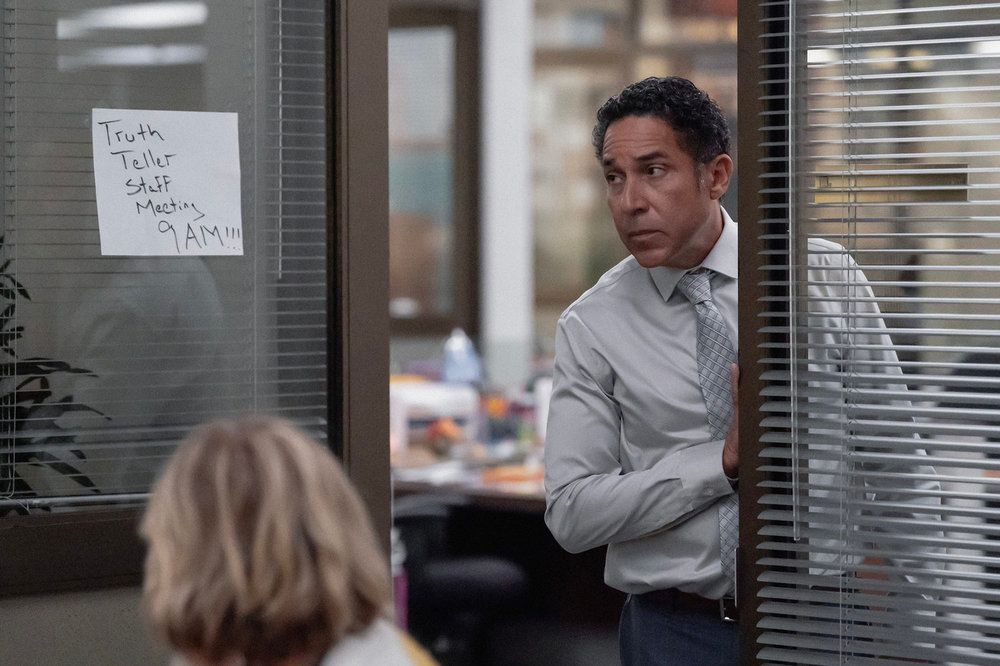

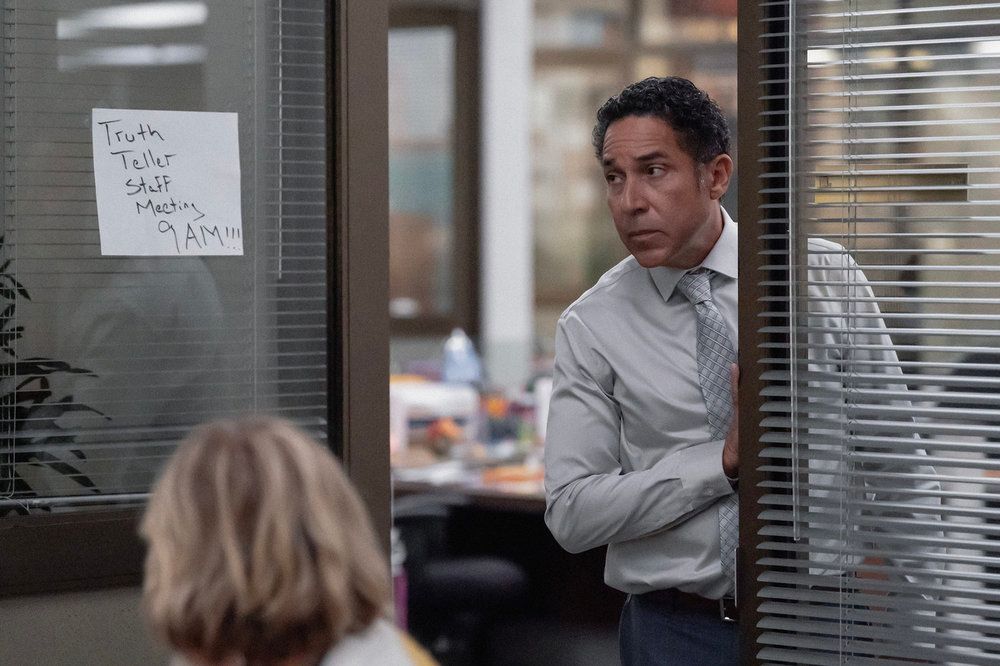

Attempting to spinoff a new show from a long-running, much-rewatched, and still-beloved series like The Office would come with a lot of baggage in any context. But The Paper, the new series from Office co-creator Greg Daniels and comedy veteran Michael Koman, arrives freighted with the baggage of an entire sitcom movement. The Office stands as one of the most influential shows of the past 20 years, popularizing not just its U.K. predecessor’s original mockumentary format but a whole style of post-millennial workplace comedy that’s branched out to the likes of Parks and Recreation, Brooklyn Nine-Nine, Superstore, and St. Denis Medical, among others. If it was difficult to watch any of those shows without thinking of The Office, at least at first, The Paper makes that task intentionally impossible. It literally features Oscar from The Office in a new job, fussing over another documentary crew showing up at his workplace to follow the (maybe) revitalization of the Toledo Truth Teller, a local Ohio newspaper that’s fallen into clickbait-era, post-print disrepair.

Oscar isn’t the star of The Paper, though; he remains, as ever, a clutch supporting player. He’s the only major cast member of The Office to literally appear, although Stanley fields a cute offscreen phone call at one point, while minor character Bob Vance (husband of Phyllis) pops up in the pilot. (Deeper into the season and further afield, someone does, sigh, quote Michael Scott.) But some major Office players linger in spirit as these new characters are developed across The Paper’s first ten episodes. (A second season has already been ordered.)

Mapping old characters onto new ones can be reductive, sure, but it can also be instructive when charting a sitcom’s evolution. Recall, for example, how Amy Poehler’s Leslie Knope was originally written toward Michael Scott–style foot-in-mouth bumbling, and how Parks and Rec improved immeasurably as we saw the writers figure out, as if in real time, a stronger vision for her nerdily intense local-government idealism. As Office alumni branched out, copies begat copies. Brooklyn Nine-Nine, created by Michael Schur (who worked on The Office and co-created Parks and Recreation with Daniels) and Dan Goor (a Parks staffer), mapped even closer onto Parks and Rec characters: Leslie Knope onto try-hard Amy Santiago, Ron Swanson onto the stoic Raymond Holt, Jerry mutated and then split between Hitchcock and Scully. The performances can take those characterizations elsewhere, as was certainly the case with the great Andre Braugher as Holt; they can also stagnate in a watering-down of a superior original formula. (Charming as the show is, I wouldn’t entertain any thought that Brooklyn Nine-Nine materially improved upon The Office or Parks and Rec.)

So as polite as it might be to receive The Paper as an entirely separate operation from The Office, a tour through its first season reveals a particular set of strengths and weaknesses stemming from the origins that it’s counting on to get some immediate curiosity streams. Let’s sort through where these characters start and whether they’re able to land outside the shadows of their obvious models.

(Warning: Spoilers for the first season of The Paper abound.)

The New Michael Scott(s)

One of the most disorienting moves The Paper makes right off the bat is to provide two different Michael Scott figures — neither of whom serve as the lead character the way Steve Carell’s Michael did. The latter is probably a smart decision. While Michael eventually became a surprisingly well-rounded and (overly?) sympathetic character, he also provided opportunities to satirize middle-manager insecurities and petty office politics. There was probably plenty of that to rib in the heyday of local newspapers, but right now, placing a buffoon in charge just seems like kicking an industry in the ribs as it struggles to its feet. So while new editor-in-chief Ned Sampson (Domhnall Gleeson) pulls some classic Michael Scott moves — abruptly calling awkward meetings, pretending to be able to take a joke while actually being easily wounded — he’s more of a Leslie Knope–coded tunnel-vision idealist than a World’s Best/Worst Boss.

Those wacky responsibilities are instead divvied up between Esmeralda Grand (Sabrina Impacciatore), the managing editor who has been acting as interim editor-in-chief before Ned’s hiring, and Ken Davies (Tim Key), an exec for Enervate, the paper’s parent company, which makes most of its money selling toilet tissue. Ken is a more conniving, traditionally corporate toady than Michael Scott, but his lack of genuine management skill and the precisely British performance from Key (recently of the sweet-natured film The Ballad of Wallis Island) bring to mind both Michael and Ricky Gervais’s David Brent from the original U.K. version of The Office. Esmeralda, meanwhile, has Michael Scott’s vanity, desire for attention, and overall cluelessness; we quickly learn she’s been larding the Truth Teller site with celeb-focused clickbait.

The rapid introduction of these characters works against the pilot — we’re meeting a boss figure, then another sort-of boss below him, and then the new boss who will supplant her and create some friction. (The paper’s employees are similarly adrift; they formally work for Softies, the toilet-paper company also owned by Enervate, but some of them volunteer to carve out time to work on the revitalized newspaper.) The org chart becomes clearer as the season progresses, but that also involves both Ken and Esmeralda’s subplots drifting away from the main action. Ken is a more marginal figure by design, though his British cringe humor never stops feeling somewhat at odds with the show’s small-city, Midwest setting. Same goes for Esmeralda’s decidedly different, Italian-accented style: The sorta-villains of this Toledo-set story are both somehow overtly European.

Esmeralda seems clearly intended as an instant fan favorite, a go-to source of big, broad laughs who somehow deepens with every new quirk. Impacciatore throws herself into the performance, emphasizing movement and gesture in a comedy style that often defaults to attempted stillness. It’s skillful; it’s also a lot. Though she begins the season actively trying to undermine Ned and maintain the paper’s clickbait-friendly status quo, she’s too goofy to remain a full antagonist and too big to relegate to a minor character. This results in the show’s second-billed star hanging out in the foreground as if dealing with a fourth-season reshuffle, not the essential premise of the series. Not everything in The Paper needs to stick to news-gathering and reporting, which by nature are not always entertaining or plot-sustaining activities. But why, eight episodes into the season, are we seeing a subplot where Esmeralda rampages through an audition for a toilet-paper ad, hoping to stage-parent her son (and maybe herself) into the gig? By the season finale, the show has reverted her into a wannabe fame monster, albeit with more empathy, as she desperately screams, “We did this together!” when a colleague wins a (solo) journalism award.

The best use of the character comes in “Scam Alert!,” where the newsroom learns about a local catfishing scam and comes to realize that Esmeralda herself has been hoodwinked. Having the most would-be glamorous member of the staff drawn into thinking a photo of Josh Holloway represents her new online boyfriend twists Michael Scott–like behavior into something that feels more keyed into this specific world of small-scale media. For much of the rest of the season, though, Esmeralda doesn’t really fit, as if she’s spun in from another offshoot entirely.

The New Jim & Pam

If ever an office romance were difficult to replicate, it’s the three seasons of quiet yearning followed by many more of low-drama development between Jim Halpert and Pam Beesly on the U.S. Office, itself an adaptation of the Tim-and-Dawn story line on the U.K. version. As a rejection of Ross-and-Rachel-style soap operatics, Jim and Pam were unbeatable; as a model for future “will they or won’t theys,” perhaps less so. The Paper makes its attempt with Gleeson’s Ned, who most closely resembles Jim in his easy rapport with Mare (Chelsea Frei), the only staff member with any real journalism experience. The two quickly bond, and a “will they or won’t they” becomes more of a “should they or shouldn’t they,” because Ned is technically Mare’s boss, even if he mostly treats her like an equal.

Maybe that’s the show trying to mitigate the potential creepiness. In episodes like “Buddy and the Dude” and “Matching Ponchos,” Ned and Mare are paired up like genuine partners, which is also the term he uses to describe her in finale “The Ohio Journalism Awards.” This can be an awkward fit with the somewhat manufactured attempts at conflict, which differentiate the pair from Jim and Pam in sometimes clunky ways. When Mare finds out that Ned has misunderstood her identity as asexual halfway through the season, she’s hurt and disappointed because … he didn’t ask her about it earlier? But surely a military veteran like Mare — whose army backstory ultimately feels like lip service, but whatever — would understand how inappropriate that question would be coming from her manager. It’s a gag that turns into murky characterization halfway through.

That said, it’s interesting to see The Paper grapple with a genuinely thorny issue. Ned and Mare end the season negotiating a first kiss in a scene where Gleeson and Frei tease out a sense of both genuine romance and interpersonal danger. It almost redeems the utter predictability of two similar-age, opposite-gender nice people falling into proximity crushes so quickly.

The New Support Staff

This is the aspect of The Office that really does replicate easily: filling out an open-office plan with a bunch of capable comic actors developing characters slowly without the burden of carrying entire episodes. While there are definitely clear Office parallels in the supporting cast — Nicole (Ramona Young) plays a bit like a more contained Kelly; Adam (Alex Edelman) is the cheerfully dim-witted Kevin of the group; possibly senile veteran reporter Barry (Duane Shepard Sr.) has notes of Creed — Daniels and Koman know how assemble a deep bench, something a lot of Office imitators don’t have the time or patience to build out.

The New Documentary

At first, the presence of the documentary crew in The Paper feels like some throat-clearing to explain the show’s (ultimately somewhat tenuous) connection to The Office and why this show, too, will feature handheld camerawork and straight-to-camera “confessional” moments. But as the season progresses — around the time most mockumentary-style shows start letting the format speak for itself — The Paper stubbornly sticks to its filmmaking, even allowing the unseen filmmakers to occasionally interject with onscreen text when, say, Oscar insists that he hasn’t signed a release that would allow him to be filmed. In “Buddy and the Dude,” a bystander approaches the camera operators and asks them about the filming. In “Matching Ponchos,” the penultimate episode, the cameras are (realistically) denied entry to a compound where Ned and Mare interview the organizers of a possible cult. Oscar, who resists the doc crew early on, brings it full circle in the finale, winning an award and thanking the crew: “I think you guys are the only ones who really see me,” he confesses.

That’s played for comic irony, but in general, the documentary presence isn’t always or even often in the service of gags. The show seems genuinely dedicated to regular reminders that the characters are being filmed within the world of the show, while The Office disappeared into its own world for long stretches, despite the talking heads and signature John Krasinski camera takes (as well as a return to the documentary framework in the final season). This can be read as a clever knock on some of the mockumentary-format comedies that followed The Office, often — ahem, Modern Family — failing to provide any actual reason for the doc-style shooting and talking-head interviews. Moreover, though, the show seems to want to confer a kind of authenticity upon a milieu that many worried would be grotesquely misrepresented by creators who aren’t exactly immersed in local journalism. At the same time, it places some welcome distance between the audience and the characters, keeping the show from getting too sentimental too fast.

Where does this leave The Paper as it finishes up a first season with a second on the way? Through its ten episodes, The Paper works out some of its kinks, as so many freshman sitcoms do. But in this case, that now-familiar process borders on self-consciousness: The Toledo Truth Teller undergoes a stabilization of its own, from barely-there data-harvesting clickbait to award-winning enterprise in what appears to be a matter of a few months. It’s as if the creators believe any institution can undergo a simple freshman-comedy evolution from existential uncertainty to principled triumph, never more evident than when Truth Teller’s season-pivoting story involves them exposing the failure of their parent company’s new product. With its (possibly misplaced) hopefulness about the revitalization of local journalism, The Paper could easily turn into later-period Parks and Rec or Brooklyn Nine-Nine, where the relatability of The Office mushed into a self-regarding cuddliness. It’s a minor relief, at least, that the show is a little less insistent about its characters’ instructive moral correctness, even as it offloads so much of its zaniest bad behavior onto the Esmeralda-Ken duo.

Searching for a logical progression from The Office and like-minded comedies, so far The Paper has come up with a strange, often funny hybrid, with characters experiencing Parks and Rec idealism and Office-style fluorescent-light tedium simultaneously and sometimes incoherently. Years after The Office left the air, we’re still working out just how warm and welcoming it should have been.

Related

- Yesterday’s Fishwrap

- Sabrina Impacciatore Binge-Watched The Office Too

- Peacock Has Already Renewed Its Subscription to The Paper

The sitcom’s freshman season is a strange, often funny hybrid of its direct predecessor and the like-minded workplace comedies that followed.