In the 1970s in New York, everyone slept till noon,” Edmund White wrote in City Boy. Five decades later, very little remains of the bare-knuckle, sexually overripe city that the author recalled in his memoirs and novels, but Ed still slept till noon.

Whenever I sent him an email or a text in the morning, I knew I wouldn’t receive an answer until midday. That delay was hardly an inconvenience: Our missives mainly consisted of swooning descriptions of young men with whom we were briefly infatuated, literary gossip with a dose of self-pity and Schadenfreude, a flowery aperçu by the flaming Henri III of France (that came from Ed), or a vital 11th-hour pep talk to keep writing despite the doubts (also from Ed, who never needed encouragement to keep writing — see his 30 books and hundreds of other published works).

I wasn’t the lone recipient of such exchanges. Ed, who died at home in Chelsea on Tuesday evening at 85, had this kind of lively rapport with many younger gay writers. We all grew up idolizing him for his unsparing, unapologetic depictions of gay life, which managed the vertiginous double art of being both highly literary and deliciously explicit. If you were extremely lucky as a lonely gay teenager, his seminal 1982 novel A Boy’s Own Story fell into your hands and you never looked back. But the magic of Ed had to do with his refusal to stand on the pedestal we all erected for him. He’d rather climb down and be among the boys, joking and putting out cheese plates and listening to the latest in novels and sexual conquests. (You could bewitch him with a particularly salacious hookup story, but you could never shock him.) No question he could be a snob about art, literature, philosophy, and music, but he was utterly democratic where it counts the most: in friendship. He didn’t care about your bona fides. Ed met you as a person — he was a welcoming fellow traveler who had been through it all and understood the struggle.

Can a diagnosis be famous? If so, Ed was famously diagnosed with HIV in 1984, which he took as a no-reprieve death sentence. By then, he had already built a blazing literary-activist career that included writing The Joy of Gay Sex (1977), membership in the gay writer’s group the Violet Quill (alongside the great Andrew Holleran), and co-founding Gay Men’s Health Crisis. Instead of letting the diagnosis slow him, Ed continued writing at a feverish pace. Some of his most poignant essays and novels (The Farewell Symphony, The Married Man) chronicle the devastation and emotional fallout of the AIDS epidemic. Ed himself turned out to be something of a Lazarus.

He liked recounting the time the news anchor Peter Jennings interviewed him in 1989 and asked him what it was like to know he would be dead in a few years. Jennings died in 2005, when Ed was alive and scribbling away on yet another collection of short stories (Chaos) and yet another novel (Hotel de Dream). Nothing seemed capable of killing him. Not AIDS, not negative reviews, not heartbreak (a breakup a few years back with a long-term Italian boyfriend brought him to the brink), not the two strokes a decade ago or the heart attack in 2014 (he collapsed in his office at Princeton; the writer A.M. Homes pounded on his chest until the ambulance arrived). I remember visiting him at the hospital, where he was tucked in bed like a benign teddy bear marveling at the bouquets, and I thought, Surely, he won’t make it out, and just as surely he did. Until last Tuesday, I genuinely believed there was a 50-50 chance Ed would outlive me, 35 years his junior. In reality, the fact that we got him for this long is attributable to his tireless partner, the writer Michael Carroll (charming and brilliant are the first words that come to mind with Ed; the third might be stubborn). It was Michael who kept Ed running. It was Michael who made sure our consummate host was ready to perform by the time we all showed up at seven for dinner.

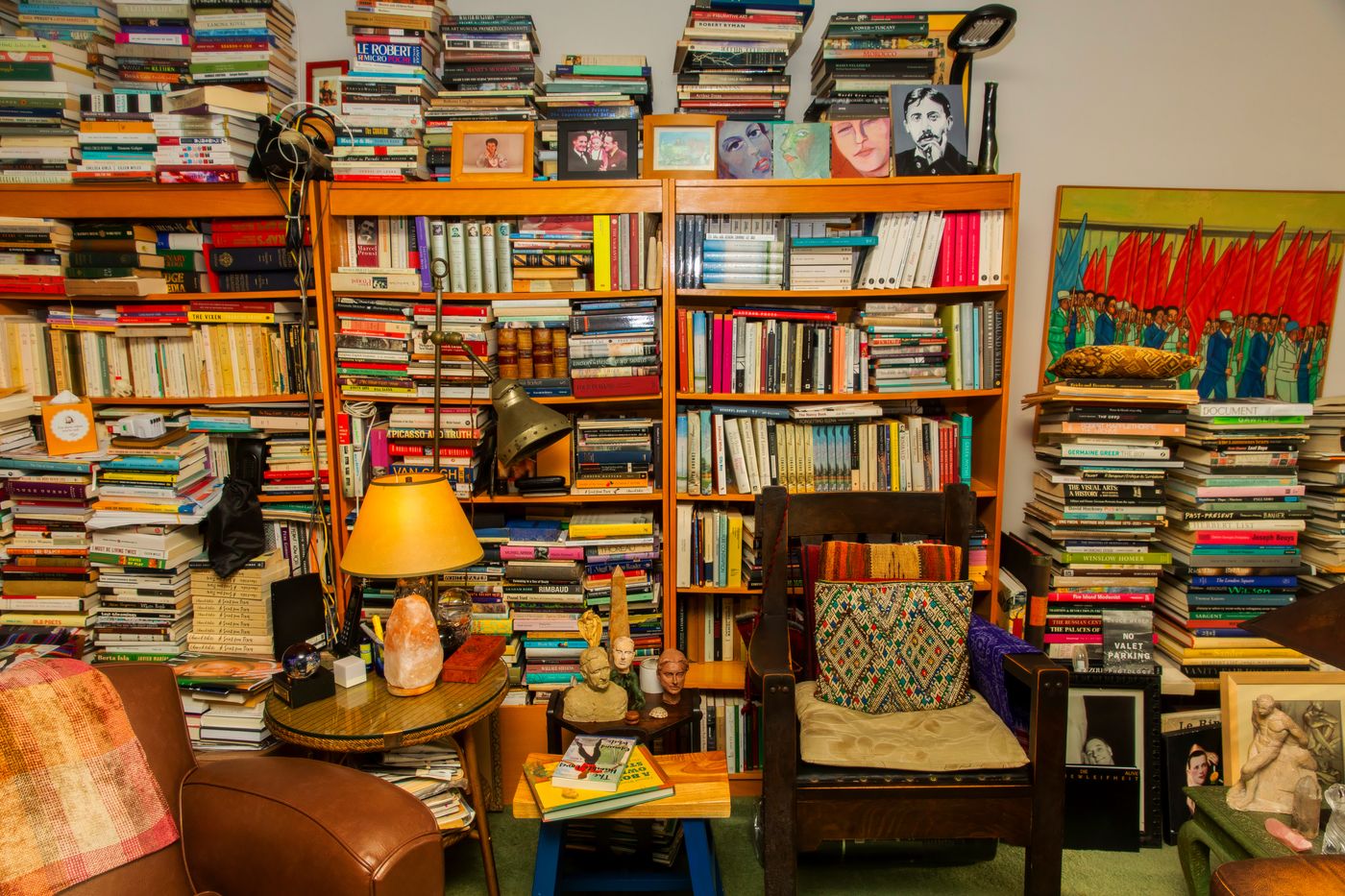

I came late to the Edmund White show. I met him in the early aughts, through a mutual writer-editor friend who shall remain nameless only so I can relay that Ed loved to mention that he had “one of the largest anaconda penises in America.” We were invited to dinner at Ed’s apartment on West 22nd Street, where books engulfed the bookshelves, avalanched over the table, and blocked the fireplace; sometimes it was easier to stand than clear a giant pile off a dining chair. Ed once wrote, “I lived in a world made out of words.”

The apartment was a spacious, yet also cramped, two-bedroom. The carpet was wall-to-wall sage blue. The wooden blinds over the front windows were always lowered. The brown leather sofa hugged you deeply. Pastel drawings of Michael and photographs of Ed (by Mapplethorpe or with Foucault) decorated the walls. Ed didn’t drink (he quit in the 1970s, he once told me, after he realized he was bringing two bottles of wine to dinner parties — one for himself and one for the others), but he encouraged guests to imbibe as needed. He loved to entertain, and in the past few years, as he was increasingly unable to leave home, hosting became his main portal to the outside world that he greedily craved. At that first meeting, we hit it off right away, helped by the fact that we were both born and raised in the same city. Eventually, we developed a little stand-up routine whenever someone asked how we knew each other. Ed: “We both grew up in Cincinnati.” Cut to me: “Ed was two years ahead of me in high school.”

Ed liked to tell stories of picking up Kentucky hustlers at the age of 15 in Cincinnati’s Fountain Square, which was sadly no longer an option for me at 15, terrified of being gay in the city’s post–Charles Keating, “morally cleaned-up” environment of hyperconservatism. From the start, Ed struck me as a romantically worldly figure. He’d lived in Rome and spent more than a decade in Paris. His love affairs and his public disputes were legendary. Every time I risked a mention of a palazzo in Venice or a beach in Brazil, he already knew it, had seduced a man or met a countess or written a travel story for Vogue there. He was the expert on Genet, on Rimbaud, on Proust. Yet even at the very end, even as he told me just two months before he died that he’d started a new novel devoted to Louis XIV’s gay brother, there was a twinkle in his eye of mischievous boyishness, of the wide-eyed midwestern naïf he must have once been. I always attributed that twinkle to his ability to keep churning out such a plethora of plots and to regale with such magnificent stories from his years of decadence and dedication.

And the stories, my God. About Susan Sontag (demanding that he remove the blurb she’d given from his paperback version of A Boy’s Own Story over a perceived slight). Patricia Highsmith (silently skulking around in the background during a dinner party). Gore Vidal (the whole Timothy McVeigh psychodrama, which infuriated Gore and seemed to delight Ed). Truman Capote. Larry Kramer. Tennessee Williams. Ned Rorem. Jilted royals. Actresses, philosophers, politicians. I don’t mean to give the impression that Ed was a fame collector. The majority of his remembrances involved young gay men, much like those who gathered around his armchair or whose beds we’d often just crawled out of — the seekers, strivers, idealists, depressives, failed actors, orphaned lost boys, tragic artists, ambitious grad students doubling as outer-borough rent boys, day-job drudgers with a certain spring in their steps, a blond with a drug problem on the run from his Mormon parents, a hot Colombian playwright who would die on a subway track — an entire unbridled, rowdy community of gay men knitted together in the span of time between July 19, 1962, when Ed first arrived in Manhattan, and 7:25 p.m. on Tuesday, when he took his last breath. That’s what we lost: the symphony of a mind that contained us all.

It’s hard to think of him no longer there, tucked up in Chelsea, watching classical concerts on CUNY TV, reading, or squabbling with Michael. Often, when I’d take a taxi home at night and the car would be speeding up Eighth Avenue, I’d look out the window as we passed 22nd Street to try to see Ed’s building. A few blocks later, I’d look out the other side to catch the lights of the Empire State Building. It never occurred to me till now how much I used those landmarks to orient myself in the city.

When I picture Ed, I think of us cracking up with laughter at his dining-room table. He dedicated his 2016 novel Our Young Man to me, and I, in turn, dedicated my novel A Beautiful Crime to him. He gave me the most wonderfully odd gifts, like a complete set of bedsheets emblazoned with Tutankhamun’s gold mask or a drawing of the Winter Palace Hotel in Luxor that he’d picked up several decades ago. I would send him postcards wherever I went. He’d email a joke about a gorgeous Puerto Rican FedEx deliveryman coming over to scoop him away. No one is young for long enough in New York — except Ed, who managed to stay young and curious until the very end. For many of us, he served not only as a mentor but also as a fellow student, still learning on the job, still falling in love and fighting off despair, still fascinated to know where the day took you. “Being predictable,” Ed wrote in his essay collection My Lives, “is the one unforgivable sin in a friend.”

Books and boys and big dinners at home.