In a run-down corner of Athens, two cousins hover in a park square, looking for tourists to steal from. They are refugees and scavengers, part of a community of Palestinian men whose pasts share many of the same hallmarks: childhoods spent in Syrian and Lebanese camps; separations from family while trying to make a “better life” in Europe; poverty, famine, and homelessness. But the desperation that Chatila (Mahmood Bakri) and Reda (Aram Sabbah) live with in filmmaker Mahdi Fleifel’s To a Land Unknown has made ethnic bonds tenuous.

This is personal for Palestinian-Danish director Fleifel, who grew up in Lebanon’s Ain el-Helweh refugee camp, created after the Nakba to temporarily house Palestinians living in exile from their now-stolen homes. What was supposed to be temporary became permanent, and generations of families eventually lived there. It’s the largest Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon, housing more than 60,000 people, according to December 2023 numbers from the United Nations. Fleifel began his career with the 2012 documentary A World Not Ours, which drew upon his archive of videos from his visits home to the camp and followed a childhood friend who eventually left Ain el-Helweh for Greece. In the intermittent years, Fleifel directed a number of short films about Palestinian culture and history, including 2015’s 20 Handshakes for Peace and I Signed the Petition, alternately furious and searching explorations of how exile alters political opinions and changes personal priorities. Like To a Land Unknown, those films are littered with references to Palestinian thinkers and artists (academic Edward Said, poet Mahmoud Darwish), honoring the diaspora’s cultural sprawl.

Fleifel reuses some of those techniques in To a Land Unknown, his first feature-length narrative film. (The movie is currently in limited release and will expand nationwide in coming weeks.) A quote from Said about Palestinians being fated to end up “somewhere unexpected and far away” appears onscreen in the opening minutes after a montage that ends with Chatila and Reda staring into the camera. A character who initially seems like a scumbag gains instant interiority by reciting excerpts of Darwish’s 1983 poem “In Praise of the High Shadow,” written while Darwish was living in a besieged-by-Israel Beirut. This time paired with co-writers Fyzal Boulifa and Jason McColgan, Fleifel also examines how statelessness transforms people and whether second chances are possible under geographically striated circumstances, questions that become guiding motivations for the cousins.

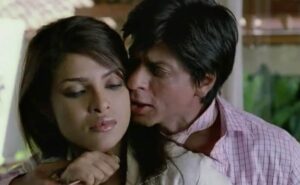

Chatila is street smart, strategic, and ruthless; Reda is softhearted, doe-eyed, and self-destructive. They bring to mind the opposites-attract protagonists of the seminal Palestinian film Paradise Now, about two childhood friends preparing for a suicide bombing. But they also aren’t dissimilar from Keanu Reeves and River Phoenix’s characters in My Own Private Idaho or Al Pacino and John Cazale’s in Dog Day Afternoon — men who complement and contradict each other and who understand and need each other more than anyone else. The backstory for each cousin is brief, provided mainly through phone calls back home to the Lebanese refugee camp where they grew up: Chatila left a wife and young son behind; Reda’s mother is worried her son will slide backward into a dangerous addiction. Certain details about their lives invoke Palestinian history, like when the Greek woman Tatiana (Angeliki Papoulia), with whom Chatila engages in a self-serving flirtation, calls his name girlie. Chatila responds to Tatiana with a grim smirk, which on the surface seems like masculine posturing. She doesn’t know that Chatila is also the name of a Palestinian refugee camp in Beirut that was the site of a 1982 massacre perpetrated by a right-wing Lebanese militia and the IDF; thousands of Palestinians were killed over nearly two days while exits from the camp were purposefully blocked.

To a Land Unknown doesn’t explain that moment for unaware viewers. But for those in the know, it’s another way in which the film’s melancholy milieu feels urgently tied to the present, ongoing destruction of Gaza and the increased violence in the West Bank — and supports Fleifel’s thesis that displacement is the first step in the murder of the human spirit. As Chatila and Reda scheme to leave Athens for Germany and dream of opening a café together, they resort to false identities, hostage-taking, and lies upon lies upon lies that hurt them as much as anyone else. When the friends finally reach a point of no return in their relationship, Bakri plays the disruption with savage enterprise and Sabbah with wounded silence, realization dawning on his face that Chatila, the man he considers his closest ally in the world, sees him as just another body to be taken advantage of. It’s an unforgettable bit of acting from both men, and it gives the film’s turn into thriller territory real potency. (Nadah El Shazly’s synthy, foreboding score aids that genre shift.)

To a Land Unknown doesn’t try to argue that everything Chatila and Reda do is justified. But in quoting Darwish, the film brings to mind another of the poet’s verses, from 2002’s “A State of Siege”: “Under siege, time becomes a location / solidified eternally / Under siege, place becomes a time / abandoned by past and future.” Chatila and Reda are stuck in a time and place where they’re treated like ghosts, cursed to haunt the streets of a city where people choose not to see them. To a Land Unknown presents the cousins’ ordeal as something no person should have to go through, something unnatural and surreal and Kafkaesque. But there’s also a creeping devastation in how the film convinces us of their pain and of all the opportunities and chances that were stolen from them through statelessness. The absurd thing would be to ignore it.

More Movie Reviews

Filmmaker Mahdi Fleifel’s portrait of Palestinian cousins stuck in Greece is a devastating examination of how statelessness transforms people.