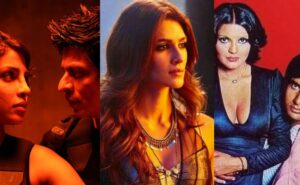

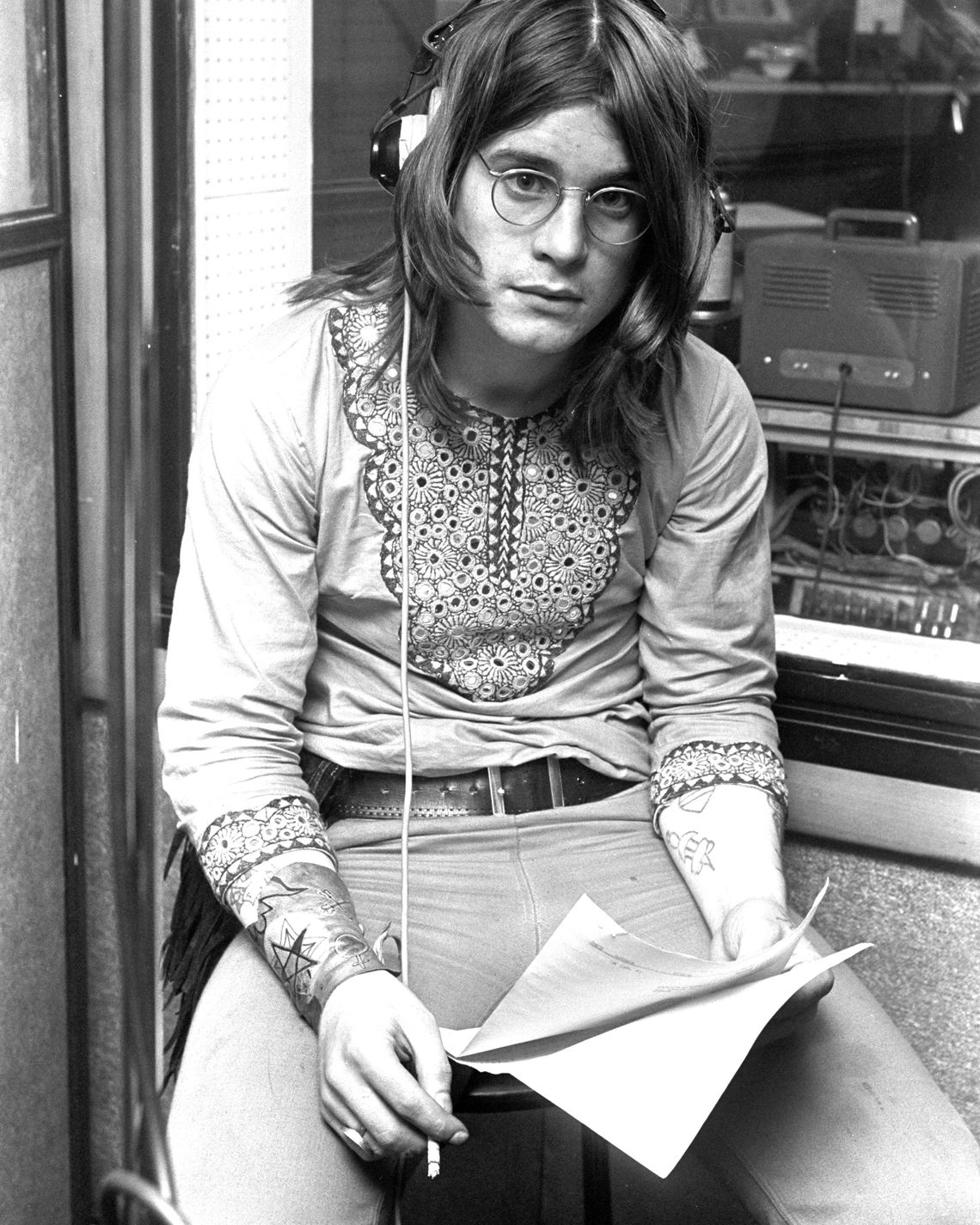

If you polled the public about Ozzy Osbourne in the 1970s and ’80s, you were likely to hear he was a self-destructive rock-and-roll hedonist, a literal emissary of Satan, or a first-ballot contender for coolest and craziest human alive. Black Sabbath, his coterie of paradigm-shifting Birmingham blues rockers and bar brawlers, cultivated a taste for demonic iconography that was as off-putting to normie sensibilities as the gritty tones and discomfiting tempos explored in the hard-partying quartet’s music. Named after a horror film they never saw, the band broke big by carrying rock excess into new territories. They one-upped the burgeoning hard-rock movement of the late ’60s in pure ominousness, distortion, and overindulgence. Black Sabbath formed out of desperation and mutual convenience at first. Osbourne put an ad in the paper as a local singer in need of a band. Guitarist Tony Iommi and bassist Geezer Butler were equally hungry for a way out of Birmingham, but Iommi worried that this class clown a few years behind him in high school wasn’t built for the business. But with drummer friend Bill Ward in tow, Iommi soon learned that the loopy restlessness of Osbourne, who was by then a convicted thief and aspiring burglar, came with a howl soulful and baleful enough to fill their drowsy blues and chthonic camp with relatable angst.

Osbourne, who died on Monday at 76, became a more multifaceted and adaptable thinker than early observers would’ve guessed. Incremental and savvy career adjustments made for a compelling pop-cultural figure over decades. But in Sabbath’s early days, there was no internet to explain that the guy running around calling himself the “Prince of Darkness” wasn’t conducting blood sacrifices at concerts; and there was little context for the acting out people were seeing, for a learning-disabled member of the postwar English downtrodden who saw showmanship and crime as his two pathways to escaping the bombed-out Midlands. Sabbath wasn’t the only pivotal act present at the birth of metal, but others didn’t inspire as many outlandish tales or as vast a collection of die-hard fans. Ozzy was crowned as the genre’s spokesperson, mascot, and lightning rod. He changed metal forever, but he also stuck around as it evolved further, helping to foster growth.

While the other proto-metal jams fixated on good times and romance, “Black Sabbath,” the opener to the band’s 1970 eponymous debut album, offered a grisly stage play about entertaining dark forces. Butler, Sabbath’s primary lyricist, had been reading books about magic when he encountered what he felt was a sinister presence in his home one night. Ozzy turned the tale into a study of gloom: “What is this that stands before me? / Figure in black which points at me.” Iommi added the diabolus in musica, an eerie tritone musical interval denounced as unholy and dangerous since the Middle Ages. Using the arguable sound of evil on the song gave the band an imposing reputation. “I don’t remember where we first played ‘Black Sabbath,’” Osbourne recalled in his 2009 autobiography, I Am Ozzy, “but I can sure as hell remember the audience’s reaction: All the girls ran out of the venue, screaming.” Stalked by Satanists and feared by Christians — both believed the hype — Sabbath met a rock-critic sphere that didn’t respect the band’s corroded and drunken debasement of ’60s blues rock but could at least tell they were taking the piss. “The album has nothing to do with spiritualism, the occult, or anything much except stiff recitations of Cream clichés,” Rolling Stone’s Lester Bangs quipped.

But the menace served a message. That diabolical racket was antisocial but also antiwar. The devilry was often cautionary. “Black Sabbath” advised people to “beware,” and “Lord of This World” from 1971’s Master of Reality critiqued human depravity from the devil’s perspective: “You made me master of the world where you exist / The soul I took from you was not even missed.” Like Houston screw music in the ’90s, Sabbath’s debauchery fueled exhilaratingly dark and slow grooves. People who could see innovation in a seemingly unprofessional sonic approach, and who got that the gloom was mostly the feisty wallpaper for it, carried the torch further. The band’s macabre theatricality pricks up in the advancing madness of shows from hard-rock staples like Alice Cooper throughout the ’70s and the plummeting tempos that would inform stoner rock and sludge metal later on. Sabbath and Ozzy were too volatile a combo for their own good, though. The experimentation and antics that had built the band drove a wedge between them. Sabbath fired Osbourne in 1979 after he slept through a show in the wrong hotel room, leaving his friends and fans to assume that he’d died.

Ozzy seemed at once incapable of death and hopelessly in search of it. Having cheated real mortality across dayslong ’70s benders, he avoided the end of his career just as astoundingly in the ’80s when he reemerged as a solo artist alongside former Quiet Riot guitarist Randy Rhoads at the urging of Sharon Arden, daughter of pushy rock manager Don “Mr. Big” Arden. The unlikely reversal of Ozzy’s fate —“I was unemployed and unemployable,” he lamented in his autobiography — is doubly notable for wrecking the Ardens’ relationship; Sabbath was Big’s band, and Sharon’s play to save the vocalist’s career, along with her developing romance with Ozzy, scanned as familial betrayal. But cutting ties with the old band and team proved to be instrumental to Osbourne’s next chapter. With a more hands-on role in the music outside Sabbath, where there wasn’t as much room for his pen or his pop instincts, he struck an unruly balance between the cartoonish evil of old and an under-explored softer side.

1980’s Blizzard of Ozz initiated a renaissance. The massive hit single “Crazy Train” touted Rhoads’s blazing guitar and quieted questions about whether Ozzy was finished without Iommi; the sweet “Goodbye to Romance” hinted at the imminent hair-metal explosion that “Mama, I’m Coming Home” and “Close My Eyes Forever” assertively dip into later on. Ozz held court with metal music borne of the blitzing pace of Sabbath’s “Paranoid,” from the band’s second album, and slow, sleazy hard-rock toasting to sex and debauchery. The records he made with Rhoads brought Ozzy’s voice in contact with the wider world of heavy music that his first decade of albums inspired, appealing to longtime fans while carefully engaging with evolving British and American rock-song forms. But the madman image endearing him to metalheads and casual rock fans served a gourmet platter of fear to a furtive satanic panic: He dressed in priest’s garb on Ozz’s cover, dedicated a song to occultist Aleister Crowley, and bit the heads off doves and bats at his shows — all of which led to accusations from religious groups and grieving families that his songs were driving fans to commit murder and suicide.

He wasn’t the prophet of damnation they portrayed in the ’80s, but he wasn’t demonized for no reason. He was living outrageously enough at his creative peak and well afterward to warrant concern, jeopardizing more than just his own well-being. Substance abuse and infidelity eroded his relationship with his first wife, Thelma Riley, and their children throughout the ’70s. And he was arrested for attacking and threatening to kill Sharon while blackout drunk in 1989. It was a reasonable conclusion to draw that this person was out of control; it was also quintessential fanciful ’80s to attribute the root of the problem to him being possessed. The backlash from conservatives about Satan died down a bit as the raunchy ’90s settled in, though. So, too, did a sense within the industry that Ozzy was a contemporary musical commodity.

Unexpectedly, we have Lollapalooza to thank for Ozzy Osbourne’s subsequent reinvention. Sharon pitched him to former Jane’s Addiction front man Perry Farrell’s seminal traveling alternative-rock showcase around 1995’s Ozzmosis, which maneuvered out of the glam adjacency of 1991’s killer No More Tears. When Lolla didn’t deem him a sufficient enough draw, the Osbournes set out to get the festival to wish it did. Ozzfest, which launched in 1996, made use of Sharon’s connections, Ozzy’s still-regal standing in his community, and their son Jack’s nü-metal taste to build a lineup catering to the kind of coarseness that Lolla highlighted too infrequently. The next few years bore out whose vision of the coming century rung truest: Lolla struggled to stay on the pulse of the late ’90s, taking a long hiatus as Ozzfest became one of the must-see summer metal tours of the turn of the millennium.

In 1997 and 1998, the festival put Ozzy’s past in collision with rock’s future in alluring but also concerning displays. A reunited Black Sabbath brought Limp Bizkit, Incubus, and System of a Down around the country capturing each act on the cusp of a star turn in the early aughts. But before a 1997 date in Columbus, Sharon tossed Ozzy’s Vicodin and he refused to get off the plane and perform, sparking a riot that left terrified fans, brushfires, and a wave of property damage in its wake. The incident said Ozzy could still be a liability to himself and others, and presaged the flammable flashpoint two years later at Woodstock ’99. Ozzfest beat on without commensurate incident and alumni racked up platinum records in the extreme metal outpouring of the early aughts, but it took much more effort to tilt the public’s view of Ozzy Osbourne.

The MTV reality show The Osbournes succeeded beyond anyone’s loftiest dreams at rehabilitating Ozzy’s image by zeroing in on something apparent all along if perhaps obscured to people unaccustomed to his Brummie accent: He was one of the funniest people alive both when he was and when he wasn’t trying to be. This was a constant from early Sabbath footage where he jumped around creating a spectacle an audience could never forget to spilling orange juice all over the table while explaining that his wild days were mostly behind him over breakfast in Penelope Spheeris’s 1988 documentary, The Decline of Western Civilization Part II: The Metal Years. He hammed it up hard enough in the ’80s videos to land in Beavis and Butt-head rotation. His autobiography is wall-to-wall jokes in spite of the life-threatening subject matter. The Osbournes, set in the family’s L.A. home in the early aughts, deflated the patriarch’s imposing public perception, revealing a noisy life beset by his sullen teens, wife and wrangler, and everyone’s zany dogs.

Reality TV had enjoyed a decade of water cooler banter in America for viewers of Real World age by the time the metal brood got there in 2002, but it wasn’t long before Ozzy, Sharon, Jack, and Kelly were household names. The show gave captivating insight into the warring brain trust that nudged Ozzy back to greatness whenever his star dulled and his confidence dimmed. Watching the doting father defuse sibling fights humanized the lunatic of “Paranoid” and “Crazy Train” who pissed on the Alamo, fed a vicar a knockout hash brownie, and got screamingly hammered at the 2002 White House Correspondents’ Dinner. The beating heart behind the bat-biting facade was plain to see, and he came to bask in the same genteel rock grandfather stature as the remaining Beatles, whose second album put the idea of being in a band in his head in the first place.

Two weeks before his death, Ozzy played his final show, Back to the Beginning, which was also Black Sabbath’s last. Everyone from Metallica to Jack Black to 27-year-old singer and actor Yungblud performed — a testament to Ozzy’s never-ending quest to commune with and nurture new sounds. He wanted to be on the bleeding edge of music, from itching to outdo Robert Plant in the ’70s to granting features to rappers like Busta Rhymes in the ’90s. Osbourne’s resurgent recent work like 2020’s Ordinary Man was making clever and even affecting use of an intergenerational cast of characters that included Post Malone and Elton John. Losing Ozzy so soon after his farewell concert leaves the impression that the man literally lived to entertain. “Me and Geezer were talking about it last night,” Iommi said in a Wednesday ITV interview reflecting on Back to the Beginning, “that we think he held out to do it.” Ozzy said good-bye to us as he lived, surrounded by musicians he inspired with the giddy light of love piercing through the obsidian veneer.

Related

- Ozzy Osbourne Always Had No Filter

- Kermit the Frog Pays Tribute to his Friend, Ozzy Osbourne

- Ozzy Osbourne, Black Sabbath’s Prince of Darkness, Dead at 76

He birthed what many consider the sound of evil. His image was constantly working for and against him.