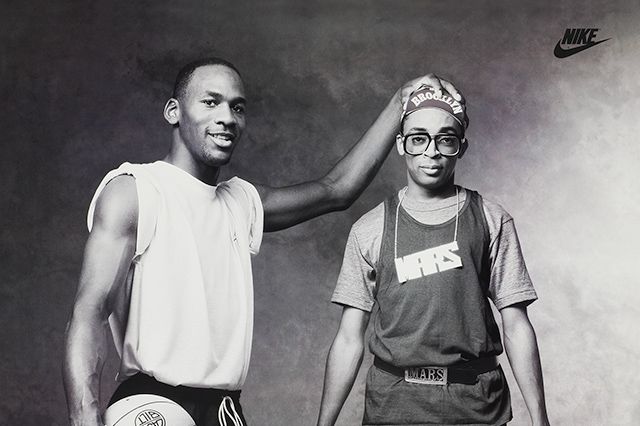

Over Spike Lee’s more than 40 years of directing feature films — from his indie breakout She’s Gotta Have It (1986) to his epic Hollywood biopic Malcolm X (1992) to his polemical Hurricane Katrina documentary When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts (2006) — he has earned a reputation as a provocateur and a savvy self-promoter. His “joints,” as the Brooklyn-bred auteur brands his movies, have sparked ludicrous fears of rioting (Do the Right Thing), unsettled audience notions about race and sex (Jungle Fever), and landed him in blockbuster Nike ads alongside Michael Jordan (“Money, it’s gotta be the shoes!”). His new movie, Highest 2 Lowest, aspires to no such distinction. Lee’s lively reimagining of Akira Kurosawa’s 1963 crime drama High and Low just seeks to stage an entertaining morality play. But this is Spike Lee we’re talking about, which means his dramatization of a kidnapping plot involving a high-flying record executive, played by Denzel Washington, and a destitute superfan (A$AP Rocky) seems destined to be read as something more — whether the director intends it to or not. Sitting in the Fort Greene office of his production company, 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks, surrounded by a kaleidoscope of global cinema memorabilia, framed vinyl records, and New York Knicks artifacts, Lee, 68, is alternately as charming and prickly as ever.

I’m a fan of the original High and Low, so I was excited to see your interpretation.

I want to say this right here, from the jump: This is not a remake. This is a reinterpretation. I was introduced to Kurosawa when I was doing NYU graduate film school. And a lot of people don’t know this, but the thesis of She’s Gotta Have It came from Rashomon. In Rashomon, there’s a rape and the audience is left there questioning, “Who’s telling the truth?” So I just hijacked that shit.

What has kept you returning to Kurosawa?

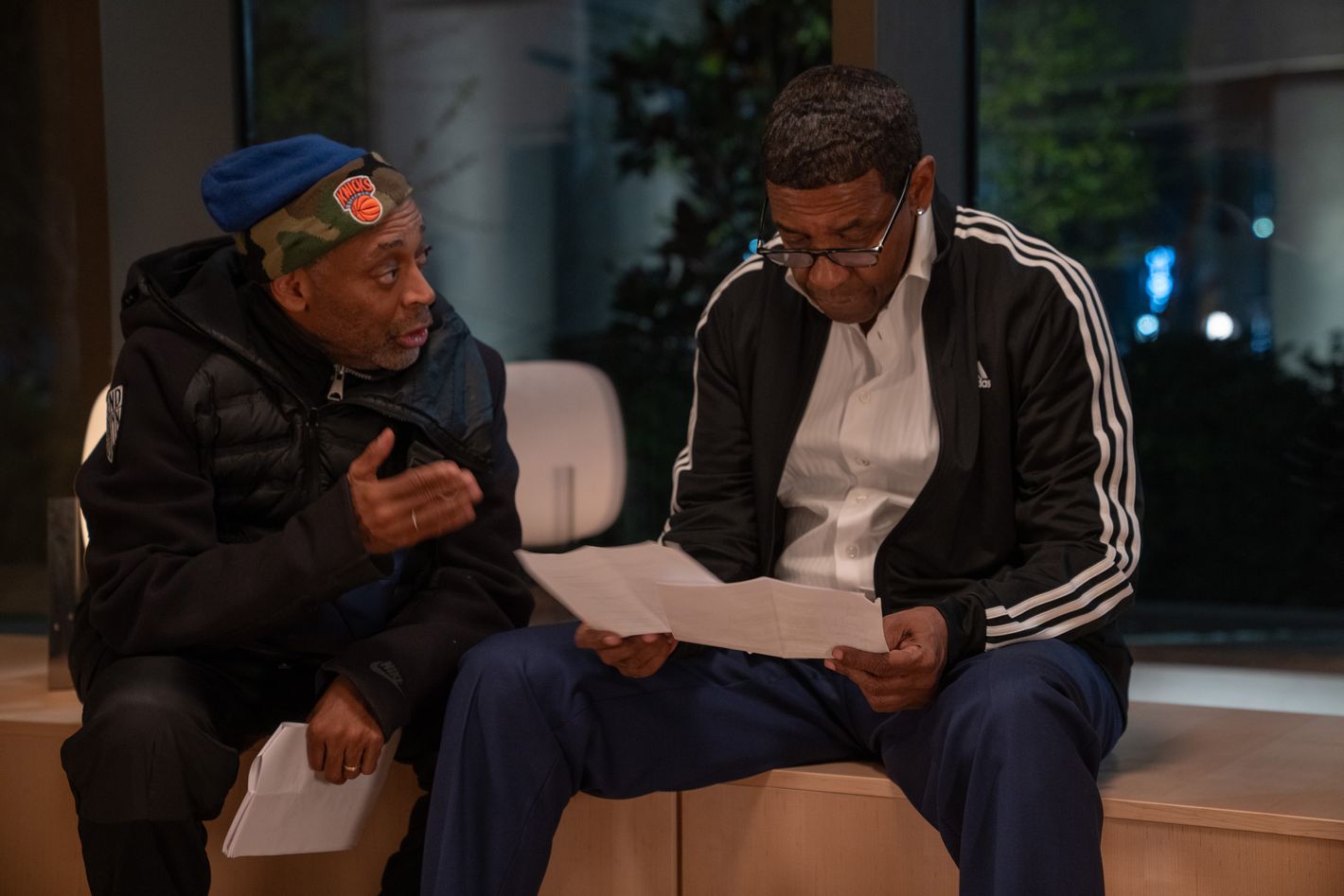

Here’s the thing: They’ve been trying to make this film for — Scott Rudin was trying to make it. So Denzel came to me and said, “Yo, let’s go.” We did not know Inside Man was 19 years ago. The way we work, it was like it had wrapped yesterday.

Was it hard to get funding for Highest 2 Lowest given the economic climate in Hollywood?

Nah. It was Denzel Washington! When Denzel came to me ready to go … Money was not a problem, boss.

There’s been talk about Denzel wanting to retire soon.

Don’t believe the hype. Mr. Denzel Washington will hang them up when he wants to hang them up.

Does Highest 2 Lowest feel like a fitting potential capstone to your partnership?

It’s historical. It’s monumental. “D and Lee.” Bleek Gilliam in Mo’ Better Blues. Malcolm in Malcolm X. Jake Shuttlesworth in He Got Game. And Keith Frazier for Inside Man. No disrespect to anybody else, but for me, Denzel’s the greatest living actor. And that’s just my opinion, you know? You ask Scorsese, he’s going to say De Niro. Francis Ford Coppola would probably say Brando.

You cast A$AP Rocky in this movie opposite Denzel, and he really holds his own.

For years, people have said that A$AP looks like Denzel’s son. People on Instagram were like, “Spike, why don’t you cast Rocky?” Before this even came up. And, you know, Rocky ain’t give no quarter. Toe to toe. He’s an actor. He has presence, and he’s serious, too. As serious about his acting as his music.

The salsa musician Eddie Palmieri, who performs in the movie, recently died. I was sorry to hear that.

A big, big blow. He’s one of the greats. Eddie had been sick, so I sent flowers to the hospital, but there was a mix-up, so the flowers went to his home. And that’s where he passed away.

I was so sorry to hear that. Now you have the New York premiere of the film, where Eddie’s son is speaking, then it goes to Apple TV+ three weeks after that. How do you feel about the short theatrical window?

Well, you have to speak to Apple and A24 for that decision. If it was my choice, I would not have made that decision. And folks ain’t happy either. Some of these things I had no control of, and the people that run things had a different plan, but you go to social media and people are letting their feelings be known. I’ll leave it at that. Apple+ financed the film, so they’re calling the shots, and I think it’s great that people like streamers. I would have liked a longer theatrical release.

Are the themes in this movie in any way a reflection of your own preoccupations? It’s partly about an older artist who is trying to rediscover a sense of joy and love in his craft.

Nah, that character has nothing to do with me. Shoot, when I’m working, I don’t need an alarm clock to get me up. I’m ready. Because I’m doing what I love.

Which contemporary filmmakers excite you the most?

If you’re talking about the major leagues, Ryan Coogler. I just happened to be in L.A., and Ryan called me and said, “Are you around? We’re getting ready to do a Sinners proof on Imax.” So I went, and I was sitting next to Ryan and his beautiful wife, Zinzi. And when that — they got a name for that musical scene yet? That shit fucked me up. That scene lifted the movie to the stratosphere. He’s an amazing filmmaker.

You’ve been a longtime admirer of Scorsese as well.

Well, you know, we’re good friends, too. Oh, man, we get together and we start talking about movies, somebody should record us talking.

From very early on in your career, you’ve had what has felt like an antagonistic relationship to Hollywood. Now you’re an Oscar winner and a juror on all these big film festivals. What’s that shift been like?

No, it’s good. I never really thought of myself as an outsider. Well, in some ways I am, because I’m not in L.A.

Being a filmmaker in New York has changed a lot, too.

I mean, now we got permits. Before, we just did shit. But no, it’s great when you can work where you live. And I have a great crew. People who have worked with me since Do the Right Thing. And their kids are working on it now. So this is the base, right here, 40 Acres, the People’s Republic of Brooklyn.

You were born in Atlanta, right?

Grady Hospital. And then got the hell up out of there. What happened was that my father moved to Chicago because that’s where the jazz scene was, and then moved to New York.

You also played music as a kid.

I played recorder and violin. Not good, either. I didn’t have the discipline to take lessons. Man, it was Brooklyn. We’d just run up and down the street, stickball, handball. I mean, that was it for me.

Your parents are both artists — your mom was an art and literature teacher. Where did your political sensibilities come from?

That’s just the family. Just very pro-Black.

I read an L.A. Times piece from when Crooklyn came out in 1994, and I understand that your dad, who was struggling at the time and asked to borrow money from you, which you refused, did not respond well to it.

Nah, I mean, look, he was very proud of not just me, of us, what all his children were doing. But my love of cinema came from my mother. My father hated movies, so I was my mother’s date, since I’m the oldest. She loved Sean Connery.

You’ve said that some of the first films that made you fall in love with movies as a kid were Sean Connery’s 007 movies. Do you have any interest in directing one, and would you like to see a Black Bond?

Barbara Broccoli didn’t want to put me down [to direct any of the films]. I mentioned it to her. She knows I would take a meeting. I don’t know who I’d like to see, but it would be interesting to see if they do a Black Bond.

1977 was an especially formative year in your development as a filmmaker.

My mother had just died. I came back to New York from Morehouse College in Atlanta. Just finished my sophomore year. Summer of 1977, New York City was broke so there were no summer jobs. I went to see a friend of mine, Vietta Johnson, who lived at the other side of Fort Greene Park, I went to see her. And that day changed my life. She was studying for some test; she was always smart. She went to Stuyvesant High School, Princeton undergrad, and Harvard med school. Went to her house, and in the living room was a box. I said, “What’s in the box?” “It’s a Super 8 camera,” she said. “You can have it.”

Now I had something to do. I spent the whole summer documenting that infamous summer. When the blackout happened, I was filming all my fellow sisters and brothers, and the looting was crazy. I later told a teacher at Clark Atlanta University, across from Morehouse, Dr. Herb Eichelberger, about the stuff I had shot. He says, “You’re making a documentary.” He took an interest in me. On days when he wasn’t even teaching, he would come to school and open up the lab so I could work on this short called Last Hustle in Brooklyn. Once I graduated from Morehouse, I applied to the top-three film schools in the world: USC, AFI, and NYU. For the first two, you had to get an astronomical store on a GRE, and it’s been proven that those tests are biased against people of color. But thank God, thank you Jesus, you didn’t have to take a GRE to get into NYU. Just submit a great portfolio.

What was it like to have such a concentration of talent at NYU at that time? You, Ernest Dickerson, Ang Lee, Jim Jarmusch.

Jim was our hero. We got to NYU, but we didn’t go with Scorsese, we didn’t go with Oliver Stone. We’re behind them. I worked in the equipment room. So I checked out equipment to Jim Jarmusch. And when Stranger Than Paradise hit, oh, we was so happy. We was just happy for him, for us, because now, we saw, he laid out the plan. Everything he did for Stranger, I did for She’s Gotta Have It. But I do remember that while I was at NYU, Scorsese showed a film and held a Q&A and I could tell he was ready to get the fuck out of there. But I was the last person, and we spoke for like 20 minutes. He didn’t have to. And he remembered me, too, that conversation. So we’ve been very close.

Pretty early on, you became the face of Black film in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but obviously you had a lot of incredible contemporaries.

Oh, of course. Me and John Singleton were close. And he left us way too young. He was a cinephile, you know, so we talked about films all the time.

You also acted in a lot of your earlier films. What caused you to stop, and would you ever go back to it?

I’m not going to say never, but those were roles I specifically wrote for myself. I don’t need to be in front of the camera, styling and profiling. She’s Gotta Have It happened because we had no money to pay somebody to act and then my character Mars Blackmon turned into a lucrative relationship that sent Nike into the stratosphere. The pairing of Mars Blackmon and Michael Jordan changed the whole sneaker game. It was two gentlemen from an advertisement agency called Wieden+Kennedy who saw the film, and they went to Michael, who had not seen She’s Gotta Have It. He didn’t know who the fuck I was. It wasn’t until the All-Star weekend in Toronto that I finally got up the courage to ask Mike, “Why did you do it when you didn’t know who I was?” He looked at me and said, “Motherfucker, you wearing my shoes.”

What do you think made Mars Blackmon such an appealing cross-promotional figure — a character who could sell Jordans and provide a big boost for your profile as a filmmaker?

I mean at one point — before Do the Right Thing — more people knew me for the commercials than my movies. Mars was funny. And he played the foil to the greatest. It was just a juxtaposition: Why is Mike with Mars, why is Mars with Mike? I have a big regret, though. I had a chance to take the cash or Nike stock. Whew. Who knew?

Do you have any hard lines you won’t cross when it comes to what kind of products you’re willing to promote? There was that ad you did a few years ago for the Coin Cloud ATM, where you claimed cryptocurrency was a way for people to overcome oppression.

I don’t know if it was that deep. But I will say this: That stuff’s real now. I mean, they’re writing all types of laws making it … you know. That stuff, you got to get in it early.

A less known part of your legacy is you forced the Teamsters to integrate — they didn’t have any Black drivers when you were making Do the Right Thing.

Racist motherfuckers. I had a meeting with them, said, “Yo, we got to have some brothers.” I said, “We don’t have some Black people up in here; the Fruit of Islam can drive trucks, and you don’t want that.” Now they have us brothers driving the trucks. And today, a whole lot of brothers come up to me and say, “Spike, you know you got me into the union.”

You’re known to be a very persistent and persuasive person. What’s your secret to getting people to give you money?

Well, it’s belief in me. My friend Earl Smith and I went to John Dewey High School together. His mother dies, he gets a check for insurance and says, “Take this money.” I didn’t even ask. He offered it. And that’s a lot of pressure. He invested that in my first feature film, She’s Gotta Have It. The best move he ever made — now he has two brownstones in Fort Greene. He’s still getting a check today. The film came out in 1986. Thank you, Earl.

The stakes were a little higher on Malcolm.

For Malcolm X, man, I was begging. Warner Bros. fired all the people in postproduction who were editing, and I was at my wits end. I’d put a million dollars of my salary into the budget; I was broke. Thank God, you know, sisters and brothers came through. In doing this film, I had become a student of Malcolm. I had to. And when I was in this funk where the whole thing was suspended, I had a lot of time to think. And Malcolm always talked about self-reliance, self- determination, and finally that clicked in my mind. Like, “I know some rich Black folks.” And we continued the work and on Malcolm X’s birthday we had a press conference at Schomburg Library in Harlem. I told these prominent, beautiful Black folks who had money that this could not be a tax write-off; it’s not an investment in the film per se to get a return. The only way this works is if it’s a gift. And Bill Cosby was the first one I went to. The last two were Magic and Michael. I was very strategic. And so Michael Jordan was the last person. I just let it slip to Michael how much Magic gave. And so, you know, see now, one of Michael’s nicknames is Money. “What? Magic gave how much? I got it, Spike.” And once that happened, then Warner Bros. hired everybody back to finish the film. That’s a true story.

What do you think would have been missing from that film had Norman Jewison, who was originally hired as the director, or any other white filmmaker tried to tackle it?

I have full respect for Norman Jewison. Great director, worked with Denzel on The Hurricane. I just felt that, if that film’s going to be made, I was going to direct it. I was qualified, I was determined, and I was not messing around. So Norman and I, we had a sit-down, and I explained to him why I felt the way I felt. And he understood it and he bowed out gracefully, which he did not have to do. So I always give respect to him, Mr. Jewison, because he ain’t have to do that.

Talk to me about how you and Denzel developed Malcolm as a character, as opposed to just an imitation?

Well, here’s the thing: Denzel did an Off Broadway show in 1981 called When the Chickens Came Home to Roost where he played Malcolm. Then he had a year before we could shoot. Biopics, they can be tricky. It’s not just imitating the voice or clothes or the look or makeup. That’s surface. Denzel put in the work, and he understood that the only way this could work is the spirit of Malcolm has to come into his body, into his self. You got to make yourself vulnerable for that to happen. And he had to dig deeper than that because he’s playing four or five Malcolms. Detroit Red, El Hajj Malik, which was the last one. Denzel put in the work. There would be scenes where we would pinch ourselves: “Is that Denzel or was that Malcolm?” That’s how deep that shit was. I mean, I know it might not sound like the right word, but he was possessed. And I’m not talking about evil, I’m just saying the spirit of Malcolm was in him.

Samuel L. Jackson was supposed to be featured in Malcolm X after his breakout performance in your previous film, Jungle Fever, but he left over a money dispute, which caused a rift in your relationship.

Me and Sam are great. I’m not going back in time. We’re cool, we love each other, our wives … We’re tight. If Sam had a problem with me, I would never be able to do all those Capital One commercials. End of discussion.

What was it like having him give you the Oscar for BlacKKKlansman?

You see me leap into his arms? Man, there’s nothing but love, me and Sam. L-O-V-E.

I don’t see your Oscar statuette in your office. But I see the Knicks flag.

Hold up, my brother. It’s the 1970 NBA Championship banner that hung from Madison Square Garden. May 8, 1970. Game seven. Willis Reed dragged his leg out on the court. I was there. Thirteen years old. Don’t get it twisted.

One thing that’s amazing about these past couple NBA seasons is the resurgence of this Knicks-Pacers rivalry you were such a big part of in the ’90s.

Do you know last year I got inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame as a fan?

There you go. And even the iconography is back with Pacers point guard Tyrese Haliburton doing the choke sign that Reggie Miller did to you during game five of the 1994 Eastern Conference Finals.

There’s nothing but love between me and Reggie. We buried that shit a long time ago. And I don’t want to say nothing about Haliburton, who tore his Achilles in the NBA Finals against the Oklahoma City Thunder, but I don’t think anyone’s going to do this [choke sign] anymore. I don’t wish any player to get hurt. Never. That’s out of bounds. But injuries are a big part of sports. And there are some big injuries ahead of this upcoming season — two key players, Haliburton from Indiana and Jayson Tatum from the Boston Celtics. So maybe this is our year. And if … when we win this ring, the NYPD are hoping that it happens on the road. Because if it’s a home game, you better call the Air Force, the Marines, Coast Guard, Army. It’s going to be like the biggest New Year’s Eve celebration.

New York sports heroes are obviously very important to you. You’ve been trying to tell Joe Louis’s story for a really long time. What’s the latest?

I co-wrote a script with Budd Schulberg. I promised Budd my brother on his deathbed that we’re going to get this film made, and I will fulfill that promise. Budd’s in the Boxing Hall of Fame as a writer. So just to sit down with him over many hours over several years and — I mean, his storytelling was amazing. The thing he told me that resonated is, “People all around the world felt that the winner of the second fight [between Louis and German champion Max Schmeling in 1938] would determine the outcome of World War II.” That’s why FDR summoned Joe Louis to the White House. That’s why Schmeling was summoned to the headquarters with Hitler and Goebbels. That’s how big it was.

On the topic of sports and politics, your next project was supposed to be a Colin Kaepernick documentary.

That’s not coming out.

At all?

All I can tell you, my brother, is it’s not coming out. Let me give you a Spanish word: Nada. N-A-D-A. Let me give you a Brooklyn word. N-U-T-T-I-N. Nuttin’. Reach out to ESPN or Colin Kaepernick. That’s all I can contractually say.

How do you feel about it?

Look at my face. [Lee makes a very sad facial expression.] We worked over a year on that.

That’s a huge shame. Dream projects aside, do you have a favorite film of yours?

Well, I think the one that was the hardest to make is the one that we had the most riding on, and that’s Malcolm. We knew there would be consequences.

Any that you feel were underappreciated in their time?

25th Hour is more celebrated now than when it came out. This is one of my favorite scenes.

Interviewer’s note: At this point, Lee pulls out his iPhone and plays a five-minute clip of the scene where Monty Brogan, Edward Norton’s character in 25th Hour, rants bitterly and profanely about the ethnic and social groups that make up New York City.

Why is that one of your favorite scenes?

That’s New York City. But in the history of cinema, there are many, many films that when they came out were not appreciated. I’ve got an example too, right now: Budd Schulberg, Elia Kazan. They have a film On the Waterfront. Won many Oscars, considered to be one of the greatest. Their next film together, Faces in the Crowd, bombed. Billy Wilder, Sunset Boulevard, a great film, many awards. The next film bombed, Ace in the Hole. And now those films are celebrated. If it could happen to Billy Wilder, Elia Kazan, you know it can happen to me.

One of the things that comes up often in criticism of your movies is that the social commentary is very heavy-handed, as opposed to more oblique or using devices that make it more subtle.

Like Driving-motherfucking-Miss Daisy? That’s what you want? Look, I make the films I fucking want to make, and I’m not coming up with the Driving Miss Daisy, Green Book approach. End of that answer. That’s not me.

How do you deal with collaborators you’ve worked with who later express views you may find reprehensible? I’m thinking of Michael Rapaport, who has recently come out as a very overt anti-Muslim pundit. Is it something you feel moved to address with them?

Michael Rapaport was not doing that when we did Bamboozled; he was not on the radio or saying that stuff that he’s saying. So I have no comment about that. That was not the Michael Rapaport I cast when we did Bamboozled. And I would not use that word “collaborator.” He was an actor. He auditioned and got the part.

The conflict in Gaza is an obvious third rail in Hollywood right now. When Mo’ Better Blues came out, you were accused of antisemitism because two characters in the film, Jewish record executives who exploit the Black musician characters, were seen as negative stereotypes. How did your experience with Mo’ Better Blues impact how you think about antisemitism accusations, especially when some pro-Israel groups call critics of Israel’s politics antisemitic?

Let me tell the story. My late lawyer, a great, great guy who was Jewish, his name was Arthur Klein, called me up and said, “Spike, I’m not speaking to you as a lawyer. I’m speaking to you as a friend. If you do not write an op-ed piece for the New York Times saying you’re not antisemitic, you’ll never, ever, work in Hollywood again.” And he said it more than once so I’d understand the gravity of what he was saying. It’s not the same level as the Gaza discussion; I’m not comparing them. But that’s the game. The idea that Moe and Josh Flatbush, played by John and Nick Turturro, were supposedly antisemitic characters — like in the history of the music business there was never a situation where someone who was Jewish exploited Black musicians?

And I’ll leave it at this: I just find it insane that if you speak about what’s happening in Gaza, if you speak about young children starving to death, that makes you antisemitic. Those pictures that are going around the world now of starvation — it’s a horrible, horrible situation there. I don’t know how it makes you antisemitic if you say something about what’s happened in Gaza.

Your films deal bluntly with other volatile social issues. Given the response to Do the Right Thing at the time of its release — critics in this magazine feared that it would provoke actual riots — how do you think about the resurgent role of rioting in American politics recently?

I’m not answering that question. I’m tired of … Do you know how many times I’ve been asked about Mookie throwing the motherfucking garbage can through the window? What year is this now? It’s 2025.

Sure, but the salience of riots has obviously risen following the unrest of 2020 and January 6. I’m wondering if you think differently about them now, since, like you said, Do the Right Thing came out a long time ago.

I’m not talking about riots. If I had a dollar for every time someone asked me about Mookie …

Just to be clear, that’s not the question I’m asking.

You know what? Let’s talk about Highest 2 Lowest. We can do that. You have me talking about me being antisemitic and now you’re talking about riots, and I’m not doing that.

With all due respect, a quality that usually sets you apart as a filmmaker is that you’re usually not only concerned with whether people enjoy your movies but with the real-world impact your movies have, and how they reflect real-world issues that aren’t traditionally addressed onscreen. Racism, classism, inequality. The dynamic between A$AP Rocky’s character and Denzel’s character is very much a class dynamic. Which is why I have these questions about how your work relates to the real world, including your views about New York, inequality, a mayoral election that’s dealing with these economic divides that are a theme of your movie. This is all relevant.

Well, this film’s not going to play a role in who will be the next mayor of New York City. Do the Right Thing played a role. But this film’s not. This film’s not that. This whole mayoral-candidate thing happened after we were shooting. I didn’t even think about it. This is not an original screenplay. It was a book first written by Ed McBain, an American novelist, screenwriter, TV writer. And it was adapted by Akira Kurosawa. So that was not in my thinking. This film for me is about morals and scruples and what people will do or won’t do for money. So you want to make that a political statement, you can, but for me, that’s not a political statement.

How do you hope audiences respond to Highest 2 Lowest and its social themes?

There’s not a filmmaker alive or a novelist or a singer or whatever who doesn’t hope that their next thing is accepted well by the audience. I mean, that’s elementary. You make a film and you hope that people respond to it. Sometimes they do, sometimes they don’t. Just move on to the next. I don’t go in, getting ready to do a film, saying, They’re not going to like this one. Or This one’s going to be a bomb. I keep it moving. I’ve been doing that since 1986 with She’s Gotta Have It. I’m not going to sit in the corner and cry boo-hoo. Onto the next. Onto the next.

More Conversations

A charming, occasionally contentious interview with Spike Lee as he sounds off on Highest 2 Lowest’s short theatrical release, among other things.