When the world drops out from under us, we turn to intangible sources of certainty: God, if you believe, or the universe, or tarot cards, or some high-vibrational being who can divine a murky future. For Lizzo, that’s Wendy, a psychic medium who works out of a squat lavender-painted building in the Valley. Lizzo started getting regular readings from her five years ago, just as her career exploded. There’s no negativity in Wendy’s sessions, Lizzo explains as we make our way through the sage-scented, labyrinthine hallways of Pure Heart Collective psychic salon, pausing so two “angel assistants” can show off the Sailor Moon knee socks they’re wearing in her honor. “It’s all love and light,” she says.

Today, on a perfect late-April afternoon in the backyard of Wendy’s salon, it really is all love and light. The sun streams so fiercely on Lizzo’s face that beads of sweat collect on her upper lip. Wendy, an ageless blue-eyed platinum-blonde “baddie angel,” as Lizzo calls her, flits around the salon’s backyard café plying us with herbal tea and compliments.

“Sweetie! You look gorgeous,” she exclaims, appreciating Lizzo’s glowing skin and the way her copper-colored Afro frames her like a halo. Then, upon taking in Lizzo’s Valentino kitten heels and pristine white Capri pants: “You look rich!”

“You look so good, Wendy. Stop it! This fit, honey!” she says, gesturing to Wendy’s cream tweed skirt suit. “Is that Chanel?”

Cost-prohibitive for a psychic medium. “I wish,” Wendy says, her laugh tinkling in harmony with her many silver bracelets. As she moves around the bar to make us tea, Lizzo fills Wendy in on her past few days. Over the weekend, she celebrated her 37th birthday at an intimate dinner with her close friends, her mother, her sister, and a Sailor Moon cake. She attended a meditation gathering at Jay Shetty’s house (she was a guest on his motivational podcast, On Purpose, earlier in the month). She drank mocktails alongside Gabrielle Union and met one of Shetty’s “monk teachers” — a “smooth” older man who identified Lizzo as “so kind,” she gushes.

Teas brewed, we settle into Wendy’s womb of a reading room. Half a dozen scented candles burn on a crystal-strewn altar, a contrasting tableau to the desktop computer and printer in the corner (spirituality is a business, too). Lizzo plops down in a straw chair with familiarity, arranging the many pillows around her and assuming a palms-up position. Wendy sits across from her and begins to stroke Lizzo’s palms with the tips of her aqua-and-pink acrylic nails. They sync their breathing at Wendy’s lead: “Inhale. Exhale. Inhale. Exhale. Last Inhale. Release and say ah.” Lizzo ahhhhs; she shakes her body out. She focuses on Wendy’s third eye. Wendy slips into a trance state and begins to channel Lizzo.

“I feel like this birthday … very important … with almost like a new version of me being born. Me being formless, being you,” Wendy-as-Lizzo says. “You’re also stepping into the world with a lot more confidence. A lot of things. And also there’s some new things going on with producing, like producing projects. And it could be a film, too.”

Each new psychic prediction elicits a whoa and an emphatic nod from Lizzo: being onstage, a world tour, more time in New York, and possibly living in Japan. Her throat chakra, which previously had been blocked, would soon open. And what’s this? Real estate? Lizzo’s eyes widen, and she throws a quick glance over at me. Wendy had stumbled onto territory that Lizzo immediately deemed off the record. Watching people with their psychic is more intimate than watching people have sex. An uncomfortable silence follows as Wendy channels something that can be on the record.

Lizzo and I first met in 2019, when I profiled her for this magazine just as she was about to break out. She was open. Candid. Boundaryless. She invited me out with her clique of friend-ployees for a late-night postshow dinner that turned into a raucous party. We drank tequila. We cackled over dirty jokes and orgasmic chicken wings. Fame — the real fame she has since achieved — was still just a theory, an A&R rep’s whispered gut feeling about star potential. She hadn’t yet released her debut major-label album, Cuz I Love You, but she had announced herself to the public in no uncertain terms: thick, confident, with a brand so strong, so body positive, so sex positive, so pro-Black, and so feminist that her rise to fame seemed to signify a change in culture. She was, as she announced in one of her biggest singles, “100% That Bitch.” (She later trademarked the phrase.)

People liked the music — omnigenre, toe-tapping earworms that were raunchy but not so raunchy they couldn’t be used in Target commercials — but they liked Lizzo more. They liked that they’d never seen anything like her, that she defied their expectations just by being herself: a classically trained flutist who loved anime, twerked on anything, and was candid about her mental-health challenges, her love of sex, her love of her own ass cheeks. She used her whole self (her body, her joy, her provocative outfits, her emotional vulnerability) as a tool to change people’s minds about who got to be a mainstream pop star — or really just who got to be. Being Lizzo was an act of resistance; liking Lizzo, then, felt like taking part in a revolution. To be part of a society that made Lizzo one of the biggest recording stars of the early 2020s was a small indicator that progressive values and virtues had survived the (first) Trump presidency. To like Lizzo, to love Lizzo, to put Lizzo on your pre–Soccer Championship Pump Up playlist, to attend a Lizzo concert, to walk out to Lizzo at your election rally was to be demonstrably on the right side of history. If it sounds hyperbolic now, it wasn’t then.

But high perches are precarious. In 2023, news broke that three of her former backup dancers had filed a lawsuit against her, her touring company, and her dance captain for sexual harassment and a hostile work environment. Suddenly, Lizzo, an artist who had spent her entire career empowering others, combating racism and fatphobia, was accused of cultivating an environment where those things thrived. It wasn’t just a lawsuit; it was a wrecking ball to every inch of the pedestal she had been placed on.

Lizzo hadn’t put out new music since before the lawsuit. This year, she has begun tiptoeing her way into a comeback. In February, she took to Instagram in a Tina Turner–esque outfit — bodysuit, sheer tights, heels, little leather jacket — and power-posed in her lush yard. She stood in front of a giant poster of her most recent album, 2022’s Special, and scrawled BYE BITCH in red spray paint across an old version of herself. “End of an era,” she wrote as a caption. She was coming back with a different sound: more ’80s rock, less disco-R&B-funk. The album, titled Love in Real Life, was due out in the summer. She released two singles, then launched a three-stop mini-tour. She went on Saturday Night Live, performing the new songs while wearing a T-shirt with the phrase BLACK WOMEN WERE RIGHT and another with the word TARRIFIED emblazoned across the chest, grabbing at the sort of politicized gesture that would typically make a headline or two.

Except this time, nothing was sticking — hence this well-timed visit to the psychic church of Wendy. Earlier that week, Lizzo had gone to a meeting with the higher-ups at her label, Atlantic Records, to discuss a restart on the album process. The first two singles hadn’t performed as well as she — or the label — had expected. Wendy senses Lizzo’s wavering confidence. There was a chance that, even if she made the same music she always had, an audience might not want to hear it. She was coming back to music after a public controversy to a world that had changed, and, even more destabilizing, she had changed too. Who was Lizzo supposed to be now? Wendy homes in more. “It’s almost like you doubt your own ability, so you thought somebody else had to tell you how to be cool,” she says. “You’re not going to do that anymore.”

She envisions Lizzo filming a new video: “God, it’s so good. Everyone’s freaking out on the internet. We’re freaking out. Got to watch this video. Got to watch this video. It’s so good, honey. It’s going to be amazing. It’s got a ton of energy going into it. What are you wearing? Are you doing something with your hair?” (Yes, Lizzo would be doing something with her hair.) She predicts Lizzo will have a new song, fun and sassy, that will be huge. She starts singing the energy of it — not the tune, just the vibe. “I know who I am,” she chants in a sort of Sprechgesang-rap cadence. The message of the song that will work, Wendy says, isn’t bitchy. It’s like, “I am powerful and I love myself and I accept myself.” Lizzo nods emphatically in response. Wendy beams. “I think it’s such a good song. I feel like people are going to be singing it everywhere,” she promises.

After the reading, Lizzo is energized, activated, and hungry for post-divination fro-yo — “Girl’s day,” she singsongs while leading us to a quaint shop at the end of the block. She contemplates everything Wendy tapped into during their session. “I put out those two singles, and it feels like I had a crash course in what putting music out as a pop artist in 2025 looks like, and it’s … interesting,” Lizzo says. “The industry and the landscape change every year. What worked last year is not going to work this year.” With Special, she says, she understood the playbook and the pacing. She knew all the “gatekeepers from radio to marketing to media,” and she had an understanding of how to build buzz for a hit. But it wasn’t just the industry she’d understood. She’d understood something about the Zeitgeist and how to reflect it — define it, even. She had benefited from how things were. But now, maybe, she didn’t understand. “I am flying by the seat of my pants,” she says, “which is crazy because I had three years to plan this shit out, and all of my plans kind of crumbled.”

After fro-yo, we head back to Lizzo’s house, entering by way of her cluttered garage, moving through racks of evening gowns and feathered coats in garment bags. I trail behind her as she sweeps into the spacious living room decorated with a burgeoning collection of works exclusively by Black artists. She gives her personal chef, K.C., a big friendly hello as he finishes preparing lunch, before leading me out to the terrace where we’ll be eating. Lizzo has been documenting her recent weight loss, including how her diet has changed (no longer vegan, she, like the rest of society these days, is focused on protein). How long has K.C. been part of the routine? I ask. Lizzo pauses before declining to answer.

The rollout machine is in full motion. She’s parsing the details of her life, determining which part of the past couple of years she has promised to each outlet. Details about her new diet-and-fitness regimen are reserved for Women’s Health, where she’ll reveal how “radiating back pain” contributed to her lifestyle changes and evolving relationship to body positivity. In the past few years, Lizzo has been talking about her shift to body neutrality, which she defines as “when somebody walks by and their body doesn’t look like yours and it doesn’t even blip your radar.” But, she adds, “I don’t feel like people clocked my use of body neutrality as hard as I wanted them to.” When she changed her messaging — and even more so when she began to lose weight — some fans felt she was abandoning what she had previously championed. At the same time, the larger body-positivity movement had grown more commercialized. Was her shift away from body positivity a betrayal of her values, an attempt to keep up with the times, or just her own personal evolution? The culture moved on soon enough: Everyone was on Ozempic now. She knows people assume she is too — it doesn’t help that a comment she made on a recent podcast seemed to be an admission of usage. (Her response was misunderstood, she says, and if you listen closely, she did not admit anything.) She has been showing her work, posting exercise videos, and discussing her dietary changes. She believes she can “help create a new language”: It was not “weight loss” but a “lifestyle change that resulted in the intentional release of weight,” she says, with careful consideration hanging on every syllable.

On the patio as we settle in for lunch, Lizzo is finally ready to relax. She unbuttons the top of her white Capri pants before she sits down and asks Dosh, her assistant, to bring her the “black Yitty cargo pants.” The garment is delivered; she strips down and pulls them on, commenting to no one in particular that now she is wearing a full Yitty ensemble, as if she’s doing spon-con for the size-inclusive shapewear brand she launched in 2022. Her whole house has an “unbutton your top button after a long day” energy: an easy-access cold-plunge pool, a room dedicated to her impressive crystal and Baby Yoda collections. Sound bowls dot the yard, ready to soothe the nervous system at a moment’s notice.

Lizzo moved into this house (on a lot previously owned by her friend Harry Styles) in the spring of 2022, when there was no better time to be Lizzo. By then, Melissa Viviane Jefferson, a Houston-bred, flute-playing band geek who had intermittently lived in her car and crashed on couches while trying to make it, was seeing the fruits of her labor. Her reality show, Lizzo’s Watch Out for the Big Grrrls, in which she gave plus-size dancers a chance to tour with her, won an Emmy. A documentary about her life, Love, Lizzo, premiered on HBO Max. She dropped a single, “About Damn Time,” a signature flute-heavy, post-pandemic call to arms for people to get out of their homes and enjoy life again, which would go on to win Record of the Year, marking the first time a Black woman had won since Whitney Houston for “I Will Always Love You” in 1994. The Grammy catapulted her into a new stratum as an artist. She was vibrating at such an elevated Lizzo frequency that the Universe rewarded her with a personal life, too. In 2022, she also began a serious relationship with comedian and musician Myke Wright.

By the end of her world tour for Special — 79 shows that took her from Sunrise, Florida, to Niigata, Japan — Lizzo was on a high so high she never could have seen the crash coming. She got offstage that last night in Niigata, ready for some downtime before getting back into the studio. In the following days, three of her former backup dancers, Crystal Williams, Arianna Davis, and Noelle Rodriguez, filed a lawsuit against her, her former dance captain, and her touring company. Out of all the allegations, a few anecdotes have defined the controversy. The dancers allege they felt pressured to go to strip clubs while on tour, including one night out at Crazy Horse, a well-known Paris burlesque club, where they say they weren’t aware the performers would be nude. Another night at Bananenbar, a club in Amsterdam, they say Lizzo “cheered loudly to motivate” them to eat a banana protruding from a performer’s vagina. There was a 12-hour rehearsal day, during which one plaintiff says she was too afraid to leave the stage to use the bathroom.

From her post-tour vacation, a blindsided Lizzo sprang into action, she recounts. She had to talk to her lawyers. She had to talk to her manager. She had to write a statement. “It was hard. My best friend was there, and her kids came. I was trying to be happy, but we’d be at Hello Kitty! land, and I’m in the car crying out of frustration that I could not say what I wanted to say and just get on Instagram Live and be like, “What’s going on?” She couldn’t speak directly to her fan base or her detractors: “It was legal. Everything you say and do will be held against you in the court of law.”

This was different from other times she’d experienced backlash. More so than other celebrities, Lizzo had mastered the art of responding and repairing. When she was called out for using ableist language in her song “Grrrls,” she apologized, rerecorded the offending lyrics, and was forgiven. But now she had to issue an official statement, which she did on Instagram later that day: “My work ethic, morals, and respectfulness have been questioned. My character has been criticized. Usually, I choose not to respond to false allegations, but these are as unbelievable as they sound and too outrageous to not be addressed.” Lizzo vehemently denied the allegations, which she said were false or half-truths at best.

She continued on to Kyoto with her boyfriend. She stayed off her phone as much as she could. She meditated. She sat in steamy onsens. They visited a forest where she sat among buzzing cicadas and tried to find stillness. “The cicadas are loud as shit,” she recalls. “The whole time, they’re just like Eeeeee, eeeee, eeeeee.” It had the same effect as a sound bowl. She sat down on “this old rock-something thing” by an old tree and said to herself, “This tree was here before the lawsuit, before the internet, before the phone, before me. And this tree’s going to be here after me, after phones, after the backlash goes away. This is the only thing that’s real.” It gave her a little sense of peace, she recalls. “The peace that everything comes to an end.”

Embodying the age-old internet adage “Touch grass” got her through those first days. But then she had to go back to L.A., where the fallout was public and escalating swiftly. Upon landing, she was hit by the total weight of her situation. She had her first full-blown panic attack.

Williams, Davis, and Rodriguez appeared on Entertainment Tonight to voice disappointment with Lizzo’s statement. A few former collaborators spoke out in support of the dancers, citing their own negative experiences working with Lizzo; a documentarian revealed she had dropped out of a project with Lizzo in 2019 because she “was treated with such disrespect.” Op-eds and think pieces questioned how her empire of positivity could harbor such toxicity. People came to her defense. Eighteen staffers, including a number of dancers, signed declarations disputing many of the claims made against her.

A few weeks later, hours before she was set to receive the Quincy Jones Humanitarian Award at the Black Music Action Gala, a second lawsuit hit. A former wardrobe assistant for her dancers, Asha Daniels, alleged that Lizzo’s 2023 tour was an environment where she was subjected to “racist” and “fatphobic” comments and sexual harassment. At the gala that night, Lizzo went onstage and made a tearful speech, promising that despite her current situation, she was going to “continue to put on and represent and create safe spaces for Black fat women, because that’s what the fuck I do. It is my purpose, and it is an honor.”

The allegation that almost undid her wasn’t sexual harassment or accusations of a hostile work environment. It was that anyone would believe she had fat-shamed someone, that anyone would think everything she had been living and embodying was performative and for profit: “How can any of that be performative and fake when it was my actual life? Who can keep that façade up for years? For people to say it’s beneficial to be body-positive when that wasn’t even the trend. I made it the trend. I’m one of the ones who forged it.”

She surgically defends herself, pointing to the lawsuit itself like her own legal counsel. The accusations did not include explicit comments pertaining to weight; rather, the suit alleges Lizzo asked Davis a series of questions about her “commitment to the tour” in April 2023 that gave her “the impression that she needed to explain her weight gain and disclose intimate personal details about her life in order to keep her job.” Davis believed this because, she claims, “Lizzo had previously called attention to” her weight gain “after noticing it at the South by Southwest music festival.” Lizzo calls out the lawsuit’s vague language: “I would get it if it said, ‘Then [Lizzo] said “You fat bitch,” and then she pushed me, and then she grabbed my stomach.’ But it doesn’t even say I did anything, and y’all believed nothing,” she says, working herself up. “Y’all believed a headline. It was like, Holy shit, this person, me, the real me, that I’ve put on display so proudly and fearlessly for so many years, isn’t me anymore to the world.” She had always been “very fun,” “very flirty,” “a little hypersexual, a little boy crazy.” She had always presented herself authentically, but now the world was upset with that presentation. “That’s like somebody taking who you are and rearranging it into something you’re not. They turn you into a fish, and you’re like, But I’m a human. I’m not a fish. How am I going to live life as a fish? I live on air.”

I ask Lizzo how this could have happened. How did a human turn into a fish? She tells me how: She hadn’t realized how famous she had gotten, so she hadn’t adjusted her way of working. Lizzo had always been proud that she worked with people she considered close friends or who became close friends through working together. When she was an indie artist, she traveled in a van with bandmates. The people who did her hair, executed her choreo, did her sound were the people she partied with, gossiped with, confided in. Boundaries were permeable. But then her fame grew rapidly, and she wasn’t prepared. Her Amazon show and tour were her first times dealing with such a large staff, many of whom she didn’t know personally. “I had this scrappy indie-artist brain,” she says, “but I was a Grammy Award–winning, Emmy Award–winning artist. You can’t move in the same way.”

In the weeks and months that followed, she started losing friends in “emotionally violent ways,” she says. She pushed people away. “All I had was my therapist, but then I was too depressed to even want to talk to my fucking therapist.” Amid all this, her 18-year-old Champagne Maltese, Pooka, died on Christmas Eve. “I’ve had periods in my life where I’ve been suicidal,” she tells me. Her father died in 2009. “This, I would say, was a parallel to that time. I was staring at the ceiling and feeling a stillness come over me and being like, If I died right now, it would be fine.” While driving, she would have moments when she’d think she wouldn’t care if her car veered off the road. She contemplated poisoning herself. “I’m not trying to be like, Woe is me, because I did it in a really big nice house,” she cracks, trying to steer the conversation back to something safer, but then she breaks off. In March 2024, she posted “I quit” on Instagram saying she was overwhelmed by online attacks. Days later, she clarified she wasn’t quitting music but rather a cycle of negativity. She laughs at herself as she recounts muddling through her emotional responses, which she sums up as “thinking I was ready to be back in the world and not being ready to be back in the world.”

“It was so weird to watch everybody attack her because it actually had nothing to do with what was going on,” the musician SZA tells me. She and Lizzo met around 2014 and have become travel buddies, spiritual sisters, and creative collaborators. The way they talk about and to each other has the cadence of friends telling each other exaaaaaaaactly. She was one of the friends Lizzo didn’t push away, but SZA won’t take any credit for helping her through. “I think what’s special about my friend is she is a master healer. She is always going to get to the bottom of herself. Nobody cleared her name for her. Nobody could give her that vindication; she gave it to herself. I just felt like she 100 percent genie’d herself through that.”

The lawsuits are still active, and Lizzo continues to fight the allegations. Her legal team has filed multiple appeals to dismiss them to varying degrees of efficacy. She’s no longer an individual defendant in the case of the former wardrobe assistant, Asha Daniels, but her touring company still is. A trial is currently set for December. The case of the three dancers, Williams, Davis, and Rodriguez, has been murkier. Lizzo’s team has attempted to get it thrown out using the First Amendment and California’s anti-SLAPP rule, a law that allows suits to be quickly dismissed if they target free-speech rights — in Lizzo’s case, they argue, these lawsuits infringe upon her ability to promote herself and her music. A judge dismissed the weight-shaming allegation but denied the rest of the motion, allowing the case to proceed. In June, Lizzo filed an appeal, which is still pending. Davis, Williams, and Rodriguez declined to speak with me. Their lawyer, Ron Zambrano, said the chapter is not closed.

The late afternoon gives way to a dewy dusk. Lizzo’s Afro is Afro-ing. Someone cleared our lunch debris long ago, and K.C. has started prepping dinner. We’ve sat in the same position on a wooden bench for so long our hips are tight. Lizzo’s boyfriend, Myke, arrived about an hour ago for a planned guitar session. She stands, stretches, and goes to get him.

Lizzo has been taking guitar lessons for the past year, a double-duty task — Love in Real Life is real rock and roll, and she wants to be able to play guitar on tour, but she’s also preparing to play Sister Rosetta Tharpe in a biopic she’s producing with Amazon.

Myke hands her her acoustic guitar and gives her a kiss. The two met in 2016 when they co-hosted the MTV show Wonderland. They became romantic in 2021 and officially so in 2022. It was a “friends to lovers” trope, she jokes, “or maybe enemies to lovers.” It took them some time to lock into a steady relationship, and now, she says, “I’m really grateful to have someone who’s extremely supportive, who doesn’t ask for shit from me, nor does he need shit from me. He pours into me. He takes care of me.”

She starts strumming the intro to the title track, “Love in Real Life.” “Fuck,” she exclaims. She messes up and blames her long nails. She forgets a chord but keeps going, trying to trust that forgiveness is inherent in not being good at something you just started doing. Eventually, she finishes the song and beams. I applaud. Myke applauds. Lizzo’s smile demonstrates she’s applauding herself on the inside.

“There’s that smile,” Myke says proudly.

Bolstered by her ability to complete a song, she decides to try one more and places her fingers in the right position to launch into “Juice,” her hit single from 2019. It doesn’t sound quite right.

“No, this is wrong. Hold on, hold on. Oh, no. There we go. Okay, I’m gonna go slower. No. Oh my God. It’s the guitar. Exactly. I promise. I need a strap.”

Myke jumps in, adjusting a strap on her shoulder. “I can get the electric guitar,” he offers. “The electric guitar hides mistakes,” she replies, waving him off. She’s determined to battle it out with this guitar. She restarts. A few strums and then —

“Bitch!”

She lines up her fingers to try again.

In February, two months before we met, Lizzo announced a series of intimate fan shows in L.A., New York, and Minneapolis as a way of promoting Love in Real Life. (If it was a test to see whether she still had an audience, it was a good sign: The shows sold out.) On a rainy Sunday night in March, I approached a massive line in front of Irving Plaza. I stopped to ask two white 40-something women in sequined going-out tops and shimmery eye shadow if this was the line for Lizzo. An enthusiastic “yes” and then a pause as they took in how I wearily searched for the end. In a split second of silent deliberation (which I imagine went, She’s Black, we’re white! It’s the Lizzo show; are we taking up too much space?), they looked at each other, back at me, and offered to let me cut the line.

I took my place in front of them with a hearty “thank you.” “Karma,” one of them chirped in response.

It may be Trump’s America the sequel, but on line at the Lizzo concert, reparations are an active concept, even if we soften it to karma. I felt like Claire in the time-traveling romance Outlander, who is transported by mystical stones back to 18th-century Scotland. Stepping through the doors at Irving Plaza sent me straight back to 2019.

Inside, Lizzo’s fan base was dancing to a soundtrack of oldies: grown women on a girls’ night, a couple debating which era Lizzo was in now (one thought “ratchet”; the other insisted “bad bitch”), moms letting their sign-holding tween girls stay up after bedtime, awkward adolescents wondering if Lizzo was still body-positive even though she’d visibly lost weight (yes, they decided).

Lizzo came out in fishnets and a black leather jacket as the intro to “Love in Real Life,” her voice purring, “Everything was so much simpler …” Then she ripped into the opening electric-guitar riff of the song. She played all her hits — “Juice,” “Good As Hell,” “Truth Hurts,” ending on “About Damn Time” — and the crowd lost its mind at every single one. When she played another new single, “Still Bad,” the couple shouted to each other that they did enjoy Rock Lizzo.

For Lizzo, the March run of shows was a high-energy reminder of what it was like to perform for her fans, to knock the cobwebs off before the album release and the tour. But it also felt, almost, like attending a beloved star’s Vegas residency. There was a nostalgia in the air, or maybe it was a cultural disconnect. Her music seemed of a more earnest, innocent time. It was hard to comprehend how her message could still apply when the world had rotated away from her brand of hopecore and toward one of irony-poisoned, up-all-night-at-the-rave detachment. (“Kamala is Brat” made a bigger impact than Lizzo stumping for Harris in Detroit in the fall of 2024.) There was a danger of getting stuck in the past — no one wanted to end up like Katy Perry, who seemed perpetually in the Obama era. None of that seemed to matter much to members of an audience who had showed up to support her. They happily grooved their way through her feel-good hits.

Outside the Irving Plaza bubble, however, neither of her new singles, “Still Bad” or “Love in Real Life,” broke through the Billboard charts. “Lizzo’s New Single Debuts, But Its Arrival May Signal Trouble for Her Career,” read one headline. “When something like that happens, you start asking yourself the hard questions,” says Ricky Reed, Lizzo’s longtime producer. “What is it about these songs? What’s the story, why is the public reacting the way they’re reacting? And naturally, you start to get frustrated.”

Lizzo diagnoses the problem with those singles when we speak. “Still Bad” was “overproduced” and “overthought.” She wrote both songs in 2022. “By 2025, I’ve changed, the world has changed so much, and so much has happened,” she says. “And not that I felt disconnected from anything that I put out, because I created it, but it just wasn’t what I was feeling right now. I was like, I need to do shit differently and I don’t know what it is, but I’m going to just start following my instincts.”

Originally, she says, her “creative epicenter” for the album’s visual aesthetic had been the character of Marla Singer from Fight Club. “That final scene where Edward Norton blows up all the buildings dotting the skyline and he looks at her and is like, ‘You met me at a very strange time in my life.’ That image to me was like, Oh my God, I want to have fur coats and fake cigarettes and smeared eye shadow and eyeliner, and I want to be messy but getting it together, and I want to be a diva. You know what I mean? The destruction of the buildings to me felt very symbolic of how I felt on the inside and my personal life.”

Instead, she’d trusted the label, as she always had, to pick her singles, which set the tone for the whole project. After all, it had been right about “Juice” and “About Damn Time,” Lizzo explains, pointing to the way the whole stadium lights up when she plays those songs. But the new singles and their accompanying visuals weren’t in step with the Fight Club nihilism and fur coats she’d envisioned. “I had forgotten how to trust myself,” she says. “I think, musically, I have been on a path to losing myself for a long time.” At the Atlantic meeting, she says, “I sat down at the table and I said, ‘I need to do shit my way starting from now. And I need y’all to have my back. It’s going to be a little scary.’ And everybody agreed, and they said, ‘We got your back, whatever you need.’ ” By then, Atlantic had put a lot of money and resources into the album campaign, Reed says. “But they were down to see where it went.”

In May, Lizzo released a more stripped-down version of “Still Bad (Animal Style).” Mid–album launch, she seemed to be re-relaunching into something less produced and more feral. A new video for “Still Bad,” a run-and-gun romp recorded on an iPhone, captured her bopping around the city right after the Met Gala. She left the party in the custom Christian Siriano gown she’d worn on the red carpet and went from a slice joint to a drag show to an arcade where she accidentally broke a $500 Goku statue. It was a turning point for her creatively. The comments section on TikTok lit up: “Oh this is the Lizzo I remember.” She remembered, too: “Oh yeah, the point of this was to have fucking fun.”

When I left Lizzo’s house in the spring, I thought the album would arrive in the summer as planned and she would start to prep for tour. All through the release cycle, she’d be telling the story of her fall into darkness and her return to joy. How she had been down, but now, about damn time, she was back to feeling good as hell and still 100 percent that bitch. But over the next couple of months, I watched from afar as Lizzo seemed to put the album entirely behind her. She started posting on her private Instagram and TikTok, LizzoIRL, so she could talk to “the fans who are really following and really paying attention and stop trying to address the masses,” as Reed explains it. There were shades of a freer, more fun, more accessible Lizzo than had been out there for the past two years. She traveled. She partied. She stayed out all night dancing. She was drinking again. She was hanging out with SZA while she toured with Kendrick, hopping up beside her at the unofficial after-party to a Kaytranada show in Ibiza that went till 7 a.m., then joining her onstage in Paris.

I couldn’t tell if Lizzo was floundering, avoiding work, or doing market research or if her whole summer was extended album promotion. I finally get my answer in mid-August, months after we’d met for the first time, when I see her at a recording studio in Los Angeles. Dressed down in big camo shorts and a cropped SZA T-shirt, socks, and Birkenstocks, she pulls up a swivel chair and sits backward like a theater kid who can’t sit regular. She’s more energetic and less introspective than when I saw her in the spring. Her answer is simple: “The old me would be like, ‘No, I don’t want to drink. I don’t want to go out.’ ” But she’s decided “I owe it to myself to be outside. I worked hard getting my mental health back to a place where I could enjoy being in my body and with my brain. I worked hard to look this fucking good. I’m going to be outside, and I’m going to shake my ass on a yacht in Ibiza.”

During her summer of outside, she began to find new sources of inspiration. She became obsessed with young female rappers coming out of Atlanta, who were fearless and experimental and unvarnished, untethered by expectation or label pressures or release cycles. Lizzo latched on to one boisterous anthem in particular, “Whim Whamiee,” by Pluto and YKNiece. She added her own verse to the song and put it up on TikTok, where it went “fucking crazy,” and sent it to the label as a proof of concept. With their blessing, she says, she went on to make music that wasn’t for the album. “Love in Real Life was about a lot of pain and seeking joy and going through being fucking suicidal and depressed,” she says. “And feeling like the world has turned their back on you and then finding your way back into the world. It was beautiful, but ain’t nobody trying to hear that shit right now.” On her private Instagram, she posted an exchange between herself and an unspecified person. “I’m changing my whole album,” she wrote, followed by a shhhh-face emoji. She didn’t end up changing her album, but she’d decided on her next big move.

Lizzo flew in her besties. She rented studio space for five days. Reed came in, and they commissioned beats from producers for her to rap over. Frequent Gucci Mane collaborator Zaytoven gave her three tracks and came to the studio to work with her, bringing new energy into the room. Every day from noon to midnight, they would “listen to beats, talk shit, listen to beats, talk shit. Repeat. Talk about food, then eat the food, then talk about food while we eating the food. Go back to the song.” They drank wine and tequila. She started eating the same meal she ate when she was broke in Minneapolis and had to ask her mom to send her money so she could buy a Jimmy John’s turkey sandwich with extra cheese and pickle chips. It was her Proustian Jimmy John’s sub, taking her right back to being a scrappy musician. She recorded 17 songs in five days and released 12 of them in June as a mixtape, My Face Hurts From Smiling, hoping to capture something raw and urgent. Genrewise, the mixtape is highly quotable rap music built for TikTok, not for longevity. On “YITTY ON YO TITTIES (FREESTYLE),” she drops the line “How you talkn shit bout me, can’t even outdress my Labubu,” a lyric that launched a thousand TikToks of people showing off their well-dressed Labubus. (Lizzo’s is riding shotgun on her Birkin bag today.) She followed it up with a deluxe version of the mixtape My Face Still Hurts From Smiling that dropped suddenly in September and features more house-influenced tracks that reference ChatGPT, Love Island, and eating ass. One song directly takes aim at “the discourse.” (It’s called, subtly, “STFU.”) Lizzo may not be emblematic of an era in the way she once was — she may not even be trying to mean anything at all — but she’s certainly diving into the pool of whatever is current and seeing if she’ll swim.

“I think I needed to drop those songs so I could subvert that expectation of me,” she says, “because, in turn, it created this new discovery that I really wanted. I wanted people to rediscover who I am and fall in love with her all over again.” If you look closely at the cover of My Face Hurts From Smiling, Lizzo is standing in front of a hanging tapestry embroidered with what would have been the cover of Love in Real Life. It’s symbolic, in case you were wondering. “I was like, Get behind me, Love in Real Life; I got this,” she tells me. Currently, the album’s release date is indefinite. “TBD,” Lizzo responds when I ask what will happen with it and the tour.

Before she changed directions, I heard a few of the new album’s unreleased tracks, and while the songs tackle the angst and hardship that shaped her past couple of years, they are still sonically Lizzo. On “Happy 2 Be,” she sings about overcoming depression. “Bitch,” which samples Meredith Brooks, is basically shadow work with singing-in-the-car-with-the-windows-down energy. There’s a song to help you get out of bed in the morning and feel good despite it all (“Goodmorning!”). I ask Lizzo if fans will ever hear the album or if it will remain a “buried treasure,” as Reed calls it. Another TBD. “They had the commercialized version of me — the packaging, the market, the brand,” she says. “But the only way I could have expressed what I’m expressing was through the medium of rap.”

Lizzo had started to feel like Melissa Jefferson again, the artist who started out as a rapper. She was in her bag, she tells me, triumphant, and she’s trusting her real fans will meet her where she’s at. But if they don’t? “I’m in one of the most exciting, creative flows I’ve had as a human being on this planet. Who cares if you don’t like it, bitch? I got 7,000 more songs like it. This ain’t the only album I’ll ever do. This ain’t the only song I’m going to ever sing. Bitch, you can’t get rid of me!”

Production Credits

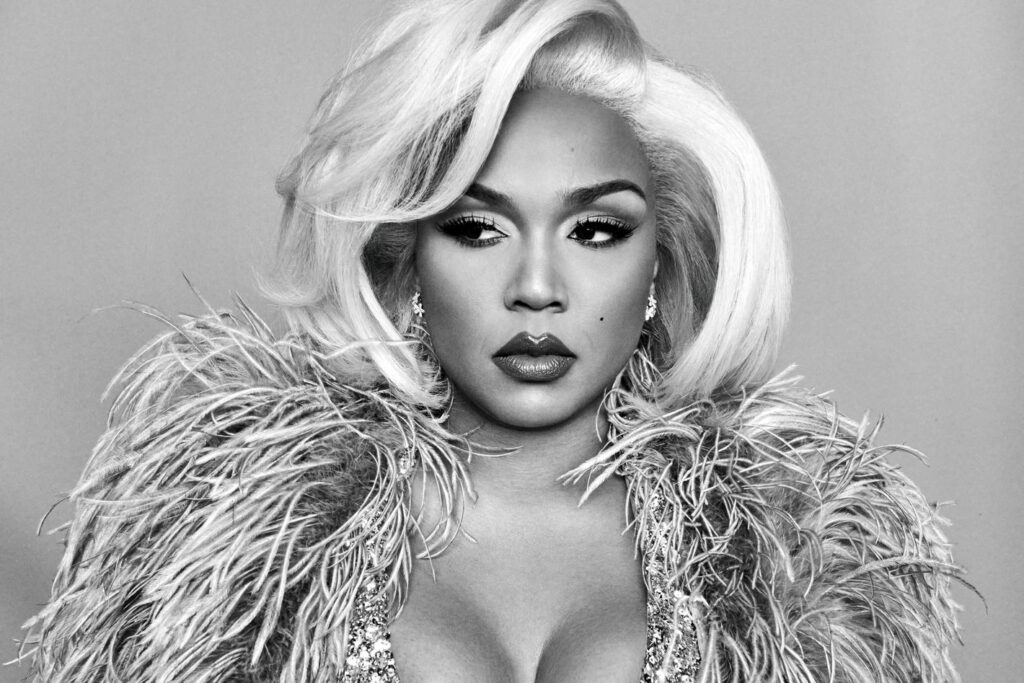

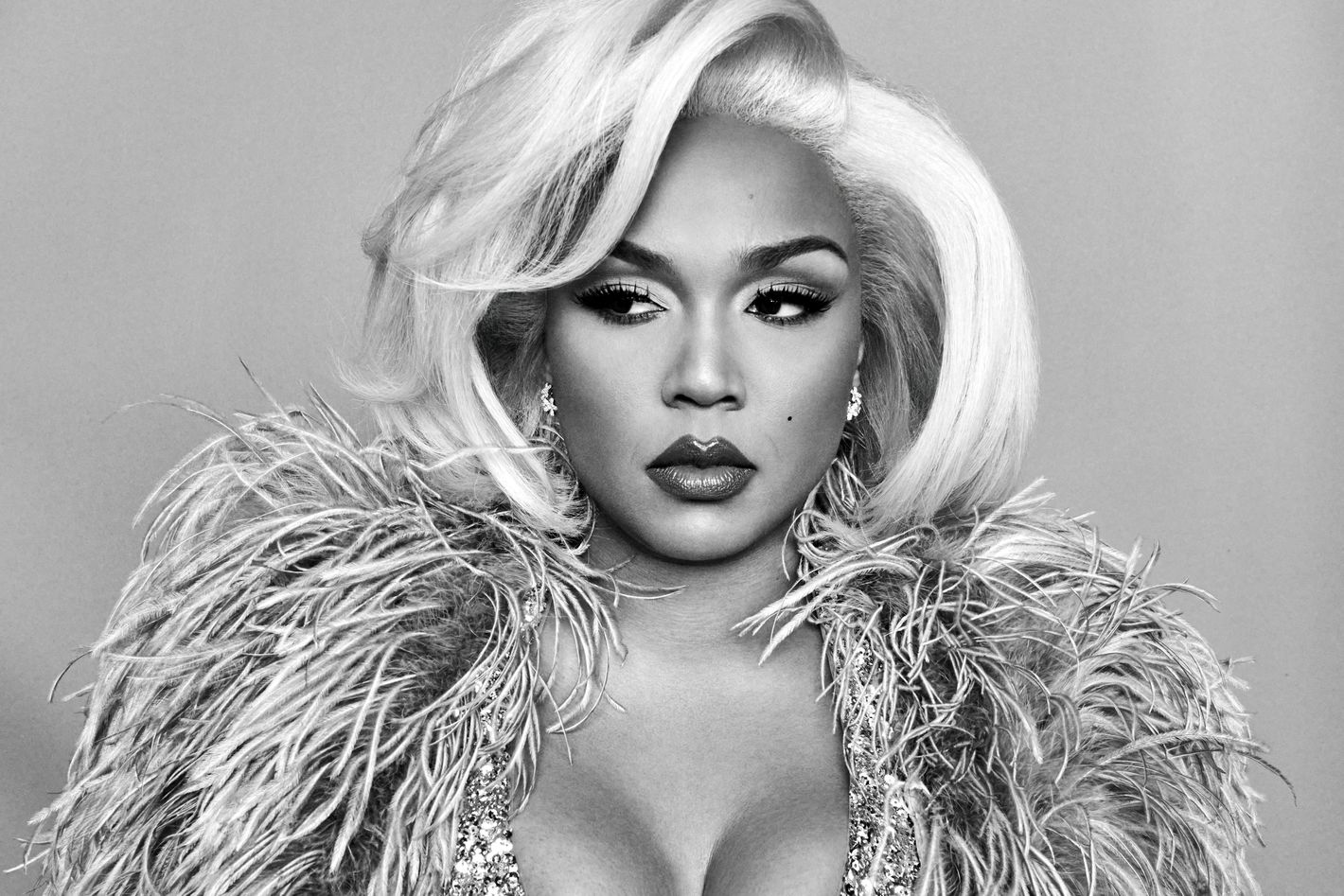

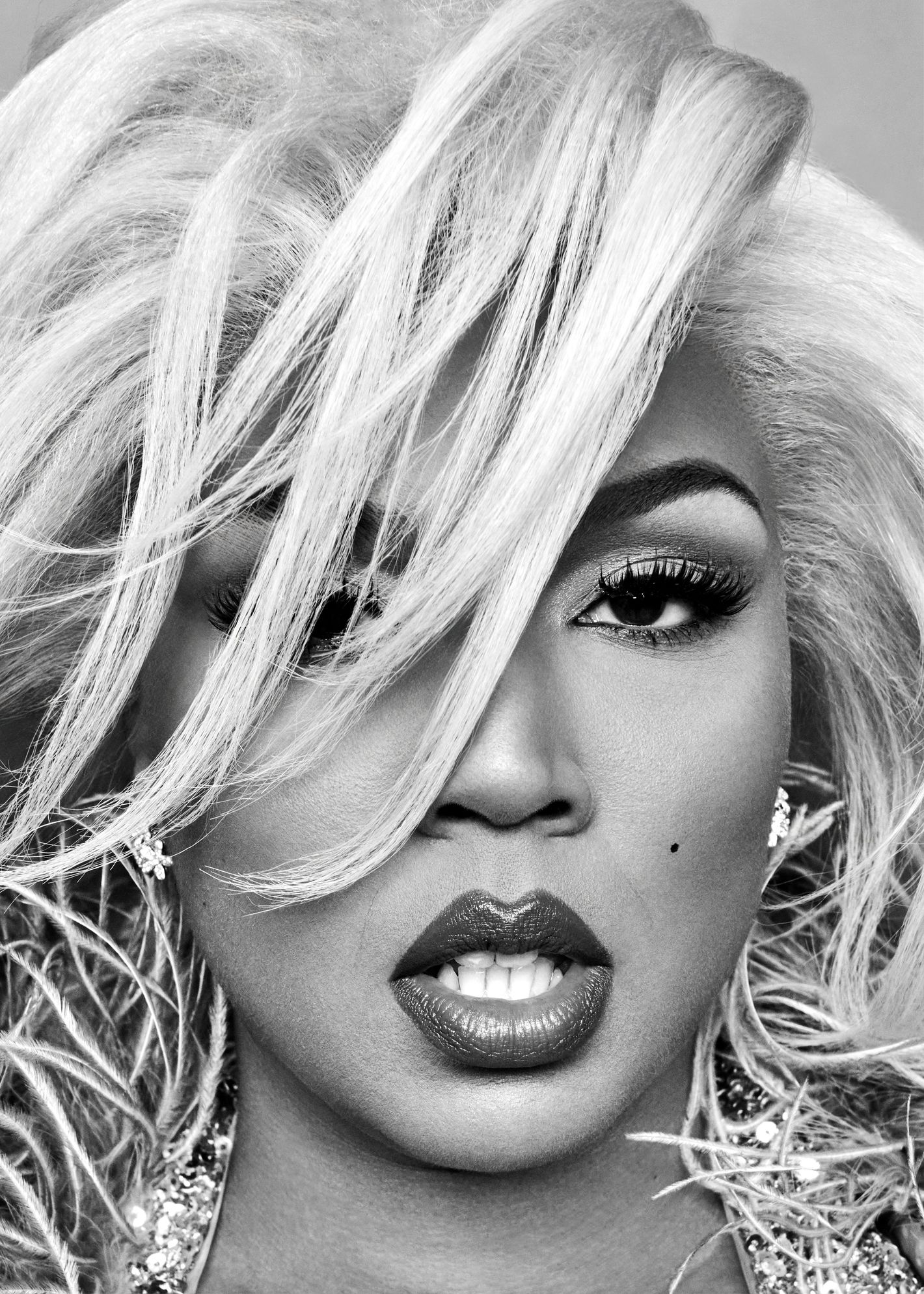

Photographs by Ruven Afanador

,

Styling by Wayman + Micah for The Only Agency

,

Hair by J Stay Ready at Chris Aaron Management

,

Makeup by Alexx Mayo using Dream Labs for The Only Agency

,

Manicure by Eri Ishizu at The Wall Group

,

Tailoring by Lindsay Wright

,

Special thanks to The 1896 Studios & Stages, Primate Props

,

Dress by Halston

,

Stole by Adrienne Landau

,

Shoes by Aquazzura

,

Earrings by Van Cleef & Arpels

More From Fall Preview

The pop star’s success once felt radical. Can she capture the zeitgeist again?