Simulating sex on camera is one thing. Letting the audience in on the experience is another. Penn Badgley has caught heat (and 100 headlines!) once before for speaking about intimacy onscreen, so you might expect him to steer clear of the subject. Instead, he leans in. This time, Penn offers an unflinching account of an experience most actors will simply call “technical.”

His is a story that begins long before the You memes and thirsty edits on TikTok, with a little kid in Washington, trying to cry on cue. In his essay “In Camera,” Penn reverse-engineers how that kid became the adult staring his scariest scene partner directly down the barrel of the lens. Penn’s relationship to the lens — and the curious eyes watching through it — is a prism into the off-screen forces that shaped his early life.

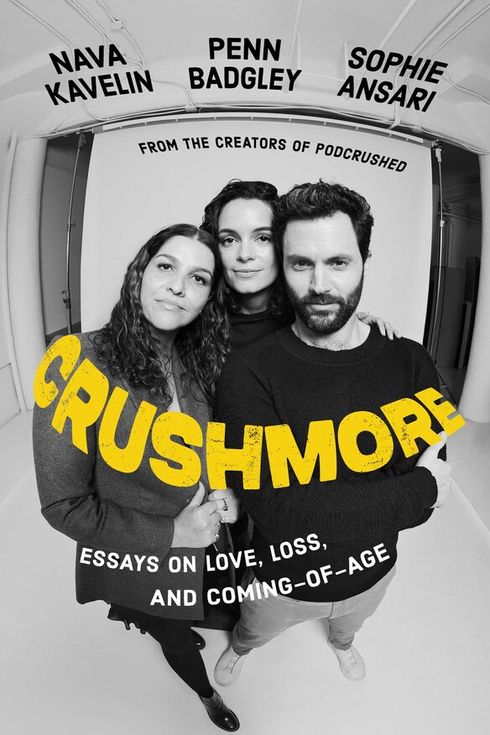

Our new essay collection, Crushmore, widens the aperture to explore the moments that make a life, particularly one that is coming of age: the euphoria of a first love and the sting of rejection; the gut punch of an untimely death and the sometimes gentle, sometimes turbulent ways faith heals wounds; the warped funhouse mirror of body image and the treacherous-yet-seductive pull of fame.

The result is a mash-up of celebrity memoir and universal coming-of-age diary — a collection that’s funny, heartbreaking, and bracingly self-aware. Penn is joined by us, his Podcrushed co-hosts and occasional “friends,” Nava Kavelin and Sophie Ansari. Penn likes to pretend he doesn’t even know who we are, but the joke is on him because nothing cements a friendship like binding it in between hardcovers.

Fame has an enormous impact on an actor’s life, on my life, which I’m often unable to ignore anywhere but two places — within the walls of my own home, and in front of the camera. In both places, quite fortuitously, the essence of my role is the same: to be supremely present, and to try at every turn to open myself up, rather than perform what I think would be right, or what I’ve seen before. This can be difficult in either space, but it is in front of the camera — only in front of the camera, nowhere else — where the seed of fame is generated. The camera is, therefore, the polar opposite of a true home. I have to remember that always: it wears a mask, even while my job is to try to remove my own.

Mid-pandemic, early 2021: I’m filming the third season of my very popular, very beloved, very, very great Netflix series You, in which there are quite a few intimacy scenes, as we call them in the biz — simulated sex, or anything sexual like, say, masturbation (my show has plenty of both, for reference). We’re shooting a fantasy sequence and as a stylistic choice, one that makes a lot of sense, the director has chosen to place the camera directly in front of my face. My character is meant to be humpin’ on his wife, with whom he has become not only bored but also contemptuous, so he is imagining he’s having sex with a librarian he’s been flirting with, and whom he will later attempt to kill (if you haven’t seen the show, believe it or not, that actually isn’t a spoiler because he does this every single time, and if you haven’t recognized that by the third season, I’m sorry for your loss).

What this means for me, practically speaking, is that the director wants a close-up of my face as my character Joe is deep in dissociative reverie mid-coitus. The camera, a very large apparatus weighing just about seven hundred pounds — lovely coincidence — does not allow space for itself and my scene partner (Victoria Pedretti, who brilliantly played Love in seasons 3 and 4 of You, and who is more beloved than I am by many fans of the show). If anyone or anything has to go, it won’t be the camera; it will be my scene partner who sits this one out. This means that rather than simulating sex with her and looking at her while the camera watches us together, I’m going to have to simulate sex by myself, effectively humpin’ on the air, on a fake bed in a fake room, surrounded by a film crew. Oh, and I’ll be in the same nude thong I’ve been wearing all morning as we complete the scene, of course.

Because this is not my first rodeo, I’ve realized all of this before the director explains anything to me. I can see that it’s what the shot requires, and it’s a good shot. That’s fine and clear. So, the director — a thoughtful and talented woman named Silver Tree — approaches me before she says anything to the camera department about what the shot will need. I appreciate her deference to me here. I’m in a robe (nude thong on underneath) and flip-flops. Like everyone else in a sound stage, Silver is fully dressed in sweater, jeans, and boots with an N95 mask on. Whereas one can see nearly all of me when I disrobe for the scene, all I can see of Silver is her eyes — but that’s all I need. I can detect a sweetly nervous smile underneath her mask, and just a hint of (utterly professional) mischief. I know what she wants, and she knows I know, and she knows that I already agree it’s what the scene needs. So, she shuffles up to me, almost doing a two-step, as she says, “Penn —”

I cut her off, gently. “You’re putting the camera in my face.”

She nods. “Yep.”

“Victoria can’t be there.”

“Nope,” she says, and clasps her hands behind her back diplomatically.

I chuckle, adjusting the waistband of my robe. “So, I’m going to be …”

She chuckles, too. “Mm-hmm …” It is her ellipsis which hangs in the air that surprises me, though. I pause. Silver’s eyes shine, and I realize —

“You want me to look in camera, don’t you?”

Silver’s slow and silent nod is at once confident, demure, sheep- ish, and respectful. It will be one of my fondest memories of her when the series is long finished. We both laugh heartily now. Not only will I be humping the air with the camera in my face, but I’m going to be looking straight down the barrel of the lens, something I reflexively never do. You never let a mean girl know you’re look- ing. Looking in camera ruins a take. Looking in camera is crossing a great metaphysical threshold because you’ve acknowledged the audience. The spell so delicately, exhaustively, extravagantly cast is broken with only a glance — unless, in rare circumstances, it works. This is one of those rare circumstances, made rarer by the fact that I will be simulating sex with the camera and, by proxy, the audience. For me, it would be truly naive to not consider now, even briefly, that — like so many other moments captured of me performing on this show — this one may very well become a meme.

I have a few minutes while they set up, and I don’t think about it much. Not the point of the scene or the possibility of my body, a spectacle, living in a corner of the internet, infinitely humpin’ on a GIF that sixteen-year-olds can use in a group chat. Now comes a young production assistant, totally overworked, underpaid, ambitious, stressed-out, masked up, her cargo pockets bulging with water bottles and script pages (should I ever need either one), a coiled plastic earpiece crammed into her ear canal connected to the walkie-talkie that is clipped to her utility belt and crackling incessantly with the urgent demands of any and every one her senior in any department — which is literally everyone on a film set — and so calmly, so kindly, this production assistant says to me, as she has hundreds or thousands of times this season:

“Camera is ready.”

“Thank you, Jessica.”

I have another thirty seconds to not really think about the scene, or any of the broader implications of what my work entails, as I walk from my Gore-Tex foldup camping chair in a dark corner of the soundstage to the bedroom set. The set is meant to look like a beautiful home, and it does. The entire crew has been working to make sure that it is beautiful, and to help the audience forget it’s not real. Here, the camera and sound crew make final adjustments to their highly specialized machinery that will capture my performance. I nod at Victoria as she sits on a little wooden apple box to the side of the bed, wearing her own robe and flip-flops that match mine, an N95 mask on. Her eyes give me an encouraging smile (she’ll have to do this, too, in the next camera setup).

Two women, both wearing full parkas and beanies, masks on, come to glance at my face and hair. I’ve not been wearing a mask while we film my side of the scene because it would leave telling marks on my face that the camera would see, and which would break the spell for the audience. The camera won’t allow it.

“I look great, let’s be honest.” We laugh, and they scurry away as I begin to untie my robe and step out of my flip-flops. A wardrobe assistant approaches in her fleece hoodie and hiking boots, and we nod at each other as she whisks away said robe and flip-flops. On a stage of at least one hundred people dressed like they are going camping on a cold October day, all in medical-grade masks during a global pandemic, some of whose faces I will never see, I am now as nude as I was born but for a flimsy thong, and this is my work. I’ve made it, I tell myself. Little Penn would be awed and humbled.

I kneel onto the thin, false mattress where the camera rig — a large and unwieldy apparatus — hovers on a jib arm that extends from a Transformer-esque machine, one that is modified from the original Moviola Crab Dolly that used to load bombs into planes during World War II. The whole setup looks like a giant creature with an extremely dense and compact body, a long, protruding neck, and an almost-cute face — a little bit like Wall-E, and a little bit like the servant-pet-robot from Red Planet that turns on Val Kilmer and tries to murder him. This is my pretend lover for the next ten to fifteen minutes.

The crew has quieted respectfully, as they always do, and there is an impossible silence inside a twenty-thousand-square-foot space crowded with people and electronic equipment. On the bed, I shuffle on my knees toward the camera, my lover forged from metal and glass hovering just above a down pillow with a four-hundred-fifty- thread-count pillowcase. As I approach, I get onto all fours, scooching myself closer so that the camera is beneath me and looking right up at me. I’ve not yet turned my face to peer into its eye. There are the strangest of butterflies flitting in my stomach. I realize as I try to look into the lens that, for a moment, I can’t. I simply cannot. It’s too bald, too bold, too bawdy; and I feel naked because I am almost naked. I really can’t take this seriously. I start to giggle, and then I laugh, quaking on all fours. Every part of me that can jiggle is now jiggling. Our camera operator starts to laugh, and so does the sound guy holding a boom mic just above my head. We all laugh, and it’s a relaxing, unifying moment. But we must quiet, and eventually we do. I finally look into the lens. You (my show, not my reader) uses these beautiful, old anamorphic lenses from classic film cameras — somewhat rare these days. The thick, meticulously distorted glass in the barrel captures and reflects light in subtle and enchanting lines like an artistic rendering of a black hole in space. The depth of blackness inside the lens is unnatural — in fact, it is pitch-black surrounding the very center, where a perfectly round dot glows with the faintest red light, like a thin membrane, a veil between me and the other side (and the audience). The lens is such a sensitive and powerful mechanism that it usually needs to be encased by a dulled metal frame with little flippered visors on it. This is called a matte box. It fits over the lens like a picture frame so the visors can flip out to shield the lens from any light that would hit it directly and create ghostly shapes in camera.

Beholding the matte box, I notice that as it casts the lens in shadow, all the dimension I could see before in the lens is now gone. I realize this little black box has momentarily hidden from me the true nature and intensity of the seven-hundred-pound apparatus of blown and curved glass, brushed metal, and intricate circuitry, here to record everything I do. It appears the eye is closed; the mirror is shrouded. This is not typically its purpose, but today the little black box has made me just a bit more comfortable as a I continue my life’s work.

The time has come for me to hump.

“Action.” Silver’s delivery is, possibly, more delicate than mine will be.

I’m not home, but I can imagine that I am. There is no one in front of me, but I can imagine someone is. A moment ago there was only resistance in my body to do what was needed, but upon the utterance of one word — action — I am supremely present in the face of sheer absurdity. I look in camera. And I hump my ass off.

Excerpted From the book Crushmore: Essays on Love, Loss, and Coming-of-Age. Copyright 2025 by Sophie Ansari, Penn Badgley, and Nava Kavelin. Published in the United States by Gallery Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Crushmore: Essay on Love, Loss and Coming-of-Age

Penn Badgley on the art of filming a sex scene for You.