The Doobie Brothers have walked, run, and smoked down the highway for a very long time. Over 50 years of mileage, to be exact. Patrick Simmons, the band’s co-founder and sole continuous member, has been there for every pit stop. And what a great highway the Doobies have found themselves riding this month: The band’s newest album, the appropriately titled Walk This Road, has been released — serving as the first time Simmons, Michael McDonald, and Tom Johnson have collaborated in the studio together. (It’s so good, even a fool could believe it.) The trio is also entering the Songwriters Hall of Fame on June 12 for their contributions to the classic-rock canon, representing the several Doobie strains, from “Listen to the Music” to “Minute by Minute” and beyond. If there was a bit of sibling rivalry in the past between the different iterations of the band, it’s over now. It’s all about good vibes and passing one around if you feel like it. “After decades of pushing that message,” Simmons says, “we’re still on that path.”

Song where you found your groove

I played the solo on “Listen to the Music,” and that was a big moment for me in terms of my lead play. Tom and I both played lead guitar, but I always deferred to him because I thought he was such a great lead player. I deferred to him often because I just liked his playing and thought he was maybe a better player than I was. When we recorded “Listen to the Music,” we got to the end of it and I was trying to think of something that we could lift it up a little bit. That’s always been my approach to production: Okay, you’ve gone this far in the song and now you’re at the end. What can you do here to ride it out? What can you do to lift it to just a little bit higher than where it is right now? So I threw a guitar solo on that song and I wasn’t sure about it.

That was the first lead I’d ever played in the studio on a Doobie Brothers record. I’d played plenty of rhythm and finger-picking stuff, but nothing of this scale. I played that solo and Ted said, “I love that. It takes the song to this other level that you were talking about.” So the solo ended up on the record, and that was the moment I finally said, Wow, there’s a place for me here as lead guitar player that I’ll be able to express myself within the band structure. It gave me another avenue and a feeling of possibility.

Ideal album to smoke a doobie to

I always think Livin’ on the Fault Line was the craziest album we ever did, and it’s arguably my favorite record. It had a lot of oddball sounds and some crazy solos — a real change-up from song to song, from almost fusion-y stuff, to straight-ahead R&B, to country. There’s all kinds of weird combinations of music on that record that could enhance the experience. I think it’s an illusion that you become more creative by getting stoned. I think I’ve written some of my best songs, at least more recently, when I wasn’t stoned. I tell you what it does: It makes you continue the process longer. So there’s an aspect there of helping you to stay focused on something.

Biggest recommitment of an album

This had to happen more than once. Toulouse Street was a huge recommitment. That was our second record. We had done one album for Warner Bros., and, well, it wasn’t a failure, but it didn’t live up to the expectations we had hoped for. We didn’t have any hits or get much radio play. Musicians always have their hopes up — hoping for some kind of recognition or connection with your audience, whatever. We didn’t get that with our first album. And then Toulouse Street was another chance to do another record. We were on the verge at that point of being dropped from the label. We had gone in and tried to produce some songs on our own and failed miserably. We spent a lot of money. Ted Templeman came to our rescue and said, “Let me try this again with you guys.” He took us in and was our saving grace. They gave him and us another chance, and we were able to come through, write better songs, and become more of who we really were, which was a rock-and-roll band. Prior to that, I think we were seen as more of a folk or acoustic band, kind of a “lighter touch” band. But we saw ourselves as rock and blues guys, and Ted was able to see a clear vision of who we were.

The next recommitment was Takin’ It to the Streets, where we had to change our direction because of Tom’s leaving the band at that time. It wasn’t something we were expecting, to be honest with you. It was more something that just happened. That’s been a certain saving grace for this band: We’ve been lucky to land on our feet, even in troubled times. That was one of those times where we really didn’t know what we were going to do. By virtue of hiring Michael to be a sideman and sing background vocals for us, we discovered a huge talent — a megatalent. Then we came back after a decade of working with Michael to where we are today with Cycles. That was our first reentry period in the late ’80s, and we’ve been working ever since. We’re not having a huge number of hits or anything, but we’re certainly enjoying our careers, having fun with the music, and still writing and producing stuff that we feel good about.

Song that proved you wrong

“China Grove.” It, of course, became a big hit for the band. It’s not that I didn’t like it or anything, I just didn’t think it was the song that would become a hit. At that time, I was probably over-intellectualizing everything. My comment back then to Tom was, But the Chinese don’t have samurai swords? Now, I look back and laugh because it wasn’t about samurai swords. It was more of a tongue-in-cheek poking fun at a redneck town that was full of Chinese cowboys in Texas. It was a parody in a sense. I had to eat my words on that one. It’s a really fun song to play because it’s not super-complicated with its chord structure, but it has a clever riff.

Tom had purchased an Echoplex around the time we recorded “China Grove,” which was a continuously running little piece of tape that gave you the echo effect. When we got to the studio to record the song, the producers forgot to use the echo effect. They played the song back for me and I said, “Hey, where’s the effect?” And Ted looked at me and responded, “Oh my God, I forgot to put it on the track.” So we went back in and put the echo on the track using a more sophisticated machine to achieve the same effect. The light really went on for me when the song started to get a lot of radio play, and then when we played it live, people went nuts. It was one of those moments where the crowd would go crazy and they still do. We always put it strategically in our set to have the crowd go from enthusiastic to wild.

Essential song for understanding the band’s brotherhood

Our current song, “Walk This Road,” is what that’s all about. In fact, one of our producers came in with the idea for the song and said, “You guys have been together for over 50 years and I feel like you’ve all been walking this road all this time.” Michael took hold of it and said, “Yeah, I get that,” and wrote the rest of the song. More than probably any other song that we have, “Walk This Road” is about our journey and our commitment to one another.

Most unifying song

“Listen to the Music.” That was a unifying song in terms of the message that Tom was expressing. We all agreed with everything in that tune: Music is a unifying art form and we need that kind of unification. Then I would also point to “Takin’ It to the Streets,” which is another song with a similar view, certainly with a more gospel-roots presentation. Michael was talking about the problems between the races — not even really between the races, but the infliction of hardship upon people of color and that struggle. It was certainly on the side of unification and bringing people together. It’s something we promote continuously and always have.

I think it lies more in the genre than it does in the message. Our music is mostly R&B based, or soulful music, if you will. At least that’s our intention. That’s implied throughout all the music we present. We’re carrying that message of music onto present and future generations. It’s an expression of social consciousness, and that consciousness is complex in its derivation. It comes from Black music, it comes from white music, it comes from more countified music, it comes from gospel music, and it comes from religious music. All the different kinds of music you can think of, from jazz to country, from blues to classical, we’ve been influenced by. So, in that sense, our songs are an expression of the tapestry that is America, and it’s way more than any of us can imagine. It’s certainly being compromised at this moment, but the music will never be compromised. You can’t change that. Even the people within the music community who are separatists or whatever within the concept of our social structure, they’re part of that deeper tapestry that they themselves may not even recognize.

Song most misattributed to the Doobies

“Drift Away,” which was made popular by Dobie Gray. I’ve had so many people come up to me and say, “I love your song ‘Drift Away.’” I even had a lady come up to me and go, “Look, I got a tattoo of your beautiful song.” And it said, in permanent ink, “The Doobie Brothers, Drift Away.” I didn’t have the heart to tell the woman about her error. But I’m still laughing about it.

Song that would rev up the Hells Angels like no other

“Jesus Is Just Alright With Me” was the one that got to those guys. I can only surmise that deep down in their hearts, as in probably all the hearts of outlaws, there’s a hope for redemption. And the fact that we were this greasy rock band — hill guys — we could bring the word to them and they had the possibility of that redemption.

We played a club one night in Palo Alto and did “Jesus Is Just Alright With Me.” It was a night where Gregg Rolie was sitting in with us, from Santana. He had come down to this club we were playing at, and he really liked the band, so he brought his organ and set it up and said, “I want to sit in with you guys.” Of course, we couldn’t refuse Gregg Rolie. We hadn’t even done our second album yet, but we were doing the song in our set — we did a little more elongated version of it where it turned into a jam. That night, we played and finished the song, and this gigantic Hells Angel came up. He had already threatened me early in the evening with, “If you don’t give me some cocaine, I’m going to beat the crap out of you.” So we finished “Jesus Is Just Alright With Me,” and that same guy walked up when we finished and went, “You guys should play that again. I love that song. Play it again.” So we launched back into it. I didn’t want the crap beaten out of me. But we had a great relationship with those guys, luckily for us. We were all aspiring bikers, loved the lifestyle, and could totally identify with it.

Song you had to fight the hardest for

The most difficult process we went through as a band was Minute by Minute. There was so much uncertainty going through with the songs, the arrangements, and the recording. For myself, I was in this completely uncertain place with our career at that point. Where is it going? Our previous record, Livin’ on the Fault Line, wasn’t a very successful album for us. We were regularly selling more than 1 million records going out the door with our previous records, and with that we sold about 200,000. So I was a little unsure of where we were going to go and where we were going to land. Though I loved the songs and felt really good about the music, Michael and our producer were unsure about his songs. And then the record company was unsure.

I spoke with various people who said, “How are we going to market this? What’s the record?” And I kept saying, ““What a Fool Believes.’ ‘What a Fool Believes.’” And they went, “Nah, that’s not the one. We think it’s another song. Or maybe we should take a song off a past album and release that instead.” And I kept going, “No, it’s ‘What a Fool Believes.’ It’s going to be a hit. It’s the most promising song on the record. You’ve got to release that.” They weren’t going to do it. I had to really push hard to get that song released. They wanted to do “Minute by Minute,” which is a great song, but it would’ve been a mistake to make that the lead single. At that point, we were right in the middle of the disco era and the Bee Gees had just put out Saturday Night Fever. It was good to have a song that had a great rhythm section and a cool complex. The rhythm on “What a Fool Believes” is just excellent. It was well worth the battle.

Song infused with the most Steely Dan spirit

“It Keeps You Runnin.’” It’s a simplistic chord structure and has the “circle of fifths” perfection that appears in Steely Dan songs. I wrote that song, and it’s a zingy kind of fusion-based track. It represents that marriage of jazz idioms and blues that Steely Dan was known for.

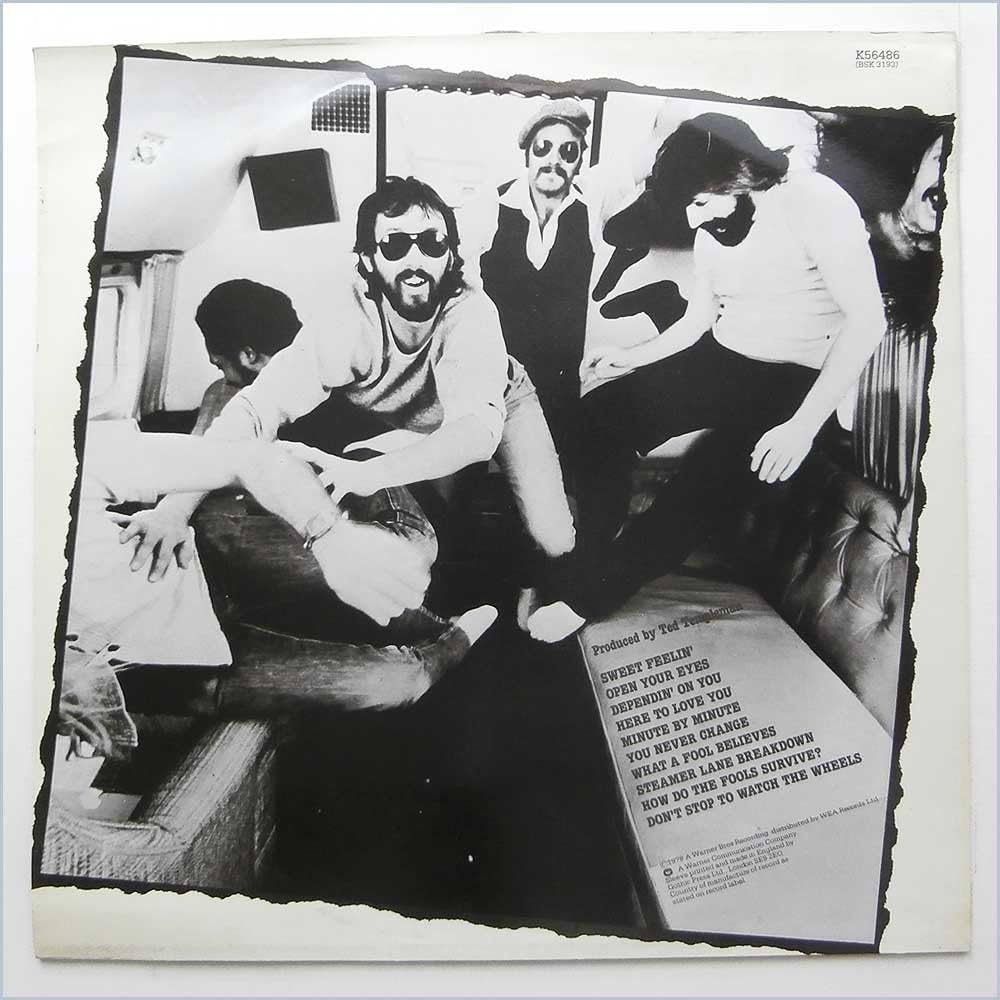

Your comfort level during the Doobieliner’s zero-gravity photo shoot

It started out really good on the Doobieliner and devolved into everybody turning green. The guy who was the photographer for the cover, on the eighth time the plane was dropping and giving us weightlessness, he turned literally green. I was looking at his face and watching him and thinking he was going to hurl. He started moaning and everything was floating. And I saw him start to regurgitate. And I thought, Man, if he blows chunks in the air, I’m going to be right behind him. One of the guys who was with us grabbed a plastic bag that had film in it. It all happened in the blink of an eye — he shook the film out and the canisters went floating into the air. He handed the bag to the photographer and the photographer threw up in the bag. He got it in. Thank you, Lord. I hope I can hold this down because that’s really disgusting. And that was the end of the photo shoot. We got all the photos needed, I guess.

The funny thing is you can hardly even tell what’s happening in the photo. There’s my foot or Keith’s foot floating up in the air. You can sort of tell there’s something going on there, but it’s not obvious that we’re weightless. But all of us were completely floating around the plane. It was a fantastic feeling to experience that loss of gravity. I was just happy to have a cover.

More From The superlative Series

“I kept saying, ‘What a Fool Believes.’ And they went, ‘Nah, that’s not the one.’”