After a flight to New York from my home in Tokyo last year, I stumbled across a professionally filmed microdrama that played out in bewildering, minute-or-two-long installments on my Instagram feed. Early in Money, Guns, and Merry Christmas, a defense-company CEO is asked by his date how much money he makes. As he says “Fifty or 60-,” she interrupts him: “Sixty grand — I cannot believe my daddy set me up with someone so poor.” We know the CEO was about to say “Fifty or 60 million” because he tells us this in a voice-over after his date declares, “Money is the only thing that matters,” and storms out of the restaurant. All of this happens before the end of one short reel, when a woman watching from the bar sets the plot in motion by telling the CEO that her father will cut her off if she doesn’t find a husband soon. He agrees to marry her on the spot, and over the holidays, her wealthy family heaps abuse on their new in-law, who they assume is poor and therefore worthless.

More than its plot or the fact that it was clearly filmed to be watched on a phone, it was the acting and dialogue of Money, Guns, and Merry Christmas that caught my attention — both very bad, but in ways I’d never seen before, like a community-theater production of a video-game cut scene. I must have lingered too long on the first post because the second installment soon showed up in my feed, quickly followed by the third and fourth. To my surprise, I watched each clip in full.

In China, similar smartphone-based parables of love and money are already a multibillion-dollar industry. During the pandemic, as viewers sought refuge in mobile entertainment, studio-produced microdramas began appearing in the sea of user-generated content on apps such as Kuaishou and Douyin, ByteDance’s Chinese version of TikTok. These “verticals,” as they are known, were so successful that by 2023, they were reportedly generating gross revenues of $5.2 billion, roughly equivalent to 70 percent of all theatrical movie-ticket sales in China.

Now, verticals are exploding in popularity in the U.S., even as mobile-first streaming remains associated with the spectacular failure of Quibi, the platform launched in 2020 by former Walt Disney Studios chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg, who spent more than $1 billion on a library of content, then shuttered the company after just six months. Those now succeeding where Katzenberg failed include Joey Jia, CEO of Crazy Maple Studio, which has produced more than a hundred verticals for users of its ReelShort mobile app. The problem with Quibi, Jia told me from his office in Sunnyvale, California, was that its ten-minute-long “quick bites” of content were too long, its production budgets too high, its actors too famous. “They wanted to bring Silicon Valley to Hollywood,” Jia said. “What we want is to reinvent Hollywood in Silicon Valley.”

Crazy Maple Studio is backed by the Beijing-based digital-content company COL and owned by Jia, who is a veteran of the Chinese telecom giant ZTE. Its success in the U.S. marketplace, Jia told me recently, is largely owed to a “feedback cycle” the company has managed to create through an ecosystem of mobile apps it has launched. The most important of these is My Fiction, advertised as an app that “brings the best voices in romantic fiction to your smartphone or mobile reading device.” My Fiction is both a self-publishing platform and a venue for reading what others have published, which also makes it a sort of online community. It has become a primary IP generator for Crazy Maple Studio, whose staff tracks the most-read stories on My Fiction in search of content that can be adapted into vertical scripts.

This helps account for both the stunning volume of verticals produced by Crazy Maple Studio as well as the sheer horny weirdness of titles like Selling My Virginity to the Mafia King or Claimed by the Alpha I Hate, the latter being one of numerous werewolf-romance verticals available on the ReelShort app. It also explains something that surprised me at first, which is that the biggest fandom for vertical microdramas on ReelShort, according to the company, is middle-aged and millennial women, as opposed to TikTok-obsessed Gen-Zers. This is something the company is working hard to change.

Never Underestimate Girl Math is one of ReelShort’s recent experiments in cultivating a younger, slightly less titillated audience. Its protagonist, Zosha Sanchez, is a teenager, and the plot focuses on her achievements and ambitions rather than a romantic relationship with some man (or werewolf).

Another apparent focus seems to capitalize on the Gen-Z and millennial fascination with tradwives. A startling number of verticals deal in various ways with contract marriages, especially those involving an age gap. One of these is Resisting Mr. Lloyd, in which Clarisse is “cut off by her evil family” and “needs money to stay in school,” while “rich CEO Austin Lloyd needs a wife.” Attempts to win more male viewers are equally revealing in the social and economic anxieties they speak to — in You Fired a Tech Genius, the protagonist is both fired and cuckolded by the boorish son of his boss, who has been tasked with dismissing an employee named Eric Martin while his father is away. The CEO’s son is warned not to accidentally fire Erik Martin, the company’s most valued AI developer, but he gets rid of the wrong man anyway. With all the gusto of a vaudevillian stooge, the CEO’s son spends the rest of the 68-minute-long movie ignoring mounting evidence of his error, until it bankrupts the company his father built. The hero is a stand-in, paradoxically, for both AI fanboys and those underappreciated tech workers whose jobs are imperiled by the technology.

There is no room for subtlety in a successful vertical. Because every 90-second clip needs to advance the story, heighten the melodrama, and summarize the plot for anyone just tuning in, the characters in these microdramas don’t bother with subtext. They say what they mean, or stroke their chin and look off into the distance while a voice-over tells us what they are thinking. Accordingly, the dialogue tends to sound as if it were written by veteran soap-opera writers who have been punched repeatedly in the head.

But because verticals are produced, optimized, and distributed for an audience whose tastes help shape them, sometimes even mid-production, they offer a distinct reflection of contemporary culture’s obsessions and taboos. To watch them is to experience the throbbing id of a post-cinema, post-television society, 90 seconds at a time.

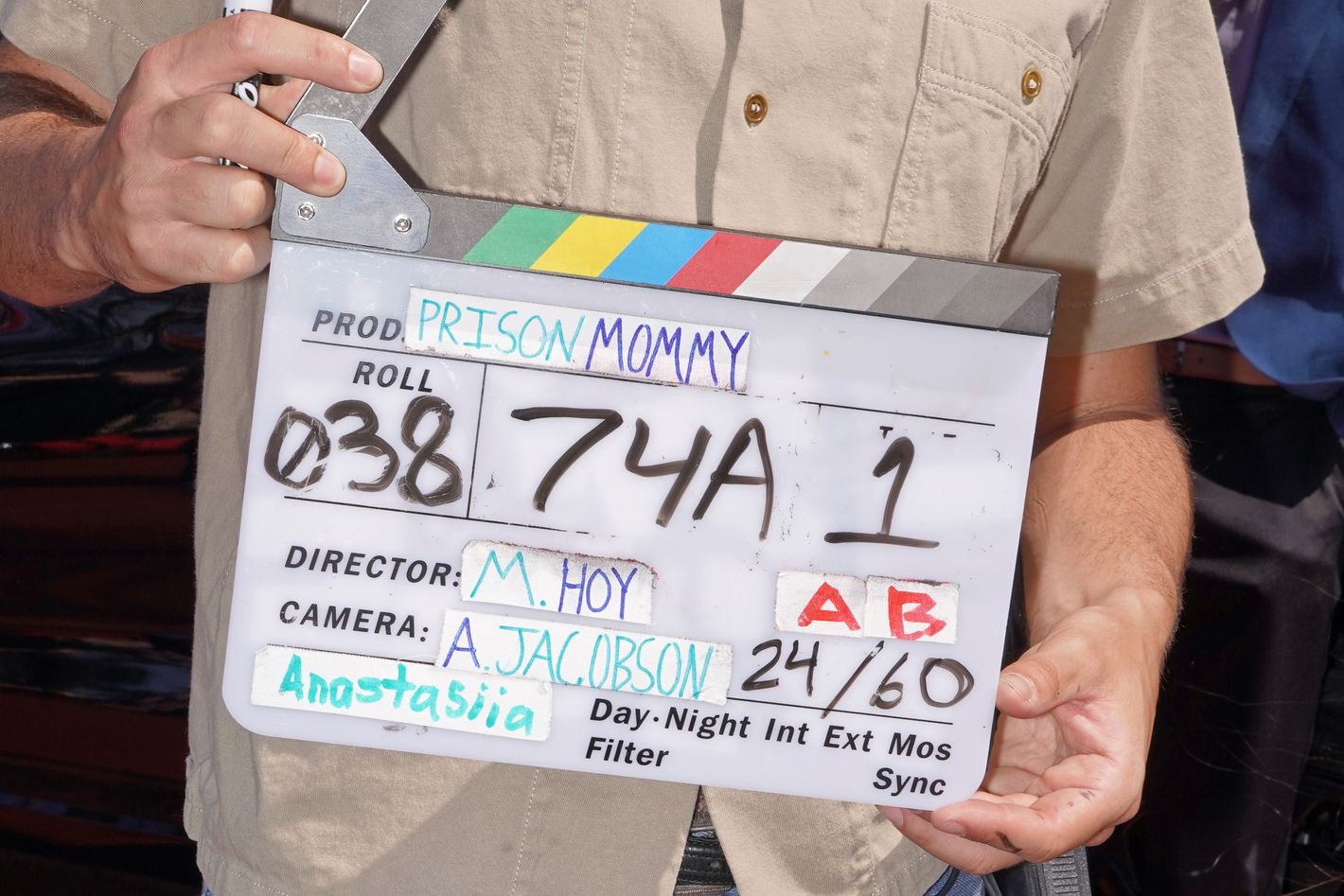

One hot afternoon in March, I met the director Cara Lawson on an improvised back lot nestled in the dusty canyons of Santa Clarita, California, where she was busy wrapping up an eight-day shoot. Her crew were mostly recent film-school graduates, young and fresh-faced, working on bare-bones sets built for a fraction of the movie’s budget, a mere $250,000. A single mobile home had to stand in for an entire trailer park where the protagonist lives with her hardworking single mother.

Many of the one-to-two-minute installments of microdramas like Never Underestimate Girl Math end on a cliffhanger, meaning the final product might feature as many as 70 or 80 micro plot twists. The first few episodes are free (with ads), but at some point, viewers will have to spend money to see more. According to Jia, the place in the story where a viewer hits a paywall is determined by the mass of data gleaned from 55 million active ReelShort users. When a promising concept fails, that same user data shows the company where viewers stopped watching. Sometimes the company will spend between $300,000 and $500,000 to reshoot underperforming movies, releasing what amounts to an anti-directors’ cut — an algorithm cut? — that aims to boost engagement. (A fair number of titles can also be streamed on social media and sites like Daily Motion.)

What ReelShort viewers are chasing seldom arrives until the final installments of the story, when the undercover billionaire or secret heiress discloses their true identity, then punishes their enemies and rewards that one person who believed in them all along. These moments can hardly be called reveals since they are often stated explicitly in the film’s title: There are no twist endings in Genius Baby Gets Daddy Back or Found a Homeless Billionaire Husband for Christmas, and in Never Underestimate Girl Math, the teenage protagonist does, in fact, prove that she is not to be underestimated. During my set visit, I mused with executive producer Bofan Zhang that the movie’s plot was a bit like Good Will Hunting in reverse; instead of being discovered, nurtured, and ultimately healed, Lawson’s working-class genius is tortured by a villain who takes credit for her work and taunted by clueless onlookers who, for some reason, doubt her facility with math. This Christlike journey of scapegoating and torment ends in comeuppance for the haters and doubters, whose petty provocations tend to evoke a Bond villain in adolescence. A few actors on the set of Never Underestimate Girl Math, for example, joked openly about how often these antagonists shout the phrase “How dare you!”

ReelShort verticals owe a profound debt to the made-for-television Lifetime and Hallmark movies in which women are variably terrorized and rescued by off-brand leading men who could, in the right light, pass for an A-list actor’s stunt double. But verticals are the work of outsiders: a parallel industry of recent film-school graduates, underemployed tradespeople, and creative laborers who have yet to meet the requirements for membership in Hollywood’s various powerful unions.

The rise of verticals in Hollywood was made possible by the one-two punch of production slumps brought on by the pandemic and then by the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes. This was explained to me by Lawson’s assistant director, Edoardo Novello, who moved to Los Angeles from Venice, Italy, four years ago to study film. By the time he could start looking for work on documentary and feature-film projects, the opportunities had evaporated.

“Everybody started doing verticals,” Novello told me, “because there was nothing else.” Even now, he said, as film and television work has picked up a bit more, verticals have remained an important source of quick income, the equivalent of Hollywood gig work.

When I visited the set of Never Underestimate Girl Math, one of my guides was Sammie Hao, who is the head of talent for Crazy Maple Studio. Since March 2022, when the studio started work on its first ReelShort vertical, it has been her job to oversee casting for every one of its productions. “Back then it was easy and hard at the same time,” Hao told me as we drove to the set in Santa Clarita. “Easy because it was during the union strike and a lot of actors were out of a job and looking.”

The hard part, Hao said, was that there was no dedicated pool of talent to draw from — no one had experience working in verticals because they were so new. It didn’t take long, however, to find actors through advertisements in trade publications like Backstage, whose casting calls, Hao told me, are now “80 percent verticals.” The relative lack of opportunities elsewhere in Hollywood means that enough mobile microdrama is being produced to cultivate a new class of talent that appears only in verticals. Some actors are even offered exclusive contracts, Hao told me, which suggests the rise of a quasi-studio system for verticals — one in which young women of color, like Hao and Zhang, are overwhelmingly represented in management.

Zhang, the executive producer, told me she is responsible for setting strategy for ReelShort’s entire in-house Los Angeles production slate. “It’s a lot of work, because I basically have to oversee six productions at the same time,” she said. Writing a script like Never Underestimate Girl Math typically takes a month, and the average shoot time is around eight days, after which an in-house postproduction team handles visual effects, sound, and color correction. Some projects get released just three or four months after a draft of the script lands on Zhang’s desk.

In March, I stopped by the studio’s L.A. offices to meet two of ReelShort’s biggest stars, who joined me for lunch in a common area facing a wall adorned with framed posters for films like Runaway Princess Bride and Surrender to My Professor. One of these microdrama heartthrobs was Marc Herrmann, a handsome leading man with a chiseled jawline and close-cropped hair. Before starring in ReelShort verticals including The Double Life of a Billionaire Heiress and Love Me, Bite Me, Herrmann was a rising star in the world of made-for-television movies. “When I showed up,” Hermann said of his first vertical experience, “I was like, This feels like one of those sets.”

This led to a bit of early friction between Herrmann and Robin Wang, the director of his first ReelShort project, who listened patiently to the actor’s copious script notes. “At some point he had to stop me, and he’s like, ‘All right, Marc, look: This is a vertical, and the stories are told in a certain way because it’s a vertical,’” Herrmann said. “‘We can try to push it toward being your traditional narrative, or a more normal story, and then it’s just going to live in this weird middle ground that doesn’t quite work.’ And when he said that to me, I had this epiphany, where I was like, Okay, I get it. It makes sense. This is a new thing.”

In the few years since his ReelShort debut, Hermann has become something like the Tom Cruise of verticals. He is treated not only as an actor but as a collaborator who can give input on scripts, and as ReelShort has grown more popular, he has even been empowered to help push its offerings into new genres. For Undercover Prison King, released in April, Herrmann worked with R. Ellis Frazier, a prolific director of action films such as Repeater and As Good As Dead. Some career television directors have also started to dip their toes into the world of verticals, Herrmann told me.

“It’s not just film students coming together to make these,” he said. “The whole industry is kind of crowding into this space because there’s stuff happening here at an especially slow time in the industry and people are loving it.”

We were joined for lunch by Adam Daniel, whose playful smirk and jet-black hair I recognized from Move Aside! I’m the Final Boss, in which he plays Kingsley Baldwin, “a wealthy corporate king” and “earth’s richest man,” who is for some reason dumped by his childhood sweetheart after returning from war. It was this vertical that left me wondering if I was seeing a confoundingly bad movie or some new medium altogether.

A vertical like You Fired a Tech Genius, strictly speaking, could be described as narrative drama. There are characters. Settings. Various plot elements. But instead of using images and sound to tell a story, or to draw the viewer into some other world, verticals are designed to deliver a steady drip of heightened emotion, strong and consistent enough to keep users watching until the end. Daniel, who starred in You Fired a Tech Genius, hinted at the emotional impact of the show when describing the flattering notes he received from tech workers. “People were so complimentary about showcasing that world and showing a character being masculine in that profession,” he told me. “Because apparently that was something they wanted to see more of.” Hao, the head of talent, suggested another emotional lure that may have helped the movie succeed. “It was layoff season,” Hao told me. “Especially in tech.” The fact that its viewership was 60 percent male, despite ReelShort’s overwhelmingly female audience, means the studio has started to home in on story lines that capture men’s fascination in the same way that it has so successfully mined content from the female-coded genres of fantasy and romance. Whatever data ReelShort gleans from audience response to You Fired a Tech Genius will invariably be used to fine-tune other male-coded verticals, which in turn will create more data-driven feedback.

The verticals pose an obvious, if unnerving, question: Are we too dumb, too tasteless, and too impatient to enjoy what once passed for popular entertainment? The answer, I think, has more to do with cinema culture than with internet culture — Hollywood, after all, is no longer a reliable generator of metaphors for our current condition, which auteurs like Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg used to diagnose through big-budget motion pictures. Now, the big screen is governed by gate-keepers who seem not only preoccupied with rehashing the themes of the comic book’s golden age but also oblivious to the way the internet has fractured and atomized people into niche audiences, which are seeing their interests reflected in ever more specific newsletters, podcasts, and TikToks. If the movies are a narrowing vestige of the monoculture, then ReelShort is the app that shows what’s flourishing in its stead: a million self-selecting microcultures.

“You read the comments on these Lifetime movies, and everyone is tearing them apart,” Herrmann told me. “‘The acting is horrible, the writing’s horrible,’ this and that, and you’re just like, Geez.” In contrast, he said, “you see a ReelShort project and the fans are so loving. Everyone is so supportive, they’re so kind, they love it. And there’s something nice about making something that people love.”

More From the Hollywood Issue

How a Chinese-backed soap-opera app is keeping L.A. actors employed.