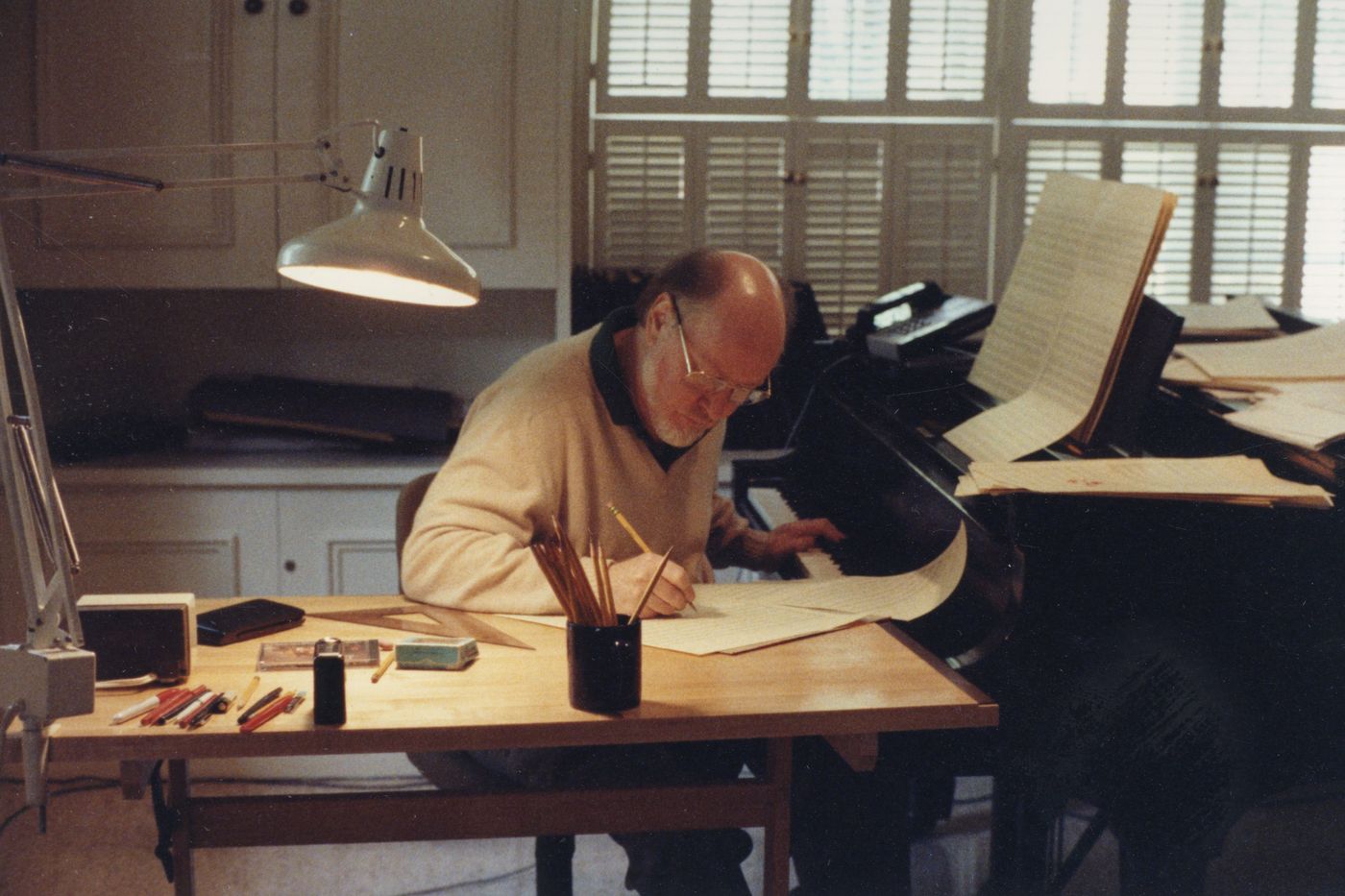

If there’s one thing that supports my belief that John Williams is the greatest film composer of all time, it’s how he brought an almost sacred seriousness to even the lowest-brow movie material. Before Williams, Star Wars was a bunch of actors in Halloween costumes running around wooden spaceship sets. After he waved his conductor’s wand, it was an ornate space opera — a mythic world we are still getting lost inside. Another prime example of his bringing high art to potentially low material is his work scoring Chris Columbus’s Home Alone, which turns 35 this fall.

“For John to be able to connect what I did in that movie,” said Columbus, “not only propels the story forward but from a narrative standpoint it’s like he’s taking the audience’s hand and inviting them inside that world. It becomes immersive. That’s what John’s music does. Certain film scores almost keep the audience at bay, but John manages to immerse the audience in the warmth, or the terror, of the film.”

I fell permanently in love with John Williams’s music when I was 9 and long believed he deserves a serious biography. I hope my new book, John Williams: A Composer’s Life, comes close to giving him the justice his work deserves.

Home Alone was not a project, in any conceivable way, with John Williams’ name on it. Writer John Hughes, moving away from the poppy teenage zeitgeist that made him famous, concocted the story around a simple premise: a young boy is accidentally left home alone at Christmas and has to defend himself against a pair of oily burglars. Hughes tapped Chris Columbus to direct the film on location in the suburbs of Chicago — a local high school was converted into the central, booby-trapped house interior — and he also suggested Macaulay Culkin, an adorable bundle of sassy wit and sweetness, to play the pint-sized hero, Kevin McCallister. Joe Pesci and Daniel Stern were cast as the bumbling but dogged bandits, Harry and Marv, and Catherine O’Hara brought humor and compassion to the part of Kevin’s mother. It was essentially a live-action Road Runner cartoon, which Columbus helped nudge toward pathos by accentuating the arc of an old man next door who forges a surprisingly genuine bond with Kevin.

Bruce Broughton was hired to write the score — early posters and a teaser trailer listed his name in the credits — but when the schedule came into conflict with another project, Disney’s animated film The Rescuers Down Under, he exited. Stranded without a composer in post-production, Columbus was already immediately moving on to his next film, Only the Lonely with John Candy, when he learned that John Williams was interested in seeing a rough cut of Home Alone. John screened the film, and sent word to Columbus that he wanted to score it. “We were just completely overwhelmed,” Columbus said. Here was a small, $18 million movie that he and his producers were simply hoping would double its budget. He had no idea why John wanted anything to do with it — other than, maybe, because Columbus had built a strong temp score that featured Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker, Dave Grusin’s score for Murder by Death, and Mannheim Steamroller’s synthy take on “Carol of the Bells.” “I think he probably saw the potential in that movie that even I didn’t see,” said Columbus, “because I was too close to it.” John was simply enchanted by the movie — and he also saw it as a chance to write some original Christmas carols, in the tradition of his late friend Alfred Burt. “Where else would I get such an opportunity?” said John, who proposed this idea to Columbus. It was also John’s suggestion to have his old friend Mel Torme record a version of “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” for the soundtrack. His enthusiasm for the project was bubbling over — he asked to spot the film twice — and when he got to work on it after Labor Day, he realized his ambitions were probably outsized for this little movie, but “if it moves you, or is something you care about, or something where your spirit resonates a little bit, it’s easier to write music or poetry or anything else. When a composer looks at a film, if it speaks to you, it helps.”

Columbus thought the critical key in John’s contribution was somehow blending the film’s contrasting tones of slapstick, Three Stooges–esque comedy with its warm, Christmassy heart. “John just created this linear glue that held those two tones together,” Columbus said, “which is brilliant.” John hadn’t scored such a straight-up comedy since 1941, and he suddenly remembered how exhausting the genre could be, where every millisecond matters in “these wonderfully burlesque — in the classic use of that word — comedy sequences that the orchestra accompanies so completely in the film, almost like a cartoon where every gesture that the orchestra makes is accompanied by some comedic action on screen.” He coordinated with the film’s sound team and scored each violent vignette — Harry clutching a red-hot doorknob, Marv taking a paint can to the face — right up to the gruesome sound effect, then had the music stand down for the sizzling or thwacking payoff. “If the music had run all the way through, it would have been more cartoonish,” explained music editor Michael Wilhoit.

John had recorded the Nutcracker Suite with the Pops back in 1984, and he liberally borrowed Tchaikovsky’s yuletide sauces for the flavor of Home Alone. Like he did with other classical composers, though, John converted the archetype into a thrilling new form of popcorn energy. The score opens with an homage to “Dance of the Sugar-Plum Fairy,” setting an enchanted, slightly ominous mood with bells and twinkling Christmas lights, and introducing a theme of mischievous mystery. For the sequence where the McCallister family frantically packs in fast-motion, John remixed “Russian Dance” into his own whimsical “Holiday Flight.” The film’s main theme is forecasted right at the beginning, with synth bells ringing the first phrase like church bells calling us into the story. This melody was filled with the feeling of nostalgia and boyhood, with echoes of the old nursery rhyme “Rain Rain Go Away” — and of a glowing hearth with snow falling outside, especially when carried by sleigh bells and other wintry chimes. (Kevin seems to be living inside a Baby Boomer’s ideal of Christmas — watching black-and-white noir movies, listening to golden oldies — which has the interesting side effect of making the film feel timeless.) This main tune became the carol “Somewhere in My Memory,” with words by Leslie Bricusse.

The melody that formed the score’s other carol, “Star of Bethlehem,” is shrouded in religious mystery and it serves the sense of darkness and danger that Kevin is often in. John wrote a perky boy’s adventure theme, usually performed by tuba, which accompanies Kevin’s more carefree moments. For the self-proclaimed “Wet Bandits,” John conceived an eely villain motif worthy of Peter and the Wolf, which stalks and slithers around in the lower end of the wind section. John was a grandfather by now, forever dignified, and as jarring as it is to hear his stately score in a slapstick movie with dialogue like “puke breath,” “cheese face,” and “I wouldn’t let you sleep in my room if you were growing on my ASS” — it oddly makes sense to picture him weaving this fun musical story for his grandchildren, as if gathering them around the fire to read a modern-day Oliver, or A Christmas Carol. His score punctuates the comedy and shivers at the frights; when Culkin dramatically says, “Pack … my suitcase?,” the line gets an exaggerated musical response. When old man Marley makes appearances in the early goings, hovering like the dreaded Ghost of Christmas Future, John manifests Kevin’s terror with the melodramatic “Dies Irae.” This is, unapologetically, story time at the library, where the only thing missing is the sound of kids booing at the villains. But it is also much, much more.

There is a real seriousness to the score — the scheming bad-guy music has the artfulness of Prokofiev, and even the sneaking-around cues have musical integrity and structure. John’s score nimbly dances with the pratfalls and springing traps, never leeching them of their primal, juvenile laughter, but also treating the film’s stuntmen with the same dignity as the Martha Graham ballet company. Something in this conceivably crude, potentially stupid pantomime resonated with him — but he also simply couldn’t help himself but handle it with care, as he did with everything. “A lot of composers can write sweeping, emotional material,” said Columbus, “Very few know how to write comedy cues. I think it’s the most difficult thing in the world. Because you’ve seen so many comedies with a score that just speaks down to the film. I have had nothing but success when John is writing for comedy, because it’s light on its feet in a certain way. It’s not intrusive, and it’s not telling the audience: ‘You need to laugh here.’ It’s just being very playful. The comedy moments in Home Alone — the musical slapstick moments in the film — are just really beautiful in their simplicity.”

The real elevation, though, came in the tender and vulnerable moments that dot the narrative. John’s two carols act as Kevin’s guardian angels throughout his adventure: after Kevin’s first brush with the bad guys, “Star of Bethlehem” sounds with seasonal resolve as he walks outside and declares out loud that he’s not afraid anymore, and it sprints back into the house with him after he’s spooked by Marley. John exploited this theme’s gloomy side for Kevin’s wild overreaction to seeing Marley in the drug store, then kicks it into a sleigh-driven action theme as he runs home. “Bethlehem” becomes even more fraught when Kevin recognizes Harry and hides from the bandits in a nativity scene, and John acknowledged the neighborhood church with a synthesized organ. “Somewhere in My Memory” is the bright sun to the other carol’s melancholy moon, and John spread out a homey, Hallmark card version of it when Kevin finally feels sadness for wishing his family’s disappearance. Likewise, as he walks home one night and sees other families gathering in cheer inside their own homes, the first choral performance of “Memory” is sung Gently with nostalgia. The film pivots when Kevin ducks into a cathedral and overcomes his fear of Marley to have a touching conversation about their respective family woes. A children’s choir is shown singing a series of Christmas hymns in the background — and in the middle of “O Holy Night” and “Carol of the Bells” is “Star of Bethlehem,” as if it were just another classic in the canon of yuletide carols. Truth be told: it qualified. This churchly calm is suddenly interrupted with a rock-like beat on synth drums invading “Carol of the Bells,” which morphs into a steely combat version of “Bethlehem” as Kevin runs home to rig his house with an elaborate series of booby traps (John’s nod to the Mannheim Steamroller temp track).

The film culminates with an escalating parade of pain inflicted on Marv and Harry, and John deftly varied the pace and intensity of his cartooning — with heavy use of pizzicato strings, triangle, and legato bass clarinets — to match the progression. “Memory” flips into action gear when Kevin thinks he’s won and calls the cops (why he waited until now only makes sense in movie logic), and a horn heroically declares the “Bethlehem” tune as he braves a zip line out of a high window and into his treehouse. An accelerated, wobbly development of “Memory” hustles with Kevin across the street, the bad guys follow with their motif, and “Memory” grows increasingly frantic as Kevin goes in through the neighbor‘s flooding basement and runs up the stairs right into Harry and Marv. They talk about paying Kevin back torture for torture, but are suddenly knocked out by Marley — triggering a relieved crescendo of “Somewhere in Memory.” Finally, on an impossibly beautiful white Christmas morning, “Memory” rings gently on bells and the orchestra picks up the melody, singing it with passion as Kevin runs downstairs in faith that his mom came home. The tune turns melancholy when he finds the house still empty and looks longingly outside, but then he hears the front door open and the sound of his mother‘s voice. “Memory” continues delicately as Mom admires Kevin’s tree and decorations, then chimes over undulating, expectant strings when Kevin meets her with a frown — which he immediately replaces with a huge smile, and the orchestra wells up joyously as mother and son hug each other tightly. The film ends with a delicate bell ostinato introducing one last reprise of “Memory,” played on a synth harpsichord, which is joined by the whole orchestra as Kevin looks out his window and sees Marley hugging his granddaughter, tears in his eyes as he waves to Kevin. For all of its physical comedy and Christmas wish fulfillment, the real reason multiple generations developed a powerful bond to Home Alone is because of these tearful moments — and because of John’s sparkling, heartstring music.

From John Williams: A Composer’s Life by Tim Greiving. Copyright © 2025 by Tim Greiving and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

The Star Wars composer’s last-minute score gave gravitas to the now-classic comedy.