For the past two years, a group of friends and I have gathered each Wednesday to discuss our progress on a famously grueling book, beginning with Infinite Jest and The Power Broker and continuing with Ulysses and Gotham, a 1,400-page history of New York City that often reads like the world’s most tedious Wikipedia article. The Difficult Book Book Club didn’t start as an explicit strategy to wrest our attention from screens, but that’s what it became: We were nostalgic for school, or rather for a version of school that no longer exists, one where you couldn’t count on ChatGPT to concoct a 500-word essay on postmodernism in a matter of seconds or Zoom into class half-asleep with your camera off. Instead, we discuss the 100 pages we assign ourselves each week, seminar style, returning to book after book in lieu of far more immediately entertaining content (or less depressing, as is the case with our most recent read, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich). “As someone who was once in graduate school and now orders pants for a living, I missed the factor of my life that was educated and well read,” says Laura, who works in film costume departments. “I do think I’m getting dumber,” she adds, and we all nod in agreement. “You forget your brain is a muscle,” says my friend Lars, who works in what remains of the country’s public-health sector. The brain is not, in fact, a muscle, but the point stands.

Twenty years ago, an adult could focus on a screen without interruption for an average of two and a half minutes, says Gloria Mark, a professor of informatics at the University of California, Irvine, and the author of Attention Span: A Groundbreaking Way to Restore Balance, Happiness and Productivity. In 2012, that measure was about 75 seconds, and according to studies done between 2015 and 2021, it then shrank to an average of 47. Half of adults in the U.K. believe their attention span is shrinking, and about that many say that “deep thinking has become a thing of the past.” Multiple best sellers in recent years have attempted to diagnose or cure this problem, from Johann Hari’s Stolen Focus to Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing to Anna Lembke’s Dopamine Nation, while others, including Jean Twenge’s iGen and Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation, blame much of the distractibility and misery of young people on smartphones and social media.

Our inability to pay attention is not just the smartphone’s fault. Computer scientist Cal Newport, who has published several books on distraction and productivity, suspects the problem began with PCs, email, and digital calendars, which allowed bosses more access to knowledge workers’ productivity and in turn increased the number of projects and administrative tasks they were expected to work on concurrently. “If you increase the number of things you’re working on, the proportion of your day that has to be dedicated to the administrative overhead increases,” he says. “You get to a point where this context-switching back and forth from work to email to meetings to Slack is so exhausting on your brain that the only thing you have energy left to do is just the administrative overhead.” He calls this “pseudo-productivity”: You’re not actually doing anything meaningful, but it feels like you are, so you keep going back for more.

Amid growing awareness of the subject, many are trying to reverse the damage. On the platforms most guilty of stealing our focus, people are chronicling their attempts to take back their attention spans sometimes, ironically, in the same clickbait-brained way the sites incentivize. A watercolor artist has a TikTok series called “Attention Span Rehab” on which she slowly paints hypnotizing “zentangle” designs in her notebook while discussing technique, like a Bob Ross for algorithmic video. One duo made an eight-minute YouTube video about how watching the 1975 Chantal Akerman film Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, famous for its long takes and more-than-three-hour run time, helped them achieve deeper focus; the video itself is peppered with sped-up memes and sound effects and is titled, in perfect YouTuber parlance, “This movie CURED my low attention span.” They landed on Jeanne Dielman in part because, as co-creator David A. Torozoff, a 27-year-old actor and writer in London, tells me, he tried reading Dostoevsky and Tolstoy but couldn’t get through them. “As a person living in the modern world, you’re almost set for failure,” he says of literary classics. “The only escape was cinema.” Amy Wang, a content creator known for her study hacks and productivity tips, dared her following of mostly 18-to-24-year-old college students to watch her most popular video — “You’re not dumb: How to FIX your ATTENTION SPAN” — on 1x speed and without scrolling to the comments section while watching. (Many, if said comments section is to be believed, failed.)

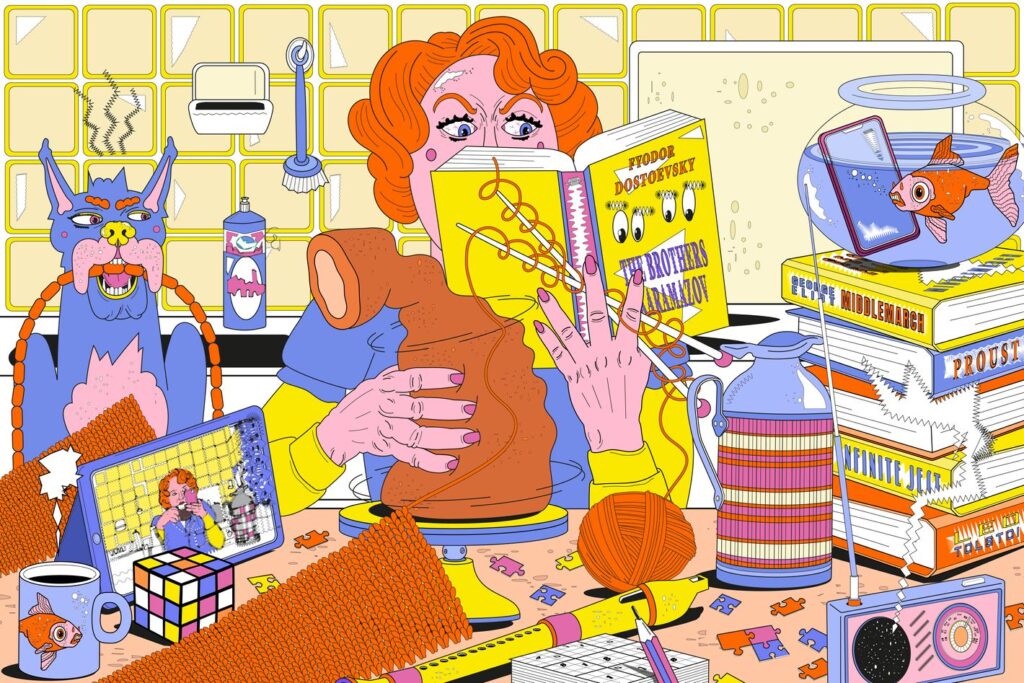

On Instagram, I asked my followers how they were dealing with their own crises of attention or, at the very least, attempting to feel more like human beings. One told me she’s taken up pottery simply because having clay all over her hands prevents her from picking up her phone for a few hours a week, another “rawdogs” his dog walks (as in, the phone gets left at home). People were knitting, crocheting, figure drawing, running long distances, or doing jujitsu just to have something meaningful to do that wasn’t dicking around on the internet. On YouTube, I watched people discover the practice of “digital gardening” — that is, compiling notes on the things they consumed online and building personal wikis to organize them as a way of combating mindless doomscrolling. Sabrina Cruz of the channel Answer in Progress went as far as wearing an EEG a few hours per day for weeks to measure the electrical activity in her brain. “It really came from this concern of like, Am I cooked?” she tells me. The resulting video, titled “how i fixed my attention span,” includes a relatively simple suggestion (meditation), which Cruz still practices about once or twice a week one year later. “When I’m meditating, it feels like a waste of time,” she says. “But it helps. I don’t know how.”

Many of the people I talked to keep their phones on DO NOT DISTURB mode 24/7, use plug-ins like Brick that remove distracting apps, or turn to e-ink tablets for reading and writing without the temptation to open another tab. Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey tweeted in April about how switching to gray scale on his devices was “incredibly focusing.” Whether these small fixes work is a somewhat complicated question. Mark says that in her decades of studying attention, she’s found that for about half the population — the half less able to self-regulate — these blocking programs help in the short term. She suggests that the only real way to sustainably improve one’s ability to pay attention is to develop new habits and exercise willpower, similar to what it takes to quit smoking or lose weight. She says that knowledge workers sitting in front of their computer for long periods of time and hoping inspiration strikes are instead burning themselves out and therefore are more prone to fall back on cheap distractions. “People just don’t take enough breaks,” she says. In one experiment, she had people do work for prolonged periods of time with software blockers, then again without them. When people who are good at self-regulation didn’t have the blockers installed, they would work for a bit, take a short social-media break, and then get back to work. But when they had the blockers, they would work nonstop. “They could have stood up and walked around or chatted with someone. They didn’t. They just kept working straight through.”

One way to prevent the cycle of try-really-hard-to-focus-and-then-keep-failing is to develop what Mark calls a “meta-awareness” of your automatic habits by noting when you’re constantly checking social media or the news. Another way, she says, is to build the kind of life that’s full of replenishing empty space — taking a walk outside, writing poetry, chatting with a colleague, or anything that doesn’t revolve around the pressure to produce.

“Taking more breaks” is a strategy that would seem simple to implement but can often feel just as uncomfortable as resisting the urge to scroll: When I followed the filmmakers’ advice to watch Jeanne Dielman to see if it would, as promised, “CURE my low attention span,” I found it curiously easy to focus on — the film itself is gorgeous to look at, even if the majority of the time Jeanne is scrubbing dishes and making coffee in her claustrophobic apartment for her awful teenage son. The real problem, I realized, was the guilt that came with granting myself the luxury of spending three and a half hours doing something that would not, in any tangible or measurable way, improve my life. My mind drifted to the stovetop grate, which needed cleaning, and my step count, which had yet to hit 10,000 that day. It dawned on me that these concerns have never stopped me from spending the same amount of time on my phone and that the reason for this is my phone prevents me from thinking about anything at all.

In a sea of content about how the attention crisis is making life worse, Daniel Immerwahr, a history professor at Northwestern University, is a rare dissenting voice. The people who claim that there is a crisis of attention — “attentionistas,” he calls them jokingly — often come from legacy media, a field made up of people uniquely prone to becoming distracted by social media, partly because their jobs require long, unsupervised stretches of concentration. “To blame something on an ‘attention crisis’ is to blame it on the public: ‘We’re producing the good stuff; you guys just don’t appreciate it.’ And that’s exactly what every person in a dying medium has said,” he tells me, comparing the phenomenon to the fear felt by Anglican priests in the 18th century who worried that the popular new medium of the day — the novel — was distracting women from prayerful obedience. That the culture is potentially moving away from longform writing and toward audio and visual content isn’t necessarily a sign of intellectual deterioration, he argues: Who’s to say these formats aren’t simply better at transmitting ideas?

“Everyone says that the internet is polarizing our politics and shredding our attention, but actually it can’t be both,” he says. Rather, we’re in an age of “obsessional politics,” where people are factious and often misinformed but not apathetic. They’re watching multi-hour livestreams and plunging down rabbit holes and “doing their own research” — all activities that require massive amounts of sustained attention. And in doing so, they’re finding community.

The solution, at least for myself, has been to find a similar kind of community. At book club, the longer we end up talking (and drinking), the more we start to admit why it’s become such a precious part of our lives. “If I can spend time at book club with a combination of people I love and the connections we make through the story of Adolf Hitler, I’d rather do that. It’s worth ten times any productivity, any distraction, anything else I would have done otherwise,” says my friend Julia, a reporter who has covered the attention economy. Whether or not it has meaningfully improved our ability to focus on a screen for more than 47 seconds on average is almost besides the point because it’s given us an excuse to reframe the hours we spend reading Joyce and Eliot with our phones in DO NOT DISTURB as “productive.” I suspect it’s the same reason bird-watchers mark off the species they see on a given walk or home cooks Instagram their dishes: as a reminder that all the time spent is in service of something greater than the joy they get from doing it, even if the joy of doing it would be enough on its own.

About halfway through Jeanne Dielman, Jeanne goes to a café and sits down with a cup of coffee. It’s the first instance she’s looked even remotely like she’s enjoying herself; the rest of her time is preoccupied with cooking for and cleaning up after men. I found myself almost wanting to clap for her — if only she had more time in the day to devote to these sorts of tiny pleasures, maybe her life wouldn’t look so miserable.

Within a few minutes, however, her small smile fades and she’s staring off into the distance. If Jeanne Dielman lived in the 21st century, this would be the point where she picked up her phone and started scrolling. But I couldn’t look away.

The infinite scroll has ruined our ability to focus. Is wasting more time the key to getting it back?